When news of the Riot Grrrl Collection I was starting at New York University’s Fales Library hit the press, in 2009, I was unprepared for the amount of attention it would receive. Since then, I’ve done interviews, taught classes, written articles, worked with researchers, and edited a forthcoming book of ephemera from the collection. Throughout,I’ve tried to maintain the objectivity of a historian,the preservationist fervor of an old-school archivist, and the boosterism of a seasoned PR hack. I earnestly defend all of these attitudes as correct: I want this collection to convey the game-changing importance of this early-’90s teen-girl revolution as accurately as possible. But when the Believer asked me to choose items for reproduction and publication, my first though was: Yes! Finally! I can do whatever I want! And thus these selections are subjective. They aren’t representative of the bulk of the collection in any particular way. And my choices are partly motivated by aesthetics, despite the fact that I’m known for my endless exhortations that the content of Riot Grrrl zines, music, and fashion was indivisible from its subversive beauty.

Riot Grrrl emerged to provide an alternative to an ossified punk scene that increasingly supported the free expression of jaded straight white males at the expense of everyone else. Fostered in punk houses and dorm rooms in Oregon, Washington State, and Washington, D.C., this radical, anticapitalist, feminist movement’s primary forms of expression were zines, punk shows, and meetings. Zines were circulated at shows, shared with friends, or sent through the mail. Even when you mailed your zine to a girl three thousand miles away, there was usually an exchange of sorts—the gift was returned, whether in the form of another zine, a dollar bill, a stamp, or a new pen pal. I think this sharing-within-limits is what fostered the confessional style of many Riot Grrrl zines, which were like public/

private journals where it was safe to confess your fears or think through your oppression in real time. Other Riot Grrrl zines were filled with fervent rants calling for total revolution—but this, too, required the context of shared terms and common goals. When the mainstream press discovered Riot Grrrl—enticed by pictures of women in thrift-store dresses with Sharpie-marker messages repudiating sexism scrawled on their bodies—everything changed. Articles like Newsweek’s 1992 “Revolution, Girl Style” introduced a new cadre of teen girls to Riot Grrrl’s ideology and style, while the inner circle declared a media blackout.

It’s hard to remember a time when we thought we could control our message, and even harder to imagine an army of teenagers saying no! to free publicity. Now the things we create always have that small potential to (intentionally or accidentally) reach millions of strangers. The materials here are from a moment right before email, texting, and Twitter transformed everything.

The items I’ve selected relate to systems of exchange and circulation: meeting up, sharing ideas, trading goods. Sometimes they refer to the us-against-them mind-set of an underground scene scrambling to define itself while “alternative” aesthetics went mainstream. It was the intimate confines of a small subculture that made it possible for Kathleen Hanna to formulate a manifesto that called for us to “cry in public” and to “recognize empathy and vulnerability as positive forms of strength,” even while onstage with her band Bikini Kill she called for an angry-girl revolution. The form of the flyer speaks to this double life: it was designed to be folded into a small rectangle, functioning as either a tiny message you could privately pass to someone at a show, or a public flyer stapled to a bulletin board.

