AN OPPONENT OF DIGNIFIED BUNK

When Emanuel Haldeman-Julius drowned in his backyard swimming pool, on July 31, 1951, he was popularly regarded as a has-been, even in his adopted hometown of Girard, Kansas. Denounced as a communist in national newspapers and investigated by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, he had recently lost a federal tax evasion lawsuit and was facing time in jail. Amid the cold war atmosphere of the time, schoolchildren around Girard whispered that Haldeman-Julius had actually been assassinated for being a Soviet spy; adults speculated that his death was a suicide—though the only note he left behind contained a silly joke meant for his wife.

It was an odd ending for a man who, in just over thirty years, had become one of the most prolific publishers in U.S. history, putting an estimated 300 million copies of inexpensive “Little Blue Books” into the hands of working-class and middle-class Americans. Selling for as little as five cents and small enough to fit in a trouser pocket, these books were meant to bring culture and self-education to working people, and covered topics ranging from classic literature to home-finance to sexually pleasuring one’s spouse. Distributed discreetly by mail order, Little Blue Books disseminated birth-control information not available in small-town libraries, advocated racial justice at a time when the Ku Klux Klan influenced politics, and introduced Euripides, Shakespeare, and Emerson to people without the means for higher education.

Haldeman-Julius’s Kansas press debuted writers like Will Durant, Bertrand Russell, and Clarence Darrow to the American public, and titles by Henry James found more readers in their Little Blue Book editions than in those from any other contemporary publisher. Endorsed by Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia and carried to the south pole with Admiral Richard Byrd, Little Blue Books figured in the early education of twentieth-century writers like Saul Bellow, Ralph Ellison, Studs Terkel, Harlan Ellison, Louis L’Amour, Margaret Mead, and Langston Hughes.

In the midst of his publishing heyday, when asked how he might be remembered, Haldeman-Julius speculated that his obituary would mention how “I sold hundreds of millions of [books] and usefully served a portion of my generation with fairness, sincerity, and intelligence…. It may mention my forthright attacks on all forms of Supernaturalism, Mysticism, Fundamentalism, and respectable and dignified bunk in general.

“It may even go so far as to say that I changed the reading habits of Americans and created millions of new readers for the book publishers who followed me.”

After his death, national obituaries indeed cast the Kansas publisher as a kind of huckster visionary, though his influence was quickly forgotten as postwar prosperity and the advent of television ushered in a new era of mass culture. To this day, there is little public memory of Emanuel Haldeman-Julius’s contribution to American society, even in Girard (where a small plaque near the town square is his only commemoration). Used volumes of Little Blue Books are revered, if at all, by a smattering of book collectors and eBay hobbyists.

It’s a strangely anonymous legacy for such a remarkable man, especially since—until the advent of the Internet decades later—no single venture brought so much information across such great distance to so many Americans at so little expense.

MARK TWAIN WAS A SOCIALIST.

Born in Philadelphia in 1889, Emanuel Julius was the son of Russian-Jewish parents who’d immigrated to America from Odessa two years earlier. His father, who’d simplified the family name from Zolajefsky, found work as a Pennsylvania bookbinder, and young Emanuel found fascination in books at an early age. At age thirteen Emanuel quit school to become an usher at the Keith Theater, and later a bellboy at Miss Mason’s School for Girls (“an educational rolling mill to turn pretty virgins into capable and successful wives”). What money did not go to his family he spent on books—though cheap books were in short supply in those days, and he would later remark that “seeing a book I could not afford to buy was worse than being hungry and looking at a bun in a bakery window.”

In an episode he went on to recount many times, Emanuel found his life’s mission at age fifteen, when he spent a dime on a used copy of Oscar Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Jail and spent a winter afternoon sitting on park bench, reading it from cover to cover. “Never did I so much as notice that my hands were blue, that my wet nose was numb, and that my ears felt as hard as glass,” he wrote later. “I’d been lifted out of this world—and by a ten-cent booklet. I thought, at the moment, how wonderful it would be if thousands of such booklets could be made available…. easily and inexpensively, whenever one wanted to buy them.” Fifteen years later, when Haldeman-Julius published the first batch of what were to become known as Little Blue Books, The Ballad of Reading Jail was among the initial titles.

