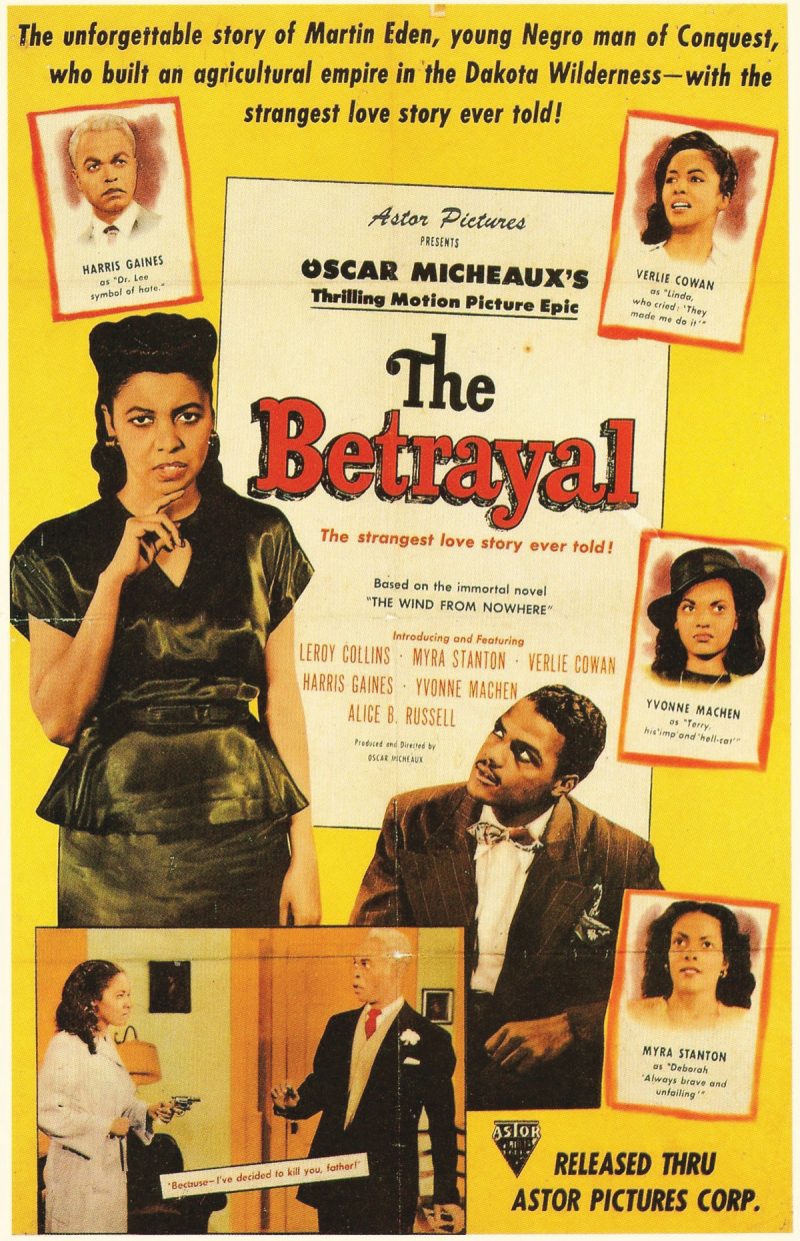

Between 1919 and 1948, only one of Oscar Micheaux’s films was ever reviewed in the New York Times. It was his last, The Betrayal (1948), and the anonymous critic dismissed it in two paragraphs as “consistently amateurish.” Three years later, the most prolific African American filmmaker of the twentieth century died, at age sixty-seven, penniless and forgotten. Of his approximately forty films (the exact number is uncertain), only fifteen still survive—all in battered, incomplete prints.

But as his work has been slowly rediscovered and restored—including major achievements like Within Our Gates (1920), The Symbol of the Unconquered (1920), Body and Soul (1925), and God’s Step Children (1938)—it is becoming increasingly clear that Oscar Micheaux was something unique. More than any other American filmmaker of the silent era, he tackled incendiary topics head-on, and his work was more achingly autobiographical than the films of any of his black colleagues, including Spencer Williams, George Randall, and Noble Johnson. More than just a filmmaker, Oscar Micheaux has become a symbolic figurehead of a body of as many as five hundred “race films” made between 1909 and 1950—films about black Americans, for black Americans, often made by black Americans.

