Invention of an Erstwhile KGB Agent

The first drum machine, after a fashion, was the metronome. It was invented by Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel in 1812, and patented four years later by one Johann Nepomuk Mälzel. Evidently, the device caught on, especially after Beethoven made notation in a score for the metronome setting he favored. Salieri was also a fan. Soon metronome markings were common. Ostensibly, the purpose here was to torture poor music students, in order to rid them of their listing and surging rhythms. Faster when excited, slower when pondering the meaning of a particular passage. And yet eminent composers began complaining of “metronomic regularity” soon enough. (“I do not mean to say that it is necessary to imitate the mathematical regularity of the metronome, which would give the music thus executed an icy frigidity; I even doubt whether it would be possible to maintain this rigid uniformity for more than a few bars.”—Hector Berlioz)

Still, the metronome, in one form or another, achieved market dominance and held it for a very long time. True, for the purpose of a music lesson, the ticking of the metronome could be anywhere you wanted it to be in the time signature. For example, if the piece in question were a waltz, you could set the metronome for ninety, and then imagine that the TICK of the metronome were in the middle of the measure—beat, TICK, beat—or at the beginning—TICK, beat, beat, which would be a rather traditional waltz—or even at the end—beat, beat, TICK. The same was true whether the piece was in threes, fours, or fives, or nines, as long as its measures were evenly subdivided. This was plenty of rhythm, this was a versatile rhythm, even if unsophisticated.

Still, in the course of music history, when music runs into an implacable and immobile musical truth, such as the truth which holds that the metronome has its limitations, then music history has no choice but to call out for someone like Leon Theremin.

Leon Theremin, the late, great inventor of the radio-wave playback device known by his surname, the musical instrument that launched the electronica revolution, the instrument that made his wife, Clara Rockmore, one of the foremost classical-music interpreters of her time (and if you have never heard her renditions of the classics on the theremin, you owe it to yourself), Leon Theremin, erstwhile KGB agent, was also a designer of a drum machine, perhaps the first drum machine that was ever to have any great impact.