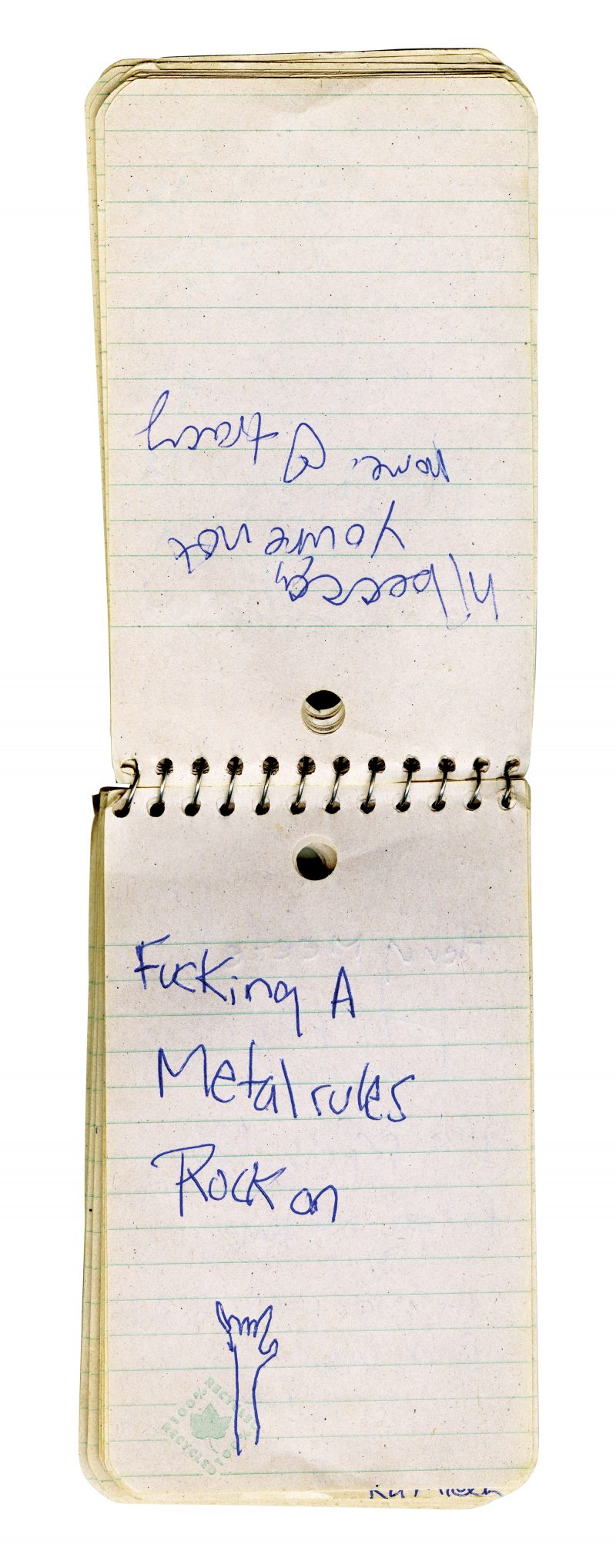

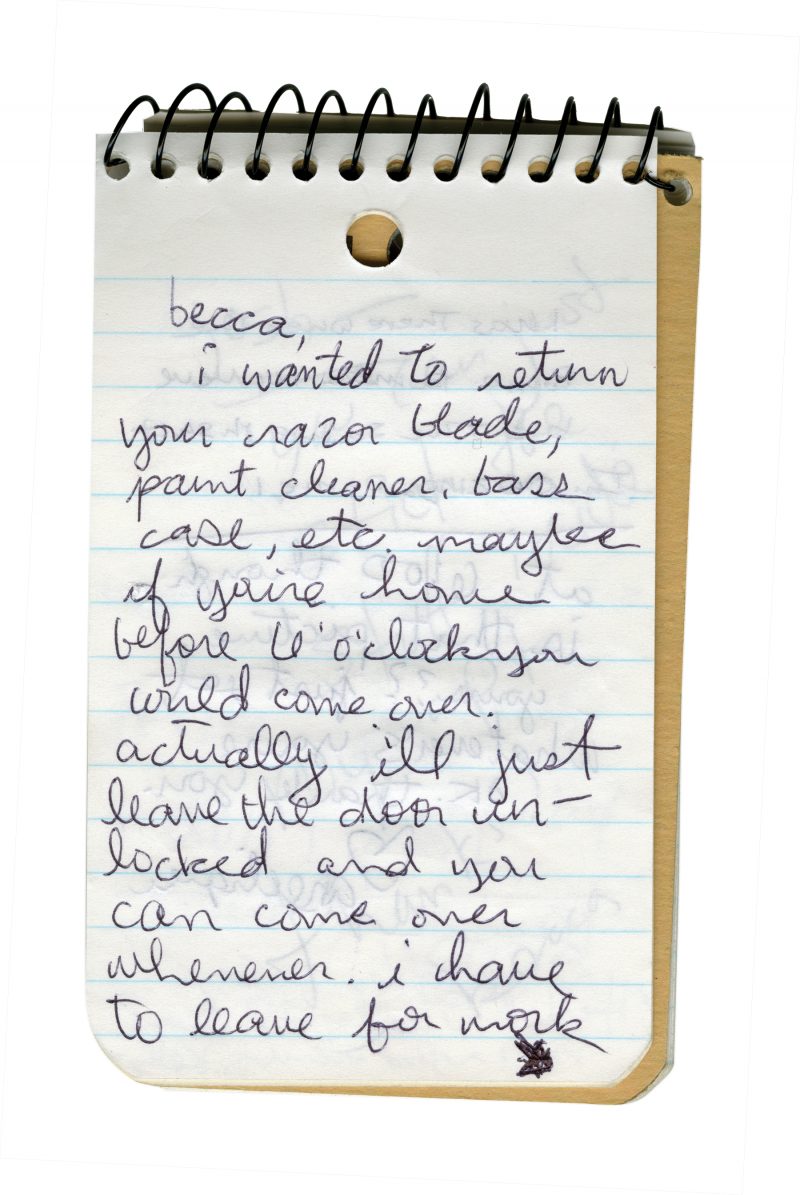

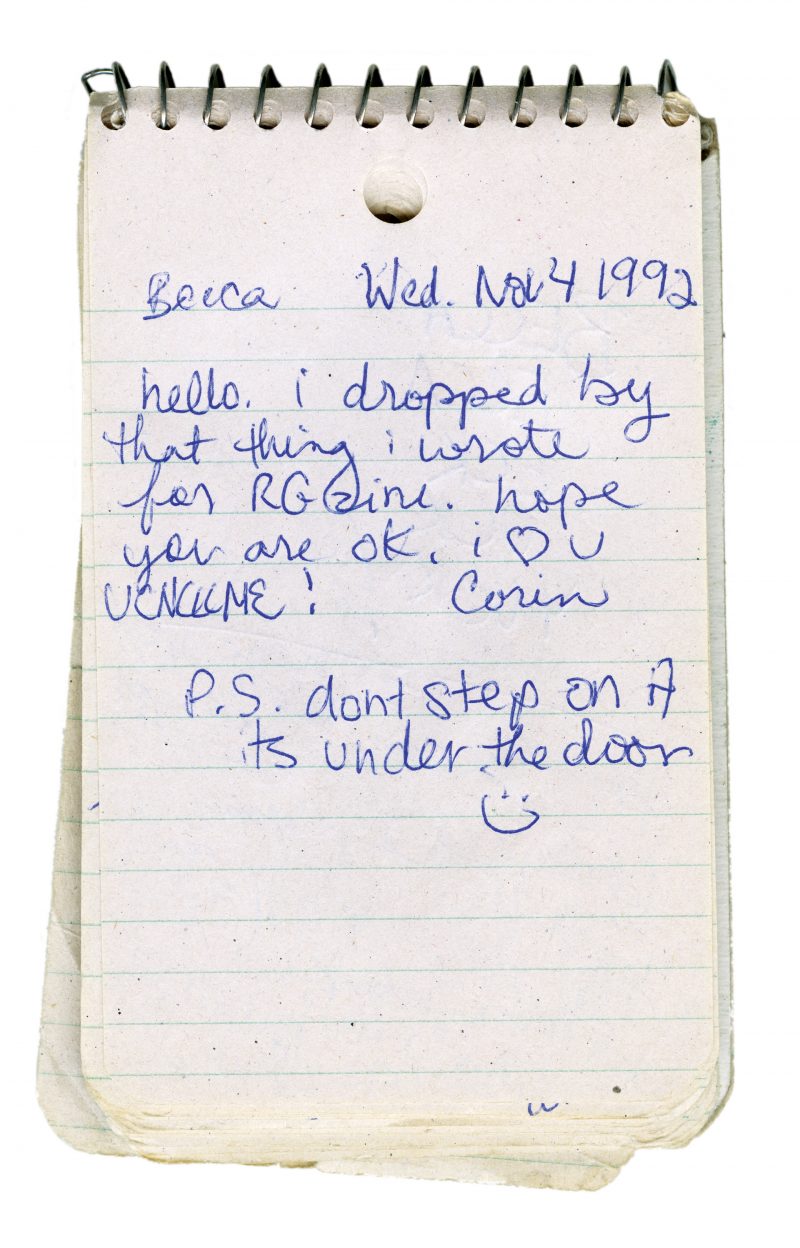

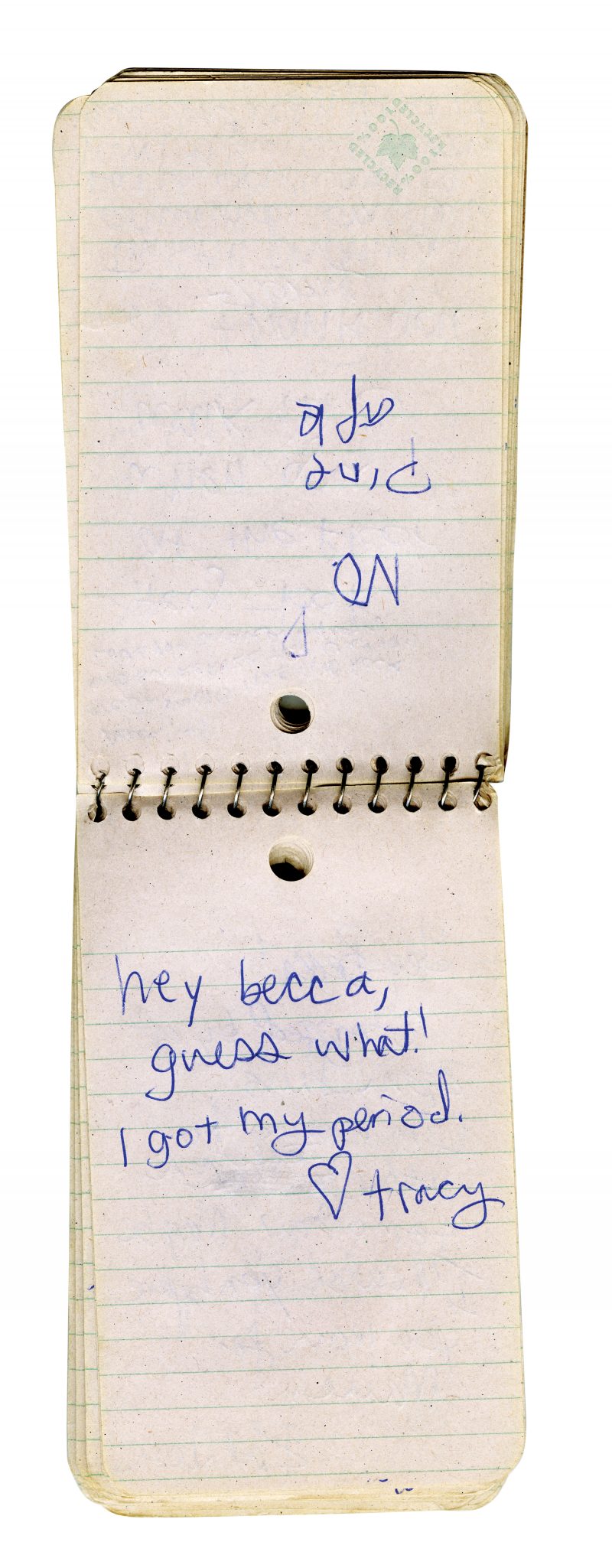

The eight small message notebooks in Becca Albee’s collection function in the same public/private way. Becca was an early member of Riot Grrrl, and played guitar and sang in the band Excuse 17 with Carrie Brownstein and CJ Phillips. In 1992, Becca moved to the Martin Apartments, home to many Riot Grrrls and other key players in Olympia’s punk scene, and kept the notebooks on her door until she moved out, in 1998. Most of the messages are along the order of “Hi Becca. I stopped by. You weren’t home.” Others are surprisingly intimate for something so publicly on view: “I’m a fuck up,” or “I got my period.” They are signed first-name-only, of course, and pretty much never dated, which makes their value as historical records somewhat dubious. But what I noticed as I read through them was how often they refer to small exchanges—requests to borrow a Band-Aid or a