Micheaux modeled his life after that of Booker T. Washington,

the African American educator who preached a philosophy of self-reliance for his race. He first used autobiographical novels as a forum to voice his Washingtonian philosophy, but when he discovered the populist appeal of cinema, he never looked back. At a time when the idea of an African-American filmmaker would have been inconceivable in the Hollywood studio system, Micheaux pursued filmmaking with zeal, abandoning any semblance of financial security in the process.

While Micheaux and his peers are slowly being reevaluated by critics and academics, they remain contentious figures at best. Their films are rarely shown, and their names are absent from popular film histories, like David Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary of Film and Mark Cousins’s The Story of Film (which states that African Americans were not allowed to make “good features” until the 1970s). Even those who do acknowledge their existence sometimes downplay their achievements, for reasons both aesthetic and political. Because even though Oscar Micheaux is often called the D. W. Griffith of black filmmaking, he is almost as frequently compared to Ed Wood.

*

In What Happened in the Tunnel (1903), a sixty-second short directed by Edwin S. Porter and released by the Edison Company, a man on a train makes a pass at a lady passenger. She gently strings him along, and he keeps flirting. As the train heads into a tunnel, he jumps forward to kiss her. Seven seconds later, when the light returns, the man discovers that he kissed the woman’s black maid by mistake. He panics, curses, and rushes back to his newspaper while both women laugh.

Unless used for a cruel joke, race was generally ignored in the first decades of American cinema.

When black characters were depicted, they were comic buffoons played by white actors in blackface, like in the Mack Sennett comedy Colored Villainy (1915), or A Nigger in the Woodpile (1904). The occasional “serious” works were little better: in Thomas Edison’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1903), blackfaced whites knelt and cried for their massahs in front of the camera, while genuine black performers milled about in the distance. The most notorious exception was D. W. Griffith and Thomas Dixon’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), which famously blamed the failures of Reconstruction on an unruly black populace.

A handful of proto-race movies predate Griffith’s film, though. A Fool and His Money (1912), directed by French expat Alice Guy-Blaché, featured an all-black cast and was marketed to black audiences. The Railroad Porter (1913), a comedy in the Keystone Kops vein, became the first film by a black director, William Foster. A writer for the Chicago Defender, Foster was early to recognize cinema’s power to influence, and dreamed of building his own studio to produce positive race-themed films. “Our brother white is born blind and unwilling to see the finer aspects and qualities of American Negro life,” he wrote in 1913. But it was the indignity of The Birth of a Nation that triggered the first film companies owned and operated by African Americans.

The year 1916 saw the launch of the Frederick Douglass Film Company, whose first production, The Colored American Winning His Suit, was advertised as an attempt to “offset the evil effects of certain photoplays that have libeled the Negro and criticized his friends.” Before folding, the company completed two more films about noble black men, The Scapegoat (1917) and Heroic Negro Soldiers of the World War (1919). In 1918, the Photoplay Corporation mounted The Birth of a Race, an ambitious rebuttal to Griffith conceived by Booker T. Washington and his secretary, Emmett J. Scott. In the fragments that survive, the film frames the history of mankind as an ongoing struggle of man against man, from Adam through Noah, Moses, Christ, Lincoln, and the First World War. In every era, God’s message of brotherly love and equality is thwarted. “Among the vast throng that listened were men of all races,” reads one title card. “But Christ made no distinction between them—His teachings were for all.” This expensive production was a major flop, but it was daring in its unabashedly pro-integration message.

While these films were in production, Oscar Micheaux was traveling the country as a self-styled success story, selling novels about his exploits. He was born in Metropolis, Illinois, in 1884, the son of former Kentucky slaves who migrated north after the Civil War. In his early years, he worked odd jobs and did manual labor, including a stint as a Pullman porter, while saving enough money to buy land in South Dakota. As the state’s “only colored homesteader,” Micheaux gradually won the respect of his white peers, and wrote about his triumphs in two semiautobiographical books.