In addition to being an impassioned reader, Emanuel was also a budding writer, and it was during his teenage bellhop stint that he sold his first article, “Mark Twain—Radical,” to the International Socialist Review. The essay, which argued that Twain was at heart a socialist, earned him ten dollars. This success led to work as a copyreader at the socialist Philadelphia Daily, and his writing talents soon led to reporting stints at socialist newspapers around the country, including the Milwaukee Leader (where he worked alongside Carl Sandburg), the Chicago Daily World, and the Los Angeles Citizen. He ultimately landed at the New York Call, where over the course of several years he worked his way up to the position of Sunday magazine editor. Short and stocky with gray eyes, jet-black hair, and a soft baritone voice, the young journalist haunted the Greenwich Village socialist scene, rubbing shoulders with likes of Emma Goldman, Eugene O’Neill, and Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Emanuel’s true call to destiny, however, did not come until 1915, when editor Louis Kopelin offered him a 40 percent pay-raise to write for the Appeal to Reason, the Kansas-based socialist weekly that at its zenith a decade earlier had printed more copies than the Sunday edition of the New York Times, and whose press had been dubbed “The Temple of the Revolution” by Jack London.

THE UNLIKELY LITERARY RISE OF GIRARD, KANSAS

How the most successful socialist newspaper in American history came to be based in Girard, Kansas, is a curious tale of geographic determinism and creative enterprise. Founded on former Cherokee neutral land in 1868, the town of Girard gradually grew to around three thousand residents by the end of the nineteenth century. Southeast Kansas saw a coal and zinc mining boom around the same time, and an influx of immigrant miners from Italy, Germany, Austria, France, and Scotland lent an international feel to the region. Banking on the socialist sympathies of this immigrant community—as well as the cheap cost of living and the ease of sending mail-order editions to both coasts—a newspaperman named J. A. Wayland relocated his fledgling Appeal to Reason from Kansas City to Girard in 1897.

Over time, the newspaper’s penchant for zealous, hard-hitting journalism (Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle was underwritten by the Appeal, and first appeared as a series of articles in 1905) led to a boom in mail-order subscriptions, and prosperity brought new jobs to Girard. Though the mission of the paper was “to war against oppression and vast wrongs, dispelling the tears, the blood, the woe of capitalism,” Wayland had natural business instincts. Resisting the complications of collective ownership, he used his mailing list to sell products from the Girard Manufacturing Company (an Appeal subsidiary), thus stabilizing his newspaper’s cash flow. At one point, the paper boasted subscriptions of more than six hundred thousand weekly copies, making it the biggest-circulation political newspaper of its time. Though some chafed at the notion that Wayland was earning a healthy profit under the guise of socialism, Girard found its way onto the American political map, and in 1908 Eugene V. Debs accepted his Socialist Party presidential nomination with a fiery speech on the steps of the local courthouse. Decades later, scholar William F. Ryan called the town “a hostelry for socialists, freethinkers, and village atheists hob-knobbing with the dirt farmers and coal miners of southeastern Kansas, and turning out some of the hottest, toughest journalists the nation had seen in a century.”

Though many of the causes promoted by the Appeal to Reason are now commonly accepted as worthy (the forty-hour workweek, universal suffrage, the end of child labor), the newspaper encountered steady resistance from the federal government, including numerous slander and obscenity charges. During the Taft administration, an Appeal editor was convicted and sentenced to time in Leavenworth Penitentiary on obscenity charges for printing an article describing “degenerate practices” in that very prison. (“When they get me in there they will practice on my body these same abominations until they kill me,” the editor wrote after his conviction; he was later released on appeal.) A more devastating blow to the paper came in 1912, when an embattled J. A. Wayland committed suicide, “hounded to death,” his newspaper claimed, “by the relentless dogs of capitalism.” By the time Emanuel Julius arrived in Kansas to write for the paper, in 1915, the Appeal to Reason was in the midst of a decline from which it would never recover.

Fatefully, the twenty-six-year-old reporter showed up not long after an aspiring stage actress named Marcet Haldeman returned to Girard from New York to attend her mother’s funeral. Marcet was poised to inherit the town bank (which had been established by her father and run by her mother after his death)—but only on the condition that she first live for one year in Girard. For most men in southeast Kansas, this independent-minded, cigarette-smoking, Bryn Mawr–educated twenty-eight-year-old must have seemed intimidating; to Emanuel Julius, she was the perfect catch. After six months of courtship, the two were united in “companionate marriage” (a radical notion at the time, since the arrangement embraced financial independence, balanced responsibilities, and birth control). Not long after the wedding, Emanuel formally took Marcet’s name, appearing in print thereafter as Emanuel Haldeman-Julius.

As Haldeman-Julius settled into married life, the Appeal to Reason slowly unraveled. After a series of editorials attacking American militarism and conscription policies during the First World War, the federal government rescinded the paper’s second-class mailing rights. This, combined with the post–Russian Revolution “Red Scare” and the restrictions of the Espionage Act (as well as infighting among American socialists), led to a drastic reduction in subscriptions. Seeing an opportunity to make changes, Haldeman-Julius used twenty-five thousand dollars of his wife’s money to buy controlling interest in the Appeal, on the understanding that he would come up with another fifty thousand in one year.