dustpan, an offer of soup or an herbal remedy. Olympia produced such a mind-blowing number of bands, artists, performers, and record labels in part because rent was cheap and resources were shared. Sharing requires trust, and trust requires boundaries. To someone on the outside, it might have looked like a clique; or, maybe, a radical attempt (borne of necessity) to live outside the system of monetary exchange.

The “insularity” of Riot Grrrl ended up being hotly debated within and without the movement. Both the media blackout and a “cool” culture of pretty (mostly white) girls in knee socks created a backlash of sorts, as poor kids, people of color, and queer kids spoke up about feeling excluded. A flyer calling for volunteers for a “Girl Convention” in Seattle demanded: “no hiding under safety blankets and privilege. Cos being safe=not having to recognize or take responsibility for yer/our own privilege and ways you/we oppress others.” Safe space engendered the Riot Grrrl movement, enabling many young women to talk openly about sexual violence and harassment for the first time, but maybe that space had become too safe.

To some, it may all seem very earnest. But throughout the Riot Grrrl Collection there’s an idealism that is often expressed through parody: most obviously in the use of collage and appropriation in zines and flyers, but also in quasi-ironic zine-homages to celebrities, and in parodic mod-stylings. Kathleen’s never-distributed 1996 Wheelie “Manifesto” might be a wry remake of the “Trust” flyer, a sort of allegorical turn away from the aforementioned confines of subculture—“all wheelies are different and beautiful”—but it also harkens back: “The kids know one need not destroy other wheelie gangs in order to enjoy themselves” isn’t so different from “Figure out how the idea of competition (winning and losing) fits into your intimate relationships.”

Ultimately, “The wheelie is ephemeral. It happens in but a moment and yet is beautiful, uncontainable, you never know when one might happen.” This gift is for you. You can take it or leave it.