Micheaux’s 1913 book, The Conquest, written in a voice similar to Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery, combines frontier adventure with the author’s personal philosophy for the advancement of the race. The first-person novel chronicles the adventures of one Oscar Devereaux (“which, of course, is not my real name, but we will call it that for this sketch”), an ex–Pullman porter who, like Micheaux, buys a farm in South Dakota and builds an empire. Washington’s name is frequently invoked as a symbol of progressive black leadership: in “The Progressives and the Reactionaries,” chapter 37 of The Conquest, Micheaux writes:

The Progressives, led by Booker T. Washington and with industrial education as the material idea, are good, active citizens; while the other class distinctly reactionary in every way, contend for more equal rights, privileges, and protection, which is all very logical, indeed, but they do not substantiate their demands, with any concrete policies; depending largely on loud demands, and are too much given to the condemnation of the entire white race for the depredations of the few.

He goes on to “deplore the negligence of the colored race in America” for not “seizing the opportunity” to secure and harvest farmland in the American Northwest. The villain of the book is Devereaux’s father-in-law, a reverend depicted as arrogant and power hungry, and opposed to the education and integration of his race. He was the first of many regressive religious leaders to appear in Micheaux’s books and films.

The Homesteader was a longer (533 pages), more melodramatic rewrite of The Conquest. Once again, an ambitious black farmer (Jean Baptiste) overcomes trials and tribulations, including a failed marriage and regressive minister father-in-law, to become the first great “Negro pioneer.” As in The Conquest, the Micheaux surrogate falls hopelessly in love with a white woman, but in a new twist it is revealed that she has black lineage, and their relationship can be consummated. Light-skinned black characters “passing” as white would become one of Micheaux’s most persistent motifs.

The Homesteader caught the attention of George and Noble Johnson, brothers whose Lincoln Motion Picture Company briefly succeeded where the other black studios failed. Noble Johnson was the first black performer to achieve something resembling star status, and his presence helped George Johnson reach distribution deals with regional theaters. Beginning with The Realization of a Negro’s Ambition (1916), the Johnsons enjoyed moderate but consistent success with a series of films about black men fighting for social justice. The Homesteader (1919) was to be the company’s first feature-length production, but the untested Micheaux insisted on directing the eight-reel film himself, and the deal collapsed. Instead, after raising money from private investors, Micheaux wrote, produced, and directed what would become the first feature-length film ever made by an African American.

Micheaux distributed the film himself, embarking on the first of his many nationwide tours of black neighborhoods which would earn him a P. T. Barnum–esque reputation. The film’s frank treatment of religion and miscegenation led to battles with censor boards and curiosity from audiences, who had never encountered a film that dealt with such topics from a black point of view. His years selling novels had already made him a master of ballyhoo: The Homesteader was advertised as “destined to mark a new epoch in achievements of the Darker Races!” The film was immediately greeted as a landmark by the black press, and became such a box-office success from city to city that all available prints were essentially played into deterioration. Its success fueled a boom in race-movie production.

*

Around 90 percent of silent films are lost forever. For independent filmmakers, without resources to preserve their few prints, the numbers are especially grim. The heartbreaking thing about studying race movies is how few films survive from the movement’s peak years, in the early 1920s. Over time, Oscar Micheaux’s output in the silent era—somewhere between twenty-one and twenty-five films—has dwindled to only three extant works.

Still, from these three films, we can draw some conclusions about his artistic mission. Like other black filmmakers of the time, Micheaux’s values were firmly middle-class. He saw film as a soapbox to “uplift the race,” and to promote images of black entrepreneurs over gamblers, criminals, and alcoholics. But unlike that of his contemporaries, his social criticism extended beyond his race: none of the other race filmmakers dealt with segregation, miscegenation, “passing,” corrupt preachers, substance abuse, rape, and the Ku Klux Klan so frequently and so powerfully. His surviving silent films are the greatest race movies we still have.

Body and Soul is the most technically polished Micheaux film available, with a memorable storm sequence and a charismatic debut performance by actor/singer Paul Robeson. He stars as an escaped convict who hides in a Southern town under the guise of a preacher, using the persona to steal money from his gullible followers. Those who recognize him as an alcoholic, womanizing fraud find themselves socially ostracized. The film stirs memories of The Conquest, where Micheaux wrote of his reverend father-in-law, “I was becoming more and more convinced that he belonged to the class of the negro race that desires ease, privilege, freedom, position and luxury without any great material effort on their part to acquire it.”

The Symbol of the Unconquered (1920) is a thick stew of racial anxiety. Its hero is Hugh Van Allen, a black homesteader hopelessly in love with a light-skinned woman passing for white. Van Allen runs afoul of Jefferson Driscoll, a light-skinned crime boss whose rejection by a white woman led him to renounce his heritage. When Driscoll discovers Van Allen’s homestead is above an oil field, racial self-loathing supplements his greed.