Haldeman-Julius’s scheme to raise that money—a publishing venture whereby his newspaper presses were used to print inexpensive books on a variety of social and intellectual topics—proved to be far more popular in the years that followed than did the newspaper he was trying to save.

BOOKS FOR THE WORKING MAN’S POCKET

Financial necessities aside, there were several factors that inspired Emanuel Haldeman-Julius to print what would eventually come to be known as the Little Blue Books. In addition to his teenage Oscar Wilde epiphany in Philadelphia, Haldeman-Julius had been corresponding with Marian Wharton, the head of the English department at the People’s College of Fort Scott, thirty miles north of Girard. Wharton wanted inexpensive literature that could be used at the socialist college, so he printed her copies of The Ballad of Reading Jail, as well as The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám—which he also offered for twenty-five cents each to the 175,000 subscribers on the Appeal’s mailing list. These books proved so popular that Haldeman-Julius announced his intention to publish a series of classics. The entire fifty-book series could be had for five dollars—and when five thousand orders arrived after the first week, the publisher diverted his energies into creating more titles and publishing more books. “I thought that it might be possible to put books within the reach of everyone, rich or poor,” he wrote. “By that I mean I dreamed of publishing in such quantities that I could sell them at a price which would put all books at the same cost level.”

Initially called “The Appeal’s Pocket Series,” individual titles sold for twenty-five cents. From the beginning of his publishing project, Haldeman-Julius made an effort to promote controversial rationalist and sex-education writings not available from other outlets. At a time when many working-class Americans didn’t finish high school—let alone attend college—his books aimed to inform, provoke discussion, and promote independence of thought. Many of the books were public-domain reprints of classics, which included “all the famous authors from Aesop to Zarilla”—though he also hired freelancers to write original books, often on political or how-to topics. Protofeminist Margaret Sanger, for example, was recruited to write about birth control (a taboo subject at the time). Sherwood Anderson contributed short stories, and Theodore Dreiser penned How the Great Corporations Rule the United States. Scores of lesser-known writers weighed in on various other topics, from Great Pirates and Their Deeds to How to Make All Kinds of Candy. An atheist himself, Haldeman-Julius made it a point to publish excerpts from sacred books as well as tracts on skepticism. “I am against all religion—I think the Bible is a dull book,” he later wrote. “Yet I print the Bible, and in the face of an appallingly low annual sale I keep the book in the series. I do this out of stubbornness. I am determined, because I know I am prejudiced against the book, to give it more than a fair chance. Could supporters of the Bible ask any more of one who does not like it?”

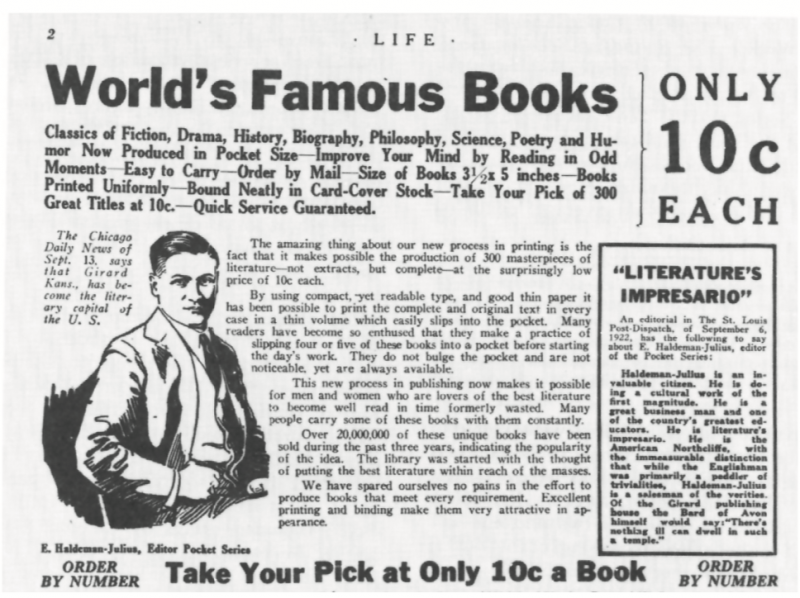

Ongoing success and increased production allowed the price to drop to ten cents per book by 1922. While the socialist media gushed (one paper dubbed Girard “The Literary Capital of the United States”), the mainstream press was at first skeptical. Writing in the August 1922 issue of The Smart Set, H.L. Mencken noted “the editing and printing [of the books] show all the usual Socialist incompetence.… It is not agreeable to think of a poor man laying out his money for such garbage, and then solemnly digesting it. He’d be much better occupied asleep in the sun.”