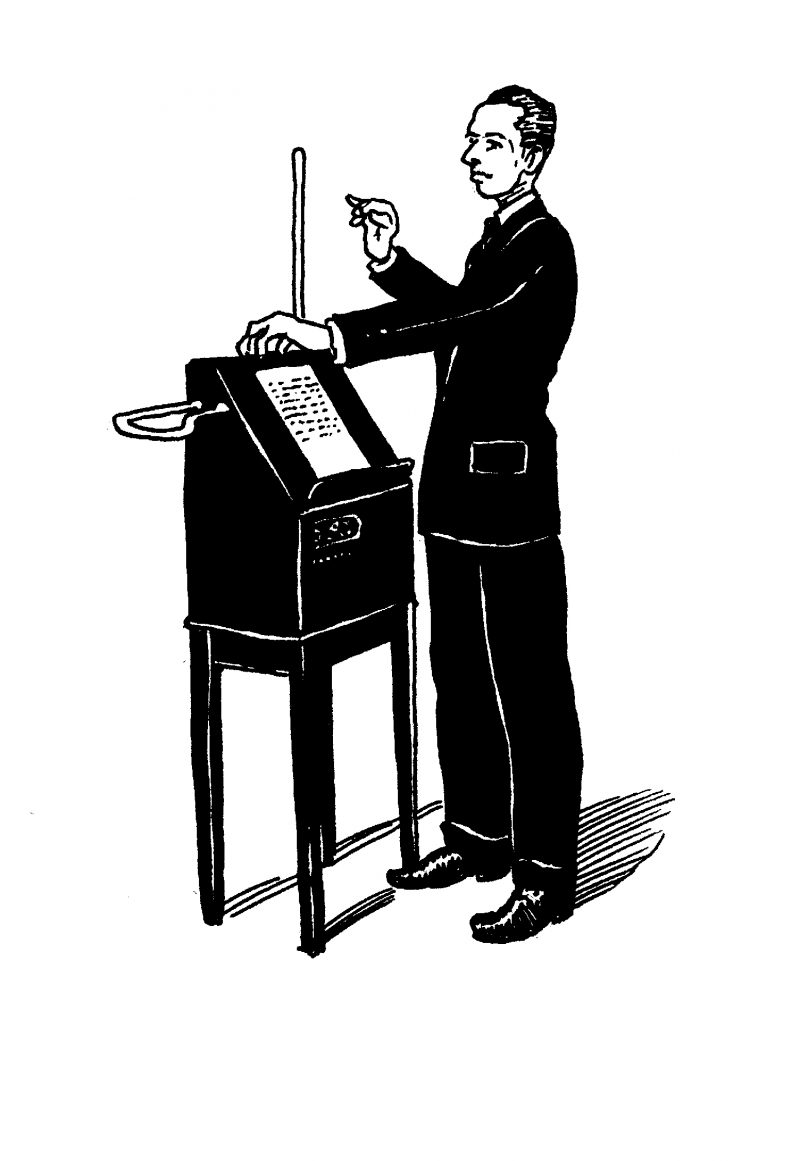

The request for the Rhythmicon, as the percussion device was to be known, came in 1930 from the American composer Henry Cowell, who, according to later versions of the tale, felt that his microtonal and polyrhythmic compositions needed some kind of percussive accompaniment that was as yet unavailable in this world. Which was another way of saying, as is often the case in this story, that the drummers of the time were simply not up to the task. Theremin’s Rhythmicon, of which only three were built (the one built for Cowell was rather quickly abandoned), had sixteen keys, each featuring a different rhythm based on a different note. Two keys could, of course, be played together, so that you would get the cross-rhythmical purposes of the different rhythms. After Theremin’s rhythm generator failed to take off with the same renown that greeted the inventor’s theremin, the drum machine, as an idea, failed to find a new champion for about fifteen years, until Harry Chamberlin invented his Rhythmate (in 1947), which used actual tape recordings of an actual jazz drummer (there wasn’t really rock and roll yet), and made possible the playback of these recordings, up to fourteen at once. This design was somewhat along the same lines as the Mellotron (which became the orchestral tool of preference for the progressive-rock bands of the middle and late ’60s).

It’s not surprising that some of these early drum machines were packaged for the electric organ, which was the electronic keyboard of its time, among these the Wurlitzer, which shipped, for a while (much like the Casio, later), with a rhythm generator called a Sideman, in the late 1950s. As with the Chamberlin and the Rhythmicon, the Sideman played very specific rhythmical patterns, the cha-cha, the tango, the foxtrot. Nothing, in these early days, could be better than obtaining a mechanized drummer who would play a very specific dance beat (though owners of the early Casiotones will testify as to how quickly these beats can drive you insane).

The next inventor to get involved on the design side of the problem was Raymond Scott. Scott, who in the ’40s was a writer of “jazz” tunes (you can sort of see the contradiction here right away: Scott “wrote” jazz tunes, which is to say he through-composed them, though jazz, theoretically, was semi- or entirely improvised), among these the famous “Powerhouse,” which became a standby for Carl Stalling, who reused its theme again and again for the Looney Tunes sound tracks. However, by the early ’60s, Raymond Scott had turned his attention elsewhere, to early electronic music, some of it produced for advertising. His Soothing Sounds for Baby: An Infant’s Friend in Sound series of album releases from 1964 were lullabies, or ostensible lullabies, created for babies of specific ages, and for these recordings Scott devised first his Rhythm Synthesizer, and, later, the more covert Bandito the Bongo Artist (circa 1963). A good example of this sort of a sound can be found on volume one of the Soothing Sounds series, on the song called “Tic Toc,” a metronomic piece for unaccompanied Rhythm Synthesizer.

There’s a problem with a piece like “Tic Toc,” however, as indicated by my friends who have attempted to play “Tic Toc,” and, indeed, other compositions from Scott’s series, for their children. One friend, when I told her that I had purchased a volume upon the re-release of these Scott compositions, was bluntly open about the difficulty: “Kids hate that stuff.”

Why this reaction to Soothing Sounds for Baby: An Infant’s Friend in Sound? On its most superficial basis, the whole of the recording is not terribly different from the tinkling of music boxes. There is a judicious use of echo throughout. There are, on many of the compositions, melodic bits to chew on. (“Tic Toc,” it should be said, has none of these virtues.) Nevertheless, I would contend the absolute lack of variation in rhythmic patterns can, and will, needle baby because baby, perhaps like his or her parents, cannot and does not thrive when the rhythmical construction is not more organic.

The middle ’60s found a crowded field in the development of drum machines and rhythmical synthesis. On the whole, these rhythm generators from the ’60s were analog re-creations of drum sounds, most of them made with oscillators, the primitive versions of synthesizers, which were also beginning to be employed melodically elsewhere (in Raymond Scott’s work, for example, or in Wendy Carlos’s Switched-On Bach). Because the timbre of these synthesized drums didn’t sound very much like drums at all, the resulting sounds are, in their way, somewhat beautiful, and, insofar as they have dated now, they have grown only more ephemerally lovely in their old-world homeliness.

