You’ll find them in Times Square, along Sunset Boulevard in L.A., and in most cities, big and small, working the sidewalk outside a strip of nightclubs at 2 a.m.—guys hustling their homemade rap CDs. “Hey man, you like hip-hop?” the pitch invariably begins. Nod your head ever so slightly and you’ll have a pair of headphones slipped over you, a ragtag beat banging in your ears. After a thirty-second taste, they’ll try and sell you their album for five to ten bucks, though they’ll take three dollars, even one, if you care to bargain. I never do; ten bucks is already a bargain. Attention, young rappers! I’m an easy mark. I will always buy your CD.

All of my favorite rap albums are CDs I bought on the street. I mean, I like some commercial rap, I like some underground hip-hop, but the shit I really get down with is downright subterranean. I love the murky production values; I find it exquisite when someone rhymes a word with the same word. But it’s not the campiness that captivates me, it’s the urgent sincerity, the flares of emotion, the specificities of small but stinging daily struggles. Inside the odd, sparse beats and untreated vocals, I can imagine the scene where the music was recorded: three teenagers in a makeshift basement studio, joined, perhaps, by a couple of younger siblings—one looking on watchfully, the other tugging at pant legs, demanding a turn with the mic. I don’t want my rappers driving Escalades; I want them begging rides from their friends, or driving the same beat-up piece of shit as me.

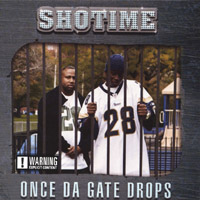

Thankfully, the sleek and sanded major-label concoctions on sale at Circuit City are counterbalanced by hundreds, maybe thousands of great, unheard albums like, for instance, Shotime’s Once Da Gate Drops. Shotime is Andre Jackson, from the Soundview neighborhood of the South Bronx. I met him a few years ago when he was eighteen, hawking his CDs on the subway, and by the time I’d listened all the way through his album, I was a fan for life. Highlights: “Friday Nite,” an elegy to club-hopping; “Luv of My Life,” a rugged, wistful ballad; and “High Rolla,” where he boasts of stacks of cash he surely doesn’t have. These kinds of songs are hallmarks of homemade rap albums. The thing is, when broke rappers rap about driving Range Rovers and Benzes, and wearing diamonds the size of fists, their voices crack with a kind of hopeless hopefulness that delivers its own particular brand of heartbreak.

Not every rap album you buy directly from the rapper who rapped it is a work of undiscovered brilliance. Some are unlistenable. Some don’t play in any CD player or are actually blank. But this element of mystery and intrigue is part of the excitement. And by and large, there’s magic in these CDs. Mississippi’s G Town Hustlers; Phoenix, Arizona’s D-Shot; Classified, from Halifax, Nova Scotia—these are the rap world’s Daniel Johnstons, recording in bedrooms, in love with making music, a bit addled, perhaps, but also a bit visionary. I can’t help but respect the punk-rock, DIY spirit of anybody who makes art and tries to sell it to strangers on the street. After all, I do the same shit myself: Every year I hop in a van and go city to city selling my zines.

The best track on Shotime’s album, by a long shot, is “S-H-O-T-I-M-E,” which has replaced Metallica’s “One” as my hype song when I’m out in my van, drinking before a Found magazine show. It’s a fierce anthem, grimy as fuck. Shotime shouts, grunts, even growls his refrain: “I’m on the grind; I’m on the grizz-ind.”

One night on our Found tour last fall, my Belgian friend Benoit, who was playing roadie, asked me in his clipped accent, “What is this, grizz-ind?”

This is the grizz-ind, I explained: selling magazines out of the back of a van, sleeping on park benches. Benoit nodded gravely and took a sip of his Maker’s Mark. Then he looked up at me with a thoughtful look. “I also am on the grizz-ind?”

“Yes, Benoit. You also are on the grizz-ind. And I am on the grizz-ind. Both of us. And Shotime.”

We clunked whiskey bottles. “To the grizz-ind.”

—Davy Rothbart