Mencken’s criticism points to the fact that Little Blue Books were not the first literary effort aimed at the working class. A decade prior to Haldeman-Julius, Charles H. Kerr & Co. of Chicago published a seventy-two-title “Pocket Library of Socialism,” volumes of which were sold at political gatherings. In the 1870s, a series called “Bohn’s Library” aimed to bring non-Bible literature into working-class homes. Indeed, populist literary publishing in the United States may well date back to the early 1840s, when new papermaking machines allowed newsweeklies like New World and Brother Jonathan to cheaply serialize novels in broadsheet form.

What set Haldeman-Julius’s venture apart from previous efforts at providing cheap books for the masses was his flair for promotion, his willingness to adapt to market needs, and an unwavering sense of mission. By 1924 he had brought in an upgraded cylinder press that could churn out forty thousand books in an eight-hour period, and he was able to further reduce the price of his books to five cents by limiting their size to three and a half by five inches, keeping the page-count at around fifty to sixty pages, and using the cheapest heavy-grade paper available (which happened to be colored blue) for the covers.

Haldeman-Julius eventually tired of blue and dabbled in other cover colors, but the association stuck: titles in the burgeoning literary series were known as “Little Blue Books” for the remainder of their existence.

THE TRUTH ABOUT THE LITTLE SECRET OF FACTS YOU SHOULD KNOW

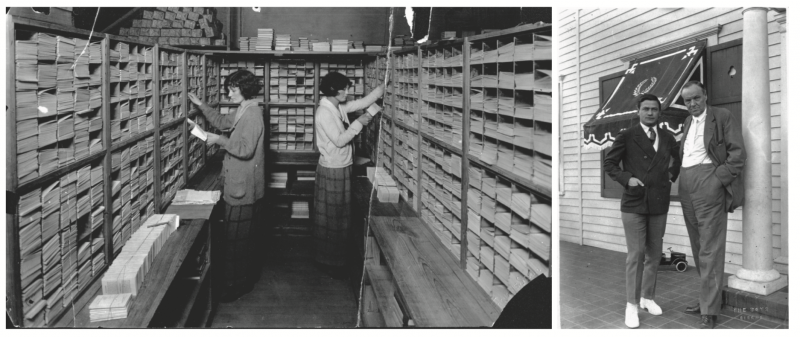

Throughout the 1920s, potential readers could purchase Little Blue Books in a number of ways. Initially, lists of titles in the pocket-book series were sent to Appeal subscribers, but by 1922 Haldeman-Julius had discontinued the failing newspaper and was promoting his books through sensationalistic advertisements in magazines like Life, Popular Science, and Ladies’ Home Journal—as well as in newspapers like the New York Times and the Kansas City Star. “At last!” the ads read. “Books are cheaper than hamburgers!” Once, when an ad was lost at the last minute, Haldeman-Julius replaced it with a announcement that read: “Would You Pay $2.98 for a High School Education?” The ad resulted in thousands of orders for books; by the late 1920s, Little Blue Books were subtitled “A University in Print.” To save ad space, only the book titles were listed, organized by topic-headings like “Philosophy,” “How-To,” or “Sex.” Customers checked off the titles they wanted and mailed in the order form; one dollar—twenty books—was the minimum order.

Flush with the success of his mail-order business by the mid-1920s, Haldeman-Julius set up Little Blue Book franchise stores in cities including Boston, Buffalo, Atlantic City, Montreal, Cincinnati, Milwaukee, Atlanta, San Francisco, and Portland. The Los Angeles store placed an initial order of 275,000 titles; the Detroit store reportedly sold 300,000 copies in two weeks. In New York, Little Blue Books were sold from subway vending machines, and at one point Haldeman-Julius talked about converting trucks into mobile bookstores that could service the rural population.

In the end, however, ad-driven mail orders constituted the bulk of Little Blue Book business, and Haldeman-Julius was savvy at getting the most out of a given advertisement. Stodgy-sounding socialist treatises were repackaged as self-help titles; books with vague-sounding subject matter were renamed with provocative teasers like “The Truth About…” or “A Little Secret That…” When Schopenhauer’s Art of Controversy was advertised as How to Argue Logically, sales jumped from a few thousand to thirty thousand per year; when Whistler’s Ten O’Clock was renamed What Art Should Mean to You, sales quadrupled. Haldeman-Julius had learned this technique from his days as a newspaper headline writer, and he made no apologies about his retitling strategy. “An important secret of successful titling is to be imperative,” he wrote, “to insist in the very name of the book that the reader have it. Now Life Among the Ants was much improved in its distribution by extending it thus: Facts You Should Know About Ant Life.… The public today wants facts and it likes being told that it is getting facts.”