When the great period of pop-music experimentation collided with the drum machine, which is to say the period between 1968 and 1974—the pre-punk period of pop-music modernism—people began to do some interesting things with these technologies. It turned out there were two rather interesting ends of the spectrum available to the discerning listener in 1971. The synthesizer had already been used in popular music by 1971, by the Beatles (on Abbey Road), by the Monkees, by the Mothers of Invention, by some of the prog-rock pioneers (Rick Wakeman, Keith Emerson). But the drum machine didn’t really begin to get its showcase until the early ’70s. There were two divergent examples, as I say. One was rather unlikely: the soul-music masterpiece of Sly and the Family Stone, There’s a Riot Goin’ On. Listen, if you will, to “Family Affair.” The groove is beautiful, the melody is beguiling, Sly’s voice, which kind of purrs, going in and out of the baritone, is incredibly expressive, but what is making that rather strange percussive sound that seems to be coexisting with some live drumming? The drum machine.

The other example from 1971 couldn’t be further afield. It’s to be found on Tago Mago, the wild, improvised, noisy, improbable album from the German experimental-music pioneers Can. The particular track to showcase the drum machine, “Peking O,” is long, quixotic, glued-together in that sort of Karlheinz Stockhausen way that Can favored (indeed, one of their members studied with Stockhausen), and has plenty of acoustic drumming, alongside its rather wild and irregular drum-machine passages.

Can also had one of the very greatest drummers in rock-and-roll history, Jaki Liebezeit. His style, which left so much room in the groove, so that the bass and rhythm guitars might find their way in and out of the beat, had enough jazz in it to avoid sounding, well, metronomic. And, in fact, “Peking O” managed to use the drum machine without allowing it to dominate the rhythm at all. This sophisticated application is not unlike Can’s sophistication with electronic timbres in general. Can were nothing if not experimenters.

Therefore: in the early ’70s, there were two ways to use a drum machine, the African American way and the German way. It seems clear to me that in Sly Stone the drum machine is part of an ongoing search for the perfect rhythm section. The players in the Motown orchestra, not to mention in James Brown’s band, or in Parliament-Funkadelic, were capable of such inventiveness that it was, arguably, impossible to do better, to be as supple, as creative, as rhythmically dextrous. Sly Stone seemed to have decided, therefore, that the only way to play any tighter than James Jamerson and Uriel Jones was to be a machine.

The Edge of German Perfection

Let it be said that I understand the concept of preferring robots to humans, and I admire the honesty of people who claim they prefer robots to humans, but, in the long run, I do not believe a unilateral robot preference. When Kraftwerk says that they want to be robots, or that they constitute a man-machine symbiosis, what I really think they are saying is that they are incapable of working with actual human drummers.

The initial Kraftwerk, the repressed Kraftwerk, the band before its breakthrough of monotony, Autobahn, made four albums: Tone Float, Kraftwerk I, Kraftwerk II, and Ralf und Florian. These albums, which reflect the origins of the two composers of the band (Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider) in German experimental music (Stockhausen, especially) are interesting, and, in the case of Ralf und Florian, singular, even strange. Among the uncharacteristic features of early Kraftwerk was Florian Schneider’s interest in Hawaiian steel guitar, much present on the comical and heartwarming (it’s almost a lullaby) “Ananas Symphonie,” which manages to transcend the preset rhythm generator that appears on it. He (Florian) also played a fair amount of flute on these recordings, which is about as twee as you can get and still be a part of the rock-and-roll orchestra.

Kraftwerk also employed, in this early period, a sequence of drummers, most notably Klaus Dinger, who, with Michael Rother, then left Kraftwerk to form Neu!, the Krautrock band that exerted a significant influence on punk. Dinger’s style, the so-called motorik drumming style, was noted, like Jaki Liebezeit’s, for its simplicity and its absence of fills. Dinger did not hold the Kraftwerk drumming chair for long, though he played like a metronome, and that goes for all the other early Kraftwerk drummers, too. If one were attempting to make a comparison between motorik and the “metronomic regularity” of Kraftwerk’s later canned and sequenced electronic rhythms, you might suggest that German popular music generally seems to favor its totally stripped-down beats, its clean rhythms, its manufactured and repetitive drum parts. But there is a difference between motorik and drum machines. Kraftwerk wanted the drummers to accept the limitations imposed on them, and for this reason they were unpopular with percussionists. As Ralf Hütter himself admitted, “Not only were we interested in Musique Concrete but also in playing organ tone clusters and flute feedback sounds that added variety to the repeated note sequences that we recorded and mixed on tape. Then we used several acoustic drummers as we turned our attention to more rhythmic music, and soon found that amplifying drums with contact mics was desirable for us but not readily accepted by the players.” Karl Bartos, who with Wolfgang Flür was one of the “drummers” during the high period of Kraftwerk’s music, admitted to finding the job somewhat tedious, according to Pascal Bussy’s Kraftwerk: Man, Machine and Music: “There were no offbeats, and if I played offbeats they were rather disturbed by it.”