“He will capitulate or I will subject him to such a treatment that he’ll either go crazy or die,” Driscoll tells his henchmen. One of the group responds, “…and what is this treatment?” The screen goes black, and a tiny flame appears; it becomes larger as it moves closer to the camera, illuminating a white-hooded man on a horse, who quickly rides off into the darkness. It’s an image that sears a permanent imprint in your retinas.

And then there is Within Our Gates, the best and most upsetting of all race movies. The story follows Sylvia, a mixed-race Southern woman who tries to raise money for an all-black schoolhouse run by a kindly reverend. While searching for funds in the North, she encounters Mrs. Warwick, a white philanthropist sympathetic to her plight. Mrs. Warwick’s Southern friend Geraldine protests. “Lumberjacks and field hands. Let me tell you—it is an error to try and educate them,” she says. To her appalled friend, Geraldine instead suggests the money be given to “the best colored preacher in the world,” Old Ned, who “will do more to keep Negroes in their place than all your schools put together.”

Old Ned (who, pointedly, the intertitles never call “reverend”) is the saddest of Micheaux’s regressive preachers, accepting money from the white elite on the condition that he keep black churchgoers from challenging the status quo. To his congregation he delivers sermons about how white people’s wealth will lead to sin and hellfire; to the local whites, he is smiley and buffoonish: “White folks is mighty fine!” In private, he hates himself, and believes he will go to hell. “Again I’ve sold my birthright… Negroes and whites—all are equal.”

In a flashback, we meet Efram, the Uncle Tom–ish servant of Sylvia’s childhood landlord, who falsely accused Sylvia’s father of murdering his master.

Efram is happy to shun and betray his race if it means hobnobbing with whites. While Sylvia’s family hides to escape lynching, Efram joins the lynch mob in a clearing. Suddenly, he is struck by a frightening image: Micheaux fades to a shot of Efram hanging from a tree, his eyes wide open, his tongue sticking out pathetically. Micheaux does nothing to sugarcoat the image; if anything, actor E. G. Tatum’s facial expression renders it horribly comic.

Of Micheaux’s surviving films, Within Our Gates is the only one to feature a substantial number of ignorant or sinister white characters. That Micheaux’s publicity materials called Efram “a white fo’kes nigger” suggests that most of his scorn was aimed at traitors within his own race. The black race could be uplifted, Micheaux implied, but it shouldn’t seek or expect any help from whites.

*

A surprising characteristic of most race movies of the era is that, unlike Micheaux’s films, they almost completely ignore the social inequalities of the time. George Randol’s Midnight Shadow (1939) opens with the following text scrawl: “In the southern part of our country, lies that great land of romance and sunshine, known as the Old South.” It continues, “Here amid fertile fields, vast areas of timber, oil lands and rippling rivers… these people of darker hue have demonstrated their abilities in self-government by the orderly processes of law of which they are capable when unhampered by outside influences.” Needless to say, this idyllic community would have been a fantasy world in the Deep South of 1939. Instead, there were black comedies, westerns, musicals, and melodramas, all mimicking the conventions of the glossy studio productions of the day. Audiences who saw an all-black gangster movie like Underworld or Dark Manhattan (both from 1937) saw the glittering nightclubs, penthouse apartments, mink coats, and tough-talking hoods of a Jimmy Cagney film for Warner Bros.

Segregated theaters in the South were the most dependable market for race movies, and, for these audiences, cities like New York and Chicago were depicted as black meccas, where African Americans wore expensive suits and lived in comfortable middle-class apartments. Edgar G. Ulmer’s Moon Over Harlem (1939) opens with a gorgeous montage of nocturnal Harlem street scenes as glamorous, in their way, as the vistas that open Midnight in Paris. Some race movies have gained a documentary interest over time, almost by accident. Musicals like Darktown Revue (1931), Juke Joint (1947), and the Cotton Club–set Cab Calloway vehicle Hi De Ho (1937) preserve the work of black musicians and vaudevillians who would otherwise have been forgotten. The short film St. Louis Blues (1929) features the only film appearance of Bessie Smith, the legendary singer whose searing voice earned her the nickname “Empress of the Blues.” Some, especially Oscar Micheaux, padded their films with small-time dancers, crooners, and jazz bands who would work for free.