As Haldeman-Julius readily found out, the public also liked titillation. Guy de Maupassant’s The Tallow Ball sold three times better when entitled A French Prostitute’s Sacrifice, and sales of Gautier’s Fleece of Gold jumped from six thousand to fifty thousand when it was retitled The Quest for a Blonde Mistress. “What could Fleece of Gold mean to anyone who had never heard of Gautier or his story before?” Haldeman-Julius wrote. “Little, if anything.… The Quest for a Blonde Mistress [is] exactly the sort of story it is.” In this way, a book about Abelard and Heloise was sold as The Love Affair of a Priest and a Nun.

In his 1928 book The First Hundred Million (an early account of his publishing ventures; the title refers to the number of Little Blue Books he’d sold up to that point), Haldeman-Julius claimed that his title tweaks made great literature more human and accessible to the kinds of people who wouldn’t otherwise read it:

If you can make the lowbrow believe that Ibsen, Wilde, Shaw, Voltaire, Emerson, and other rather forbidding persons are human beings with a very human appeal—they will buy readily, because the name means nothing. They do not buy by the name of the author but by the suggestion that the material in the book will interest them.… Too much effort cannot be expended in making it clear to modern readers that when Aristophanes and Sophocles and Euripides, for example, wrote their powerful dramas they appealed to their people not because they were writing “great plays” but because they depicted life in a manner that the Greeks of their day could recognize and understand.

Though occasionally skeptical of his methods, the mainstream media eventually took note of Haldeman-Julius’s successes. The New Republic wrote that “the volume of his sales [is] so fantastic as to make his business almost a barometer of plebian taste”; a New Yorker profile observed that Haldeman-Julius must feel “the crusader’s pride” when, riding the subway on a visit to New York, “he sees a workman settle back on his strap and reach automatically to the pocket where he keeps his Little Blue Book.” Perhaps the most effusive praise came in a 1924 McClure’s article, which claimed that Little Blue Books were “spreading like beneficent locusts over the country,” and suggested that they would “help break down America’s cultural isolation.” “The best peace propaganda in the world is to make the culture of the whole world known to the whole world,” the article enthused, calling Haldeman-Julius “a creative genius who was blazing a more glorious path of service on principles akin to those of Ford.”

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch had, in fact, already called Haldeman-Julius “the Henry Ford of Literature” (other periodicals variously dubbed him “the Book Baron,” “Voltaire from Kansas,” and “the Barnum of Books”), though the publisher took issue with Ford’s anti-union tactics, and at one point penned a contentious Little Blue Book titled What the Ford Five-Day Week Really Means. In truth, while Haldeman-Julius’s business had indeed veered into capitalist-style mass marketing and mass-production tactics, he still claimed to hold true to his early socialist ideals. “I would not ‘do anything for money,’” he once wrote in response to a critic. “I am glad that my profits have not come from the manufacture of munitions of war, for example. I am glad, in other words, that I have been able to use good business toward improvement instead of exploitation of the masses.”

AVERAGE MAN V. SELF-STYLED, SUPERIOR MAN

To understand the effect Little Blue Books had on “the masses” requires an understanding of what it was like to live in America in the 1920s. Despite the “roaring twenties” stereotype, some estimates assert that 40 percent of American families lived at or below the poverty line—and cultural life outside certain urban enclaves suffered from the psychic isolation that came with the limitations of social class and physical distance. Women and minorities did not share the same rights and opportunities as white males; rural and small-town libraries were typically beholden to conservative busybodies and did not provide information about sexuality, activist politics, or evolutionary science. Universal education was on the upswing, but few Americans went to college and most of the literature targeted at the increasingly literate working class consisted of pulp magazines, newspapers, and comic books.

At the heart of Emanuel Haldeman-Julius’s publishing project was his conviction that broad personal information-access was essential to a full realization of the American Dream. As scholar Eric Schocket would later observe in an essay titled “Proletarian Paperbacks,” Little Blue Books “brought a heterogeneous mixture of literary culture, self-help, indigenous socialism, and free thought into the homes and lives of farmers and workers who as often as not found themselves on the margins of modernity, held rapt by the glow of ‘electric light towns,’ but left out of the economic boom of the postwar years. The history, the content, and even the format of the Little Blue Books provide a valuable sense of the cultural desires of a generation on the borders between production and consumption, tradition and technology, poverty and abundance.”