Flür, who joined on drums in 1973 in order to facilitate a television appearance by Kraftwerk, remarks in his own autobiography that he followed a string of drummers who didn’t work out: Hütter and Schneider “told me about their appearances with Thomas Lohmann, a jazz drummer who was well known at that time, and how, after him, they made an attempt to get on with Klaus Dinger. This must have been a trial for them because both drummers had strong personalities and both regarded their drums as solo instruments.”

At the same time the band had begun assuming the depersonalized guise of robots. I imagine that Kraftwerk is, in part, intended to be a comedy act, and that all Kraftwerk albums are meant, to varying degrees, to be ironic. (See, for example, “Computer Love,” and similar compositions.) But it is also apparent that the cyborg theme begins to rear its head (“Showroom Dummies,” on Trans Europe Express) at about the same time that the drummers become unnecessary to the band. “We are standing here / Exposing ourselves / We are showroom dummies / We are showroom dummies.” While musicologists and cultural critics may try to create an argument whereby the doggedly moronic qualities of Kraftwerk lyrics are clever and forward thinking, a sly compositional strategy somehow related to the Ramones (“Beat on the brat / Beat on the brat / Beat on the brat with a baseball bat / Oh yeah, oh yeah, oh yeah”), I feel that it’s more likely that “Showroom Dummies” is the beginning of Kraftwerk’s sense of alienation from the writing/recording/touring obligations of life as a successful musical act in the late ’70s.

Thus, the band built actual robots that cavorted at their gigs because it was funny. (Flür: “We found some standard clothes for our robots, which had wooden ball-and-socket joints at their shoulders, elbows, and knees to allow them to be bent into position.… Now all we had to do was buy red shirts, black trousers, and shoes for them.”) Before long, Ralf Hütter even spoke of a halcyon future in which he could have his robot do his interviews for him, saying that the robot would know all the answers. And yet a trial run along these lines didn’t go so well in Paris, according to Flür: “The press had been thoroughly unimpressed, and had pulled our dummies apart over the course of the evening.”

The joke was taken quite a bit further beginning on The Man-Machine (1978). And the relevant song from that album is “The Robots”: “We’re functioning automatic / And we are dancing mechanic / We are the robots / We are the robots / We are the robots / We are the robots,” after which the vocoder enters with a Russian-language passage: “Ja twoj sluga [I am your slave], / ja twoj rabotnik [I am your worker].”

The album in question also had a song at the end designed to summarize the relevant philosophical concept, called “The Man-Machine.” There, the will-to-cybernetics lyric goes thus: “Man-Machine, pseudo human being / Man-Machine, super human being.”

What are the distinctive features of the Kraftwerk robots, as we understand them according to these lyrical iterations? The robots seem to function, it would seem, like fembots, or like sex slaves; that is, they offer pleasure without emotional consequences; additionally, the robots represent both a comical reduction of humanity (“pseudo human being”) and Nietzschean evolutionary triumph (“super human being”). The music on the album likewise reflects a transition, becoming less experimental (as had been the case since Trans Europe Express) and, therefore, less unpredictable. The Man-Machine is a pop-music confection, a mechanized, sequenced, and streamlined sound, in which all the unpredictability has been left out. The jacket of The Man-Machine, meanwhile, was controversial in that the design, which mimicked Russian constructivist El Lissitzky, featured the four members of the band wearing identical red shirts and black ties. Hard not to find a bit of totalitarianism lurking in the imagery, and, indeed, the perfection of German culture, even when parodistically applied, does summon such a thing. The immediate postwar generation of German young people always faced this choice. One result of the struggle is what you get in W.G. Sebald, a recoiling from fascism, a constant wrestling with the legacy. The other result is to constantly play with the edge of German perfection. As Flür has it in I Was a Robot,

We had no adult role models from whom we could learn to take pride in our own culture. How could we comfortably feel German in a country where there had been book burning, banned pictures, ruinous film criticism and “degenerate art” a short time ago? A time when many of our German poets, painters, composers, actors, and the most ingenious engineers and inventors had been driven from the country and fled into exile?

Maybe the drum machines, in this circumstance, had become a necessity, or a natural outgrowth of a music that, whether or not for comic effect, refuses to engage with humanism, whether in order to comment on native German culture or in order to call attention to the rigidities in German politics. Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider, in the end, wanted to disaffect themselves completely, in the context of Kraftwerk, and to make themselves fit only for parody. As if to say something about the choices left to them in the cultural moment?

