1.

The animated shorts of Brent Green have played at a variety of venues: in film festivals like Sundance, in museums like the Hammer in L.A., in bars with both Green and a band providing a live soundtrack. Self-taught in his artistic pursuits and collaboratively minded, Green has always made things by hand. His aesthetic privileges imperfection over slickness. The tape holding together his animation cels, for example, is often visible; the light changes dramatically between frames. In Hadacol Christmas (2005) and Paulina Hollers (2006), Green used his signature handmade puppets and animated pen-and-ink drawings. With Carlin (2007) he got “big,” using a life-size puppet, a real wheelchair, and real birds and bees. Tinkerer Used to Be a Trade (2009) incorporates a person for the first time (Green’s girlfriend, Donna Kozloskie); she’s placed in minutely adjusted positions for each individual frame, treated as though she were a 2-D animation.

In addition to Green’s narration, supplemental audio support is provided by various talented musician friends, including Califone, Brendan Canty, and Howe Gelb.

Echoing this homegrown spirit, Green recently erected, on his family’s land, an actual town in which to shoot his first feature film, Gravity Was Everywhere Back Then. Last July, I went to see this town. I flew into a large city, took a train to an old stop, and drove over rolling hills until I arrived at the refurbished barn where Brent and Kozloskie live. Beside the barn is Green’s childhood home, still damaged from a fire that burned years ago.

2.

The first thing you notice about Green’s backyard isn’t the buildings, but a network of poles and wires, along with various ropes and pulleys, used to suspend the wooden stars that shine over the new town. (All of the lights inside the stars are attached to separate dimmers so that Green can control the twinkle.) A giant dark cloth can be drawn around the perimeter to black out the rest of the world. At night, it’s pretty damn gorgeous.

Five houses surround a central dirt “main street.” The houses are actually quite sturdy, built from the salvaged wood from two derelict barns on the property. The more I look at the buildings, the more I start to notice odd touches: not-quite-right angles, things leaning where they shouldn’t, windows that are almost square. The sets don’t look built so much as they seem scripted.

Four of the houses are two-story-tall facades, with working doors and windows. One house—in which most of the film takes place—is almost livable. It has electricity, walls, a living room, a kitchen, a bedroom, and a toilet (but no plumbing).

A spiny circular stairway on the second floor will eventually lead to a small tower. The tower has already been built, and is waiting to be attached. Currently it sits near a twenty-foot-tall cabinet that houses an eighteen-foot-tall crescent moon Green made from balsa wood.

“Every morning I wake up, I look outside to see if the town is still standing,” Green says. “I could use a Black and Decker sponsor.”

3.

Gravity is inspired by a man named Leonard Wood, who is from outside Louisville. When Leonard’s wife, Mary, became ill with cancer, he believed that if he built a house by hand, it would save her life: it would be a healing machine. Mary passed away in 1972, but Leonard continued building for decades, nearly up until his death in 2008.

One day Leonard fell off the roof and, though he survived, he couldn’t work anymore. He sold the house and moved into a nursing home. When the house was scheduled for demolition, it came to the attention of Brendan Canty. Canty produces a DVD series called Burn to Shine that features local bands in different cities recording songs in houses that are about to be destroyed. Green accompanied Canty to film the house.

The house was “randomly, chaotically filled up with rooms,” Green says. Each stair was numbered. The floor of one room was placed halfway up a doorway so that you had to hoist yourself inside. Another room featured a twenty-three-foot vaulted ceiling. Each windowpane was painted a different color. (Green used glue and food coloring on his windows to achieve the same light effect.)

All of Leonard’s personal effects were still in the house when Canty and Green arrived. Clothes, bills, letters of homegrown philosophy, food in the fridge. There were cassette tapes of Leonard playing the piano, and blueprints for the house written on cardboard.

Building a house as medicine seems like a bizarre form of therapy, “but he wasn’t an idiot,” Green notes. “It’s physically trying to create a miracle, like praying, or Noah building an ark.”

4.

Green’s film, while inspired by the story of Leonard and his heartbreak, is in no way a biopic. In Green’s script, for instance, the characters meet in a car crash. “Movie-Leonard” soars through the air (and two windshields) to land in Mary’s car.

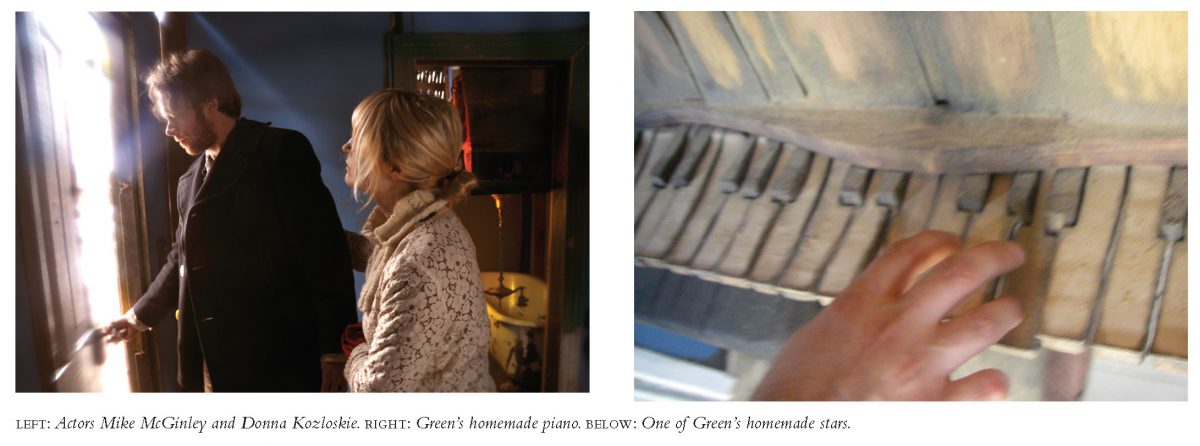

The houses, too, are as much fanciful real-life extensions of Green’s drawing style as they are inspired by Leonard’s creation. A reading chair features a long wooden arm that rises up behind the sitter, and then curves down in front with a light bulb on the end. The entire front wall of the main house is suspended on hinges and opens up like a giant dollhouse. There is also a wooden oven and a working wooden piano (Green carved the keys, the pedals; everything by hand.) The houses and the objects in them will eventually tour museums and galleries with the film.

This will also be Green’s first time working with speaking actors. “I would need a thousand drawings of heads to properly convey the emotions,” he says. To shoot the dialogue for Gravity, Green takes a single frame while each actor speaks one syllable at a time. Then, the actors will re-record the dialogue normally. That track will be placed over the finished video, so the animation and the dialogue match.

Kozloskie plays Mary. Essential to Green and the film, she helped build the town, made clothing, and collaborated on the script. Leonard is played by Mike McGinley, from the Chicago band the Bitter Tears.

Green cast them because they each reminded him of the characters he wrote. “The script needed more humor,” Green says. “They are both really funny and quiet, charismatic people. Mike looks like a young Tom Waits. He’s even missing teeth.”

5.

Toward the end of my trip, Green shows me a little test footage of Donna-as-Mary wandering around inside the house. The dialogue sounds normal, making the images even more mysterious, a fairy tale played out in real time.

Green shows me a letter Leonard wrote to Mary in 1985:

Dear wife Mary –

I love you so! Please, if you will, let me hear from you, Darling. Perhaps you can make some words to appear through the written medium, like this. I won’t be frightened, since I feel so close to you, loving you so much. I miss you more, all the time. Please, if no other way, maybe you could somehow allow yourself to manifest in my dreams. I miss you and love you so very, very much.