Thus, while Little Blue Books enjoyed a broad readership, and many of the titles reflected middle-class aspirations (“How to Own Your Home”; “How to Enjoy Orchestra Music”), they were created with a blue-collar demographic in mind. Unlike the leather-bound “Great Books” collections aimed at more bourgeois audiences, Little Blue Books were of little use on the shelf. Small and portable, containing almost no illustrations, they were designed to be read (and passed on) amid the idle moments of a workday routine: during breaks, on bus transits, in stolen moments while infants were napping. Starting in the 1920s and continuing into the years of the Great Depression, de facto libraries of Little Blue Books accumulated in hospital wards, factory break-rooms, and prison cellblocks. “American readers are thorough in their quest for knowledge,” Haldeman-Julius wrote. “They place no taboos of their own on anything which may inform them or help them to understand the world and themselves. One of these days Mr. Average Man may resent being deprived of a book he wants to read, just because some self-styled Superior Man says it won’t be good for him.”

Study the Little Blue Books sales numbers and it becomes apparent that the Average Man (and Woman) of the 1920s and ’30s wanted to read more about sex. In 1927, for example, two of the bestselling books were the euphemistically titled What Every Married Woman Should Know and What Every Married Man Should Know, which guided the reader in the ways of sexual health and enjoyment. What Every Married Woman Should Know instructed females on issues like menstruation, frequency of sexual intercourse, pregnancy, and menopause, while What Every Married Man Should Know reminded males that “the clitoris is the principal seat of erotic sensation in the female, but there are several other erotogenous zones which have a very definite sexual significance in stimulating sexual feeling.” In addition to the fact that such frank sexual instruction was hard to find in American libraries and bookstores of the 1920s, mail order lent a measure of anonymity in ordering titles such as A Hindu Book of Love (which excerpted the Kama Sutra) or Homosexuality in the Lives of the Great. Haldeman-Julius was fond of joking about the inevitable presence of titles like The Art of Kissing sandwiched into an order of philosophical essays and Physics Self-Taught titles, when the sex-themed book was “all the guy wanted in the first place.”

A couple decades later, when the Kinsey Report was grabbing headlines, Liberty magazine pointed out that the new sex study only underscored what the sales of Little Blue Books had always implied. “Sex outsells Shakespeare and everything else by about 10 to 1,” the article read. “And if the famous Kinsey Report on the sex life of the human male is now on the national best-seller list, Haldeman-Julius… can claim some of the credit for preparing the public to read about the forbidden fruit thirty years ago.”

While certain titles thus foreshadowed the sexual revolution, other Little Blue Books found their way into the hands of figures that would later influence the American civil rights movement. In “Proletarian Paperbacks,” Schocket noted that black activist and editor W. E. B. Du Bois “recommended the Little Blue Books in The Crisis, [and] they also became common tools of self-education and radicalization within African American communities. Langston Hughes and Claude McKay were strongly influenced in the 1920s, as were countless other, less famous activists.” In addition to promoting political progress in African-American communities, Little Blue Books targeted the complacency of their white American readership, noting, “We burn Negroes at the stake… fan into flame hatred and dissension, and then cover it all up with the solemn avowal that we are a Christian nation.” A few years after Haldeman-Julius published these words in a pamphlet called Is Progress an Illusion?, a number of high-profile lynchings moved him to assemble and publish the first anthology of African-American poetry to be widely distributed in the United States.

THE REQUISITE SCANDAL ERUPTS.

Given the scope and influence of Little Blue Books in the first half of the twentieth century, it’s easy to forget that the whole operation was based in a small town of a few thousand Kansans—many of whom did not care much for Haldeman-Julius. Even when the Appeal to Reason was in its heyday and American socialists regarded the town as a beacon of enlightenment, the majority of the people living in Girard were conservative (if tolerant) Republican Presbyterians. Had socialist publishing ventures not been such a stunning economic success in Girard, the likes of Emanuel Haldeman-Julius might have been less welcome. Nonetheless, the Philadelphia-born publisher came to enjoy life in the small prairie town. “In the East,” he wrote, “there is a greater spirit of personal liberty, free thought, and sophistication; but there is more stress laid upon social etiquette and what one shall wear. The reverse is true in Kansas. I do not mean to imply that one cannot live freely… but that what is pleasantly true of Kansas is the prevalence of a more easy, democratic social atmosphere.”

After the initial success of their publishing ventures, Haldeman-Julius and his wife, Marcet, moved into a sprawling white house (complete with backyard swimming pool) on a farm just outside Girard. Here they raised a son and a daughter, and entertained a steady stream of well-known guests, including Upton Sinclair, Clarence Darrow, Anna Louise Strong, and Will Durant (whose best-selling Story of Philosophy first appeared as a series of Little Blue Books). Though opinionated politically (he once referred to Hitler as a “mad homosexual” and Pope Pius XI as a “conceited and purblind ass”), Emanuel preferred light, witty conversation to intense socialist discourse. “I’m a radical, but I hate radicals,” he wrote. “I’d forget the revolution over a glass of wine.”