There was one more good album, Computer World (1981), the title of which no longer feels futuristic at all; in fact, it sounds like the name of a technology magazine with a diminishing number of ad pages. I confess I really liked this album when it came out, and I still do kind of like it. I also like Trans Europe Express a lot. I confess, and it is an unavoidable confession, that Kraftwerk wrote very good melodies, and when they bothered to excel at writing melodies, they stood for something musical. It is no coincidence that they constantly refer to the Beach Boys and the Ramones as fellow travelers and influences. Both bands, though aesthetically far from the “metronomic regularity” of Krautrock, were great melody writers, great evokers of place and time. Kraftwerk, in their musical compositions, which is to say in their melodic composition, and their minimal chord voicings, clearly do have a great gift for popularizing and for writing the catchy hook. They reached their apex on Computer World.

“What music isn’t experimental?” Hütter once reportedly asked of Brian Eno, apparently trying to rationalize their more commercial output. Indeed, any time you record a track, you are trying something new, even if in doing so you are doing it exactly the same way you did it before. Historical repetition is not as easy as it would seem. But still. After The Man-Machine, Kraftwerk’s output is more concerned with technological innovation than with musical innovation. The songs, after a point, sound identical, and the same is true of the lyrics, with their campy celebration of gadgetry. What changes is the synthesizer technologies, and, to some extent, the timbre of the drum machines.

Which means that this music dates very, very quickly. In fact, Kraftwerk, in lieu of releasing a greatest-hits package, did release a remix package in 1991 called The Mix that tinkered with the classics of the band by attempting to update the drum sounds. By then, however, there was nothing more to say. Ralf Hütter’s obsession with cycling gave the band one new track in 1983, “Tour de France,” which they then tricked up with some samplers and digital geegaws for 2003’s Tour de France Soundtracks.

In the late ’70s, Kraftwerk were influential, in that they spawned a great number of imitators (of which more below), but both Kraftwerk and the imitators sound, these days, about as futuristic as “Popcorn” by Hot Butter. Kraftwerk have toured recently, but what does it mean for Kraftwerk to make live music in the twenty-first century? Apparently it means that everyone in the early versions of the band is retired or forced out except Ralf Hütter (who is accompanied by some lighting designers and video designers who stand onstage manipulating pre-recorded tracks with their laptops). It also means that they are not going to play anything substantial that was written after 1981, or, at the time I write these lines, twenty-eight years ago. I for one would rather stay home. Which is apparently what Florian Schneider now does, too.

A Gospel Band Pretending to be a Rock-and-Roll Band Pretending to be a Synth-Pop Band

There has been some really great German electronic music made in the last twenty years. I’m thinking of Oval, Microstoria, and Mouse on Mars (the last of whom eventually collaborated with former Kraftwerk “drummer” Wolfgang Flür), bands who solved the problem of “metronomic regularity” and the shame of German rhythmic perfection by (in the case of Oval, e.g.) avoiding drums and rhythm entirely (much of Oval’s music was composed by using skipping CDs), or, in the case of Mouse on Mars, by affecting a very comical warmth that depends on reggae, bossa nova, surf, tango, and other disgraced and somewhat effusive music.

The first bands that slavishly followed Kraftwerk, that drank deep of their Apollonian linearity, had none of this comedy and warmth. They not only took the electronic surface from Kraftwerk, but they took, if you like, all the will-to-power imagery; they took the dehumanized thematic material of The Man-Machine and Computer World and fused it with some of the recessionary post-Christian, secular gloom that, while it can undergird German culture, never found there a host body as perfect as in England. The synthetic bands of the early ’80s, the primarily British synthetic bands, missed the irony and paradox in Kraftwerk, and they embraced the despond and numbness of electronica as though this was the affect of the times. Whereas punk, played primarily on guitars, made and felt fury in order to empower (politically and emotionally), synthesized post-punk—in bands like Ultravox, Visage, Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, Magazine, the Human League, Heaven 17, Blancmange, Soft Cell, and so on—was about disengagement and anhedonia. Many of these bands (with some notable exceptions, including Gary Numan and the later OMD) used drum machines, as if the absence of a drummer, and with it the absence of the Dionysian joy of great drumming, were somehow essential to the dehumanized and slightly sophomoric dejection sketched out in this work.

