“Do you solemnly swear that the evidence you are about to give in this matter is the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth?”

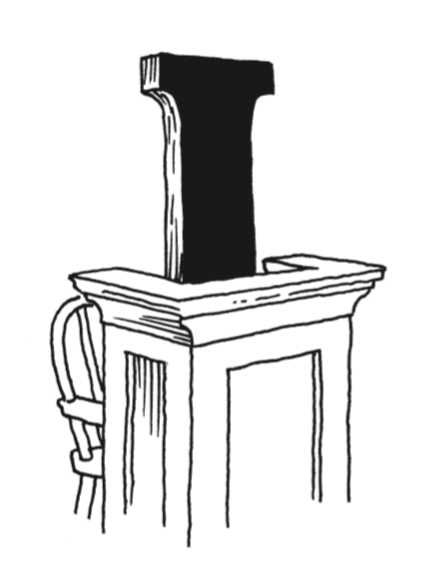

Let’s start with the facts: Three hundred of us, being citizens of this United States, are selected randomly and called to the Kent County Circuit Courthouse, Grand Rapids, Michigan, on a Monday morning. It is drizzly, dreary. I am barely awake and have a poor outlook on the world, which is operating in gray scale. Out of the three hundred, thirty of us are called to make up a potential jury for a trial overseen by Judge Redford on the eleventh floor. I am one of the first five. We rise, are asked to turn our cell phones off, and proceed upstairs where the real action will happen. Of the thirty, I am one of the fourteen randomly selected for the jury, pending voir dire in which we are asked to answer questions truthfully about our biases and histories. We are seated in the box, quiet, awaiting instructions. There are no snacks allowed.

I didn’t expect to be summoned to the courthouse, as I listed my occupation on the form I received in the mail a couple weeks earlier as “writer/journalist.” Certainly lawyers, judges, and jury clerks wouldn’t want a writer-slash-journalist involved in deliberations of guilt? Said writer might be tempted to try to take notes and make something of the experience—document it, repurpose it, make it about himself. “Journalist,” however, is a little bit of a stretch for me, as I wouldn’t characterize my writing—even my nonfiction—as journalism, though it does deal in truth, fact, and in verifiable research. As such it perhaps deserves the slash and moniker: its sentences are heavy with actual, demonstrable truth content; the result is not mistakable for memoir. But I am called to the courthouse anyway, and the rhetoric of civic duty as one of the sacred tenets of American law and citizenship means that I am actually not so disappointed. I grew up watching L.A. Law, Law & Order, The Practice, and Perry Mason. I read some Grisham, have been to court myself under different conditions. I think I want to be chosen. And I am.

Anyone, any given I, any one of you, of y’all, of youse guys (as they say in my hometown), any one of the big mess of us could find ourselves impaneled on a jury. The jury process is a great argument for the education of citizens, particularly using the model of liberal education we endorse at the college where...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in