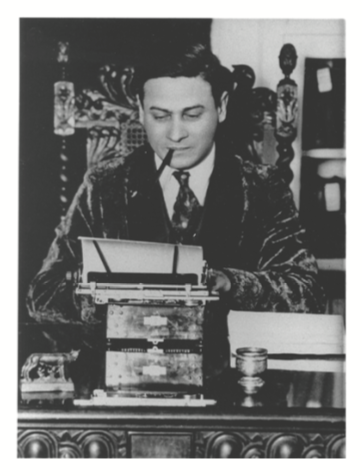

A cigar enthusiast, Haldeman-Julius rose each morning to smoke and sort through mail orders. He liked to note that Charlie Chaplin, Gloria Swanson, and Franklin P. Adams were regular customers—and when he received an order from a certain Haile Selassie of Abyssinia (grammar books, a rhyming dictionary, two crossword puzzle books, a joke book, and a copy of What Every Married Woman Should Know), he quipped that “the Lion of Judah reads practically the same kind of books which would appeal to an intelligent taxi driver, with a few sexology titles thrown in.” A true believer in mail order, he regularly shipped in seafood (ice-packed oysters, Rocky Mountain trout, Maine lobster), as well as practical items like socks and electric egg-incubators. Hatching chickens became a hobby for him at the printing plant, and his secretary later recounted how he would marvel “as though a great miracle had taken place right before his eyes” whenever a fluffy yellow chick burst out from its shell.

In addition to serving as vice president of the town bank, Marcet played an active role in the Haldeman-Julius publishing operation. She wrote a number of Little Blue Books, including What the Editor’s Wife Is Thinking About (later retitled Marcet Haldeman-Julius’s Intimate Notes on Her Husband). She also coedited and wrote for large-format magazines like the Haldeman-Julius Monthly (which at one point ran a Harry Houdini interview), and the American Freeman (which at one point ran a Billy Graham interview). In the early 1920s, the couple contributed short fiction to the Atlantic Monthly, and cowrote a prairie novel called Dust, which was well received by the East Coast literary establishment. (“Painfully gloomy as it is,” the New York Times noted, “Dust must be classed among the ‘big’ novels of the year”)

Despite this strong professional bond—and the storybook circumstances under which they first met—Haldeman-Julius and Marcet both suffered from alcoholism, and their marriage began to sour in the mid-1920s. A habitual womanizer, Emanuel enjoyed taking various female companions on weekend road trips in his custom-built, orange-wheeled Lincoln Coupe, checking in to Tulsa and Kansas City hotels under the name of “Lloyd Smith” (his assistant at the printing plant). Local gossip was not kind to the publisher, and his second wife would later recall how “town-folk got the idea he relished sex the way they relished a good cup of coffee.” Girard was further scandalized when Marcet fell into an affair with John Gunn, a Little Blue Book author who also did editing work for Emanuel. Eventually, Marcet threw her husband out of the house and moved Gunn in; Emanuel relocated to the printing plant, where he built himself a new studio and office. Their separation was exacerbated by the fact that Marcet had transferred the family assets to Emanuel after her breast-cancer surgery in 1925, and he proved deadbeat when it came to paying out her monthly allowance.

Throughout the 1920s, Haldeman-Julius took refuge from his domestic complications by traveling to Chicago and New York, where he met with colleagues and enjoyed a cosmopolitan respite from the isolation of the prairie. It was during a New York sojourn in October of 1929 that the stock market crashed, erasing most of the assets he and Marcet had accumulated in ten years of publishing. Returning to Girard, Haldeman-Julius put his orange-wheeled Lincoln into storage and resumed his work as the country sank deeper into the Great Depression. Times were tight for his publishing business; the foundering Little Blue Book franchise stores ceased operation, and the company introduced almost no new titles after 1931. The printing plant managed to keep most of its workers employed throughout the 1930s, however, thanks to a steady stream of mail orders for existing titles. Nationwide poverty, it seemed, had not affected Americans’ thirst for Little Blue Books.

Nationwide prosperity, ironically, would prove to be a different matter.

INSCRUTABLE MAYBE-SUICIDE NOTE

Emanuel Haldeman-Julius celebrated his sixty-second birthday the day before he drowned, in 1951. Marcet had died of cancer ten years previously (leaving the house to him), so it was his second wife, Sue, who found his naked body floating facedown in the backyard pool when she returned home from a visit to her mother. Inside the house, a note he’d left for her read: “If you want to insult a dog let me smell your highball.”