And from out of the tortured depths of British electro-pop of the early ’80s came, arguably, the preeminent exemplars of the form, at least in this first incarnation, Depeche Mode. They are unlikely musical heroes, for the simple reason that they have, twice over, off-loaded the best musicians in the band along the way. And yet they have endured. They were founded in 1980 in Basildon, which is about twenty-five miles east of London, just far enough away to be out of town, which is to say parochial, which is to say confined to the borders of the parish, and initially they were formed from the comingling of a pair of bands that featured old-fashioned guitars, and even drums. Two of the members of the resulting collective, keyboardist and songwriter Vince Clarke and singer David Gahan, were poorer, solidly working-class, and therefore more driven by need and circumstance. The two other members, Martin Gore and Andy Fletcher, had proper jobs. Gore, in fact, worked in banking. These two were considered the less-gifted members, and Fletcher, in fact, played an instrument, the electric bass, that was quickly eliminated from the ensemble upon its movement into the synthetic realm.

What did it mean to go electronic? In part it meant that you were under the sway of Kraftwerk. It also meant that you couldn’t afford a drummer or a rehearsal space, things that had probably been easier in an earlier period of rock and roll that didn’t require walls of amplifiers and mixing boards and expensive electrical gadgets. Indeed, Depeche Mode, in their early rehearsals, played with headphones on, so as to avoid bothering the neighbors. Of the decision to eschew a drummer, David Gahan said, “I know Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark were put down for using a drum machine onstage but the worst thing they ever did was to get a drummer. It was really bad after that. We don’t need one anyway—it’s just another person to pay.”

The first Depeche Mode album, Speak and Spell, was a huge success for a band still only in their late teens and early twenties, and the compositions, while mostly rudimentary (especially with thirty years’ hindsight), have a tunefulness, even a cheerfulness, notably absent from the later work. That is probably because the chief writer, Vince Clarke, soon to quit the band, wrote the songs, and, though much alienated from this somewhat alienated band, he prevented goth moping, under his reign, from rising to the surface. “Just Can’t Get Enough,” the best-known song from the album, is cut-rate Motown fluff, as singable and as cheery. This album has nothing to do with the Kraftwerk part of this account, and that is perhaps why Vince Clarke had to go, and why Depeche Mode had to turn in a much different direction in order to achieve its infamy.

This different direction runs from the second album, A Broken Frame, released in 1982, up to Violator, from 1990, a span of six studio albums, and it includes some of the most popular “alternative rock” songs of the period, on the basis of which many wildly excessive epithets have been affixed to the Depeche Mode legacy. The thematic material of most of this work is somewhat superficially dark, somewhat brooding, and obsessed with sex, in particular sadomasochism, or at least a sadomasochism as imagined by a seventeen-year-old from the suburbs, or, later, a twenty-five-year-old, and this is how the band got a reputation, despite its squeaky-clean synthesizer parts, its drum machines, and its lack of sexiness, for being goth.

By 1988 Depeche Mode was headlining in Pasadena, at the Rose Bowl, in front of seventy thousand people, a feat preserved by D. A. Pennebaker in the film 101. Pennebaker apparently knew nothing about Depeche Mode before he contracted to make the documentary, but he says he wasn’t really interested in Bob Dylan’s work before Don’t Look Back, either. A great portion of the material is played by samplers and MIDI keyboards without undue input by the musicians, excepting Alan Wilder and Martin Gore. Gore just seems to stand there, and since Fletcher contributes nothing, and Wilder has to cue the machines, that leaves David Gahan, the lead singer, to do most of the work with respect to the audience, which he is not entirely capable of doing, despite a great deal of hortatory shouting—and no wonder he fell into the chasm of addiction in the ’90s for a good long spell (and this is why the significant period of Depeche Mode ends with Violator, during whose tour Gahan apparently began his free fall and not long after which Wilder quit).

Was it the times? Did the ’80s just make tinny, irritating superficiality inevitable? Along with digital reverb? Did anyone think to avoid putting digital reverb on their drum tracks? Could Kajagoogoo or Wang Chung have come from any other time in history? Even people who should have known better, like the members of New Order, fell prey to the allure of the drum machine and the sequencer, and the fashionable anomie of the dance-inflected, fully programmable pop song. It was like a virus sweeping the British countryside.

But my argument is that the drum machines dictated the material, not vice versa. Once you have the drum machines, the material inevitably tends toward “Master and Servant,” or “Blue Monday,” or “Tainted Love,” or “Sweet Dreams Are Made of This,” and this is in part because after Kraftwerk, and the robotics that had been brought into being through their work and fused with their drum machines, you had a thematic tendency, a theme that made the most out of the inflexibility, the rigidity, of the beats, and that rigidity made for an unfeeling surface, which in turn led to songs about an absence of feeling. There is no moment of joy in a Depeche Mode performance, when the players are swept up in Dionysian celebration, and there is no surprise in the compositions, because they are played the same way every night, and it’s no wonder that Martin Gore, despite having written the songs, looks bored or depressed while playing them.