While race movies mostly ignored the realities of Jim Crow and segregation, many of the most popular films took a critical look at the black community itself. Consider Spencer Williams’s The Blood of Jesus (1941)—a church-basement staple, and the first race movie to be added to the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry. In this Southern-set drama, a virtuous woman is accidentally shot by her no-account husband, and before ascending to heaven, she is tempted to a life of sin in the city. This unabashedly moralistic film takes a literal God’s-eye view of the gamblers, pimps, and dance-hall girls who it implied were holding back the race.

Micheaux’s and Williams’s films were about advancing the race past these moral degenerates, but a lurid melodrama called The Scar of Shame (1929) was totally pessimistic. It follows a lower-class girl who flees from an abusive family to marry into an upper-class family but is looked down upon by her mother-in-law. Soon she is facially disfigured in the crossfire of a gunfight between her husband and her father’s gambling friend. With her husband in jail, she is forced into a life of prostitution. When her husband escapes, he rejects her, and she commits suicide. There is nothing hopeful about this film: unlike other race movies, it shows class barriers to be insurmountable obstacles.

Oscar Micheaux never could have made The Scar of Shame—he was too doggedly persistent. He battled with state censors, sometimes pretending to cut controversial material but screening his uncut versions anyway (one of his lost films, The Deceit [1923], is about a black filmmaker who struggles with narrow-minded censors). Some of his films were popular, but prints, advertising, staff, office space, and travel ate up any modest profits. He was always drowning in debt and buried in lawsuits from unpaid cast, crew, and creditors. He was in such dire straits that for a time all his work was banned in Harlem and Virginia (for unpaid debts to theater operators?). And still, as he was in the midst of bankruptcy proceedings in 1928, he had two films in production (The Broken Violin and Thirty Years Later, both now lost). He became the first black filmmaker to direct a talkie (The Exile, 1931), and the only one to transition from silence to sound. Jean Baptiste and Oscar Devereaux triumphed over adversity; so would Oscar Micheaux.

*

Although 1920 and 1921 were the most productive years of race-movie production, even at their peak only 121 segregated theaters in the United States catered to the market. Of the dozens of black film companies that emerged, most collapsed after one movie. Competition also came from white producers and directors, who founded their own companies to distribute films for black audiences as early as The Homesteader’s success. Some of these films were entertaining, but none were ambitious.

The Black King (1932), directed by Bud Pollard, was a poor satire of Marcus Garvey, the writer and activist who led a failed “Back to Africa” movement in the ’20s. In the film, “Charcoal Johnson” is a false preacher who leads a similar movement in his congregation, using his fervor as a front to embezzle money and seduce women. The film’s white director made several other fraudulent race movies, including Big Timers (1945), a vehicle for the ever-controversial Stepin Fetchit.

A few black filmmakers used white money to their advantage. Herb Jeffries, a mixed-race crooner, starred in a trio of all-black westerns as Bob Blake, a singing cowboy—Two-Gun Man from Harlem (1938), The Bronze Buckaroo (1939), and Harlem Rides the Range (1939). He received financing from Jed Buell, who specialized in novelties like the little-people western The Terror of Tiny Town (1938), but Jeffries was no freak show. His smooth, charismatic performances were equal parts Gene Autry, Hopalong Cassidy, and Clark Gable. “In those days, my driving force was being a hero to children who didn’t have any heroes to identify with,” Jeffries said years later. “I felt that dark-skinned children could identify with me and, in The Bronze Buckaroo, they could

have a hero.”

The supporting casts feature a who’s-who of Hollywood’s black character actors. There was Spencer Williams, director of The Blood of Jesus, but better known as Andy on TV’s The Amos ’n Andy Show. There was Mantan Moreland, a comedian famous for his demeaning role in the Charlie Chan series (Spike Lee used his name for one of the neo-blackface characters in Bamboozled). Matthew Beard, the little boy who idolizes Jeffries, was “Stymie” in the Our Gang comedies. “We knew even then that ‘Stymie’ was an insult to our race,” Beard recalled years later. “But it was the Depression and I had seven sisters and six brothers at home.” The Bronze Buckaroo westerns sometimes feel like they were made in a studio-era bizarro world where the bit-players and comedy relief have taken over the means of production.