Given the events of the months and years leading up to that day, it’s tempting to speculate that foul play was involved. Though Haldeman-Julius had always cultivated enemies with his antireligious, anticorporate tracts, his series of articles linking the Vatican with the Axis powers during World War II provoked the Catholic Legion of Decency to mount a letter-writing campaign against him. Parochial-school classes around the country wrote angry postcards to magazines and newspapers, many of which stopped accepting Little Blue Book advertisements, or ran them only on the condition that atheist and socialist titles not be included on the list. Papers in Detroit and Philadelphia printed an ad for Little Blue Books that ran a day or two later with an editorial urging readers not to buy them. Undaunted, Haldeman-Julius commissioned an iconoclastic ex-priest named Joseph McCabe to write nearly fifty Little Blue Books between 1943 and 1947, including How an Ape Became a Man and How Christianity Grew Out of Paganism.

A more ominous confrontation came in 1948, when Haldeman-Julius published The FBI—The Basis of an American Police State: The Alarming Methods of J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover’s FBI responded with an investigation, and agents traveled to Girard to question the publisher in July of that year. Since the First Amendment affirmed Haldeman-Julius’s right to publish such materials, his printing operation was placed in the sights of the Internal Revenue Service, which sued him for $120,000 in unpaid taxes going back to 1945. As the court case dragged on, Emanuel’s drinking binges worsened and Sue noticed that he’d begun collecting information about Mexico, as if he was harboring plans of escape. In 1951 the court found him guilty of tax evasion, and he was fined $12,500 and sentenced to six months in jail—a ruling he immediately appealed.

Amid all this, a growing sense of cold war paranoia had skewed public sentiment against Haldeman-Julius. From the beginning, Little Blue Books had been matter-of-fact about printing controversial tracts alongside lighter fare (the Soviet Constitution and the Communist Manifesto were among the earliest volumes in the series); now, after three decades of peacefully propagating ideas, he was seen by many Americans as a threat to the nation. Responding to public attacks by Hearst columnist Westbrook Pegler, Haldeman-Julius asserted, “It is very sad that at this late date it is necessary to explain the difference between a Social Democrat and a Communist. I represent the true American tradition of radicalism; in fact, I am probably the last of the great American radicals.”

A few weeks after he wrote this, Haldeman-Julius was dead. The local coroner declared his death an “accidental drowning,” possibly brought on by a heart attack. When Sue drained the swimming pool some time later, she found smears and claw marks on the thin film of algae along the sidewalls, evidence of Emanuel’s failed struggle to pull himself out of the water. In 1954 his son Henry resumed the printing and sale of Little Blue Books on a part-time basis; though orders were slow in coming, no new titles were created, and the venture was hounded for ten years by an obscenity lawsuit regarding the mailing of sex manuals. (Henry ultimately won.) On July 4, 1978, in an incident blamed on stray fireworks, the Little Blue Book printing factory in Girard burned to the ground.

DEATH BY MATERIALISM

The fact that Emanuel Haldeman-Julius’s contribution to American culture was so quickly and widely forgotten was not just a matter of cold war prejudices. It was also the result of mass-media culture and the ascendancy of television; of unprecedented national prosperity and a political shift among the working classes; of the American tendency to disregard the recent past and continually reinvent self-perception. In many ways, it has been only in recent years, with the rise of the Internet, that we once again have a metaphor that helps us appreciate what Little Blue Books represented in their day.

In retrospect, postwar economic gains went a long way in diminishing popular interest in Little Blue Books. Whereas the notion of a “University in Print” once held a distinct appeal to those who weren’t in the position to go to college, tens of thousands of returned soldiers were now attending college on the G.I. Bill, creating a new American middle class. At the same time, increased material abundance affected all levels of American society, resulting in a gradual change in working-class politics. In his 1960 book The End of Ideology, sociologist Daniel Bell noted that “the workers, whose grievances were once the driving energy for social change, are more satisfied with the society than the intellectuals. The workers have not achieved utopia, but their expectations were less than those of the intellectuals, and the gains correspondingly larger.”

Meanwhile, the emergence of television sounded the final death knell of what media critic Neil Postman called “the Age of Exposition”—that time in American cultural life when the printed word dominated public discourse and “average Americans did not just think for themselves; they thought rationally about ideals, and they were able to express those ideals in a rational way.” By contrast, the ideals that filtered out from television screens were “simplistic, nonsubstantive, nonhistorical and noncontextual.” More information than ever was available to Americans, but it was reaching them in an idiom that placed little importance on nuance and broad perspective.

Thus, by the time a new generation came of age amid dramatic gains for feminism, civil rights, and sexual freedom, it was easy to forget that the mass promotion of those very causes had been normalized some forty years earlier by a Kansas publisher who, in rare moments of diminution, liked to describe himself as “a small-town printer who happens to think that ideas count.”