The nihilism of this approach also implies, in due course, another inevitable subject, at least in Britain, and that is European secularism. British atheism is part of this storied tradition. It’s so fervent that it seems, on occasion, indistinguishable from the Church of England itself.

And thus, in England, the history of drum machines, and of rhythmic organization, is conjoined to a Nietzschean feeling of neglect by God, and this comes up again and again in the Depeche Mode story, since nearly every one of the original members was a churchgoing kid, and some of them even met there. Gahan “had a religious upbringing thanks to his mother’s side of the family, who were involved in the Salvation Army.” And Martin Gore’s extensive trail of comments on churchgoing includes the following: “I was going… a lot [as a child], not because I believed in it, but because there was nothing else to do on a Sunday.” Andy Fletcher was also a regular church attendant, to the point of going, in childhood, “seven nights a week,” and Vince Clarke, according to Fletcher himself, was the same: “He was a real bible basher.”

If much of the British synthetic pop of the ’80s has Anglican atheism serving as its structuring absence, in addition to a lite version of the existentialism of Nietzsche, then why is Martin Gore so preoccupied with God later on? As in the following from a mid-career interview: “I do believe in some sort of power even though I haven’t really had any experience myself. I’m still searching. I really like the idea of belief but I’ve never found anything to believe in.” Or even later: “I wake up every day and I see sunshine and I see amazing mountain views and I do feel a little more in touch with God, whatever God is.” Thus it appears: Depeche Mode loved their perfect beats, they loved their psychosexual darkness, but they were also preoccupied with spiritual questions.

Which is why I want to talk about a few songs in the Depeche Mode canon that seem to violate the Nietzschean anti-Christian tradition, asserting instead a kind of engaged spirituality that has grown ever more sustained. The more middle-aged these synthetic goth avatars have become, the more mortal, the more human they appear. They are, on the basis of the songs below, a gospel band: a gospel band pretending to be a rock-and-roll band pretending to be a synth-pop band. It becomes truer with each passing year.

The first song I want to examine is “Blasphemous Rumours,” from Some Great Reward (1984). “Girl of sixteen / Whole life ahead of her / Slashed her wrists / Bored with life / Didn’t succeed / Thank the lord / For small mercies / Fighting back the tears / Mother reads the note again / Sixteen candles burn in her mind / She takes the blame / She goes down on her knees and prays.” That’s verse one. If the song at this point is meant to be “blasphemous,” it manifests a very gentle blasphemy, confining itself, in fact, to a sorrow that the story as described exists, that the girl slashed her wrists, that this Depeche Mode audience member, for such are the implications, tried to kill herself; or perhaps the blasphemy finds itself in the sorrow that the writer, viz., Martin Gore, had to bear witness; or perhaps the blasphemy is in the chorus of the song, the incredibly catchy chorus, where the song rises up from its sluggish verse, its goth verse, into the gospel affirmation of the chorus, an ostinato of a melody that feels very Beatles-ish, in which the narrator repeats, “I don’t want to start any blasphemous rumors, but I think that God has a sick sense of humor, and when I die I expect to find him laughing.”

What’s revealing in this catchy chorus is first the blunt expectation of the narrator’s own death (it’s always an excellent lyrical trope—in the blues, or in “My Generation,” or just about anywhere, the foreknowledge of the narrator’s own death), but further there is an implication in the chorus that God’s omnipotence is limited, and just as he/she/it cannot prevent the suicide attempt in verse one, God also cannot prevent the car crash in verse two: “Girl of eighteen, fell in love with everything / Found new life in Jesus Christ / Hit by a car, ended up on / A life-support machine / Summer’s day as she passed away / Birds were singing in the summer sky / Then came the rain, and once again / A tear fell from her mother’s eye.” One wants to ask if this character is the same as in verse one, but let’s say instead that in verse two the girl is simply one other example of the flock who, according to the theology of Depeche Mode, is unable to sidestep tragedy, this time in the form of a car accident, despite her faith, and this inevitable tragedy is ironic, as in verse one, or so it seems. After which we get the chorus again, with multiple reiterations, and thus multiple invocations of Martin Gore’s own death, or David Gahan’s death (if you accept the idea that Gore writes for Gahan’s point of view).

This would be the interpretation according to the commandments of Anglican atheism, according to the rigidities of the drum machine and its ethos. People suffer, God laughs. But what if the irony is even deeper than it looks, and what is happening here is that Gore’s ability to observe the hardships and tragedies of his core audience, the teens of the suburban latitudes and their aggrieved parents, is somehow generous, strangely generous, and that a laughing God, a sort of a Buddhist God, who perhaps laughs only with sorrow, is somehow the only one to expect, and that what is under scrutiny here, in the song, both lyrically in the chorus and in its sad, dirgeful verses, is not theology as a whole, but just a slightly moronic theology that expects an easy, parking-space God who oversees the minutiae but which gets, instead, not a callous God, but a noninterventionist, compassionate God who, as Tolstoy said, sees the truth but waits, and whose compassion is, in this case, being redoubled by the compassion of a songwriter who feels much, e.g., his own death.

I’ve said little about the music, which I still find rather moving despite the dated sequencers and the plodding drum program (a Roland drum or a LinnDrum). But it bears mentioning that in the single edit of the song, with one minute remaining, the drum machines give out, and there is a sort of plangent inspiring of breath (the protagonist on the life-support machine, perhaps). It can’t, this section, have received much airplay when the song was in wide circulation. But it is integral to the full spectrum of threnodic misery here. In short, “Blasphemous Rumours,” despite its modest origins, rises to a level of strange, ambiguous spiritual insight, especially when the drum machines give out at the end and it affirms the unlimited agape of the divine space, and even admits to an afterlife, all this even as the song preserves a sort of cynical veneer for those who do not feel invited into the greater profundities.

A second stop in any theological tour of Depeche Mode must land at “Personal Jesus,” from Violator (1990), which, frankly, is a very good song. “Personal Jesus,” at the very least, is the endpoint for a certain kind of Depeche Mode, for the simple reason that it’s the first time that the band permitted the unalloyed use of an electric guitar. They had, it is said, sampled guitars before, but they had not made the electric guitar the mainstay of a composition, as it assuredly is in “Personal Jesus,” since the whole is organized around a blues riff that wouldn’t have been out of place on a song by Stevie Ray Vaughan or Eric Clapton. Martin Gore describes “Personal Jesus” thus: “It’s a song about being a Jesus for somebody else, someone to give you hope and care. It’s about how often that happens in love relationships—how everybody’s heart is like a god in some way.” However, if this was meant therefore to be a secular composition, in which Jesus is just one aspect of the contemporary relationship, “some radio stations interpreted it as a ‘religious tribute.’” And no less an expert than the Man in Black, a.k.a. Johnny Cash, was willing to throw his weight behind this religious interpretation, when he later covered the song (with the usual sublime touch) on American IV: The Man Comes Around: “That’s probably the most evangelical song [I’ve] ever recorded. I don’t know that the writer ever meant it to be that, but that’s what it is.… It’s about where you find your comfort, your counsel, your shoulder to lean on, your hand to hold on to, your personal Jesus.”

“Personal Jesus” was a monster of a song; it changed the landscape for Depeche Mode entirely; it crossed over; it had massive global penetration. From a careerist perspective, it enabled the longest and largest tour of the band’s history, which made possible the beginning of David Gahan’s drug problem. It also created a need for something Depeche Mode had never needed before: a live drummer. Alan Wilder served in that capacity occasionally, and then, when Wilder left, the role was mainly occupied by one Christian Eigner.

True, there was a lot of programming, and live drums playing along with synthesized drums, but there was also in Depeche Mode, after Violator, a lot of faith; their next album, in fact, was called Songs of Faith and Devotion, and it featured an out-and-out gospel number called “Condemnation,” as well as another, only marginally concealed, called “Higher Love.” The tendency toward articulations of spiritual material, furthermore, was not confined to albums released during Gahan’s heroin addiction, either, because once he was clean, the band made Playing the Angel (2005). Sounds of the Universe (2009) includes “Peace,” a chant of the frankly spiritual sort: “I’m leaving bitterness behind this time / I’m cleaning out my mind,” and, later, “I’m going to light up the world.” Not exactly the brooding, self-absorbed, bondage-and-discipline light synthetic pop you associate with a band of squeaky-clean naïfs from the early 1980s. Which indicates, it seems, the limitation of the approach, the limitation of the Kraftwerk-influenced, rhythmically organized, drum-machine-addicted nihilism of early British electronic pop. You can’t live like that forever. If you are lucky enough to survive living that way (which Gahan did, by surviving his heroin addiction; which Gore did, by surviving his drinking-related seizure disorder; which Fletcher did, by overcoming multiple nervous breakdowns during the Violator period), you can’t help, it seems, to begin to express some gratitude. And then the music begins to reflect this gratitude, this human feeling.