With the dawn of sound, Hollywood studios began making short subjects with black entertainers, like the Warner/Vitaphone The Black Network (1936). Every once in a while, they dabbled in an all-black musical, like Vincente Minnelli’s Cabin in the Sky (1943). More commonly, black culture was condescended to, as in the “All God’s Chillun Got Rhythm” number in A Day at the Races (1937), where black children chirp, “Who’s that man? It’s Gabriel!” at a flute-playing Harpo Marx. When MGM released the first all-black-cast musical, Hallelujah! (1929), its star, William Fountaine, had already starred in four Micheaux films. In Oscar Micheaux: The Great and Only, Patrick McGilligan cites an MGM press release that claimed he was “discovered on the street” by director King Vidor.

The Lincoln Motion Picture Company suffered a fatal blow when its main star, Noble Johnson, took a contract with Universal. Blink and you’ll miss him as the Native Chief in King Kong. Other companies collapsed when the market for race movies declined in the late ’20s. With some exceptions, black filmmakers were behind few of the race movies of the ’30s and ’40s.

*

The only surviving print of The Symbol of the Unconquered was discovered in Belgium in the ’90s. Within Our Gates disappeared until 1990. With so much of his best work unavailable for decades, only Micheaux’s reputation as a showman survived—especially his hyperbolic advertising, with actors billed as “the black Valentino” or “the sepia Mae West.” When he was cited in the decades following his death, it was more as a cultural curio than as an artist, and his sound films—where his racial psychodrama grew more acidic and his product-ion values more impoverished—were ripe for ironic reading.

The critic J. Hoberman helped bring Oscar Micheaux to mainstream attention with his 1980 essay “Bad Movies,” which contains some of the most perceptive and discomfiting analysis ever written about the director. Written as a response to the early-’80s bad-movie craze (launched by Harry and Michael Medved’s book The Golden Turkey Awards), Hoberman’s article considers the disparity between a “bad” movie’s aspirations and its impoverished mise-en-scène, celebrating the sublime naïveté that results. His point of entry is Edward D. Wood Jr., whose Plan 9 from Outer Space is a memorably shoddy facsimile of a Hollywood science-fiction film. In contrast to the safe, likable badness of Wood, Hoberman offers Micheaux as a filmmaker “whose anti-masterpieces are so profoundly troubling and whose weltanschauung is so devastating that neither the Medveds nor the World’s Worst Film Festival are equipped to deal with him.”

Hoberman saw poetry in the objective badness of Micheaux’s post-1928 technique—how at their worst his films seem like grotesque parodies of Hollywood melodramas. In later Micheaux productions, his actors speak in halting dictions while library music drones listlessly on the soundtrack. Editing is choppy, continuity is nonexistent, and sets reappear over and over, only slightly redecorated. At times, his work borders on surrealism: about half of Ten Minutes to Live (1932) was shot with sound, the rest was shot silent (with intertitles) to save money, but no attempt was made to smooth the transitions. Hoberman wrote, “Micheaux’s films are so devastatingly bad that he can only be considered alongside Georges Méliès, D. W. Griffith, Dziga Vertov, Stan Brakhage, and Jean-Luc Godard as one of the medium’s major formal innovators.”

But in Hoberman’s analysis, what really separates Micheaux from Ed Wood are his sometimes-painful racial politics. “Trapped in a ghetto, but unwilling or unable to directly confront America’s racism, Micheaux displaced his rage on his own people,” Hoberman wrote. “Hence his horrified fascination with miscegenation and ‘passing,’ his heedless blaming of the victim, his cruel baiting of fellow blacks.”

It is true that his work displays a preoccupation with interracial longing that is disturbing in its persistence. In The Conquest and The Homesteader, Micheaux wrote that during his days in South Dakota, he fell in love with a white woman. He kissed her, apparently, but nothing more, and he never saw her again. Micheaux’s biographers believe the rejection haunted him for the rest of his life. In The Exile (1931), another film about a black homesteader, the hero leaves his farm for the city to escape an unrequited interracial love. In the final scenes, it is discovered that the woman has Ethiopian heritage, and, thanks to this technicality, they can pursue their love. Similar discoveries are made at the end of The Symbol of the Unconquered, The Betrayal, and other Micheaux films.

The Symbol of the Unconquered begins with a painful scene where the light-skinned Van Driscoll is outed by his mother as a black man while he’s wooing a white woman. When the woman rejects him, he disowns his mother and his race. He is the villain of the piece, but his plight is similar to that of the film’s hero, who also loves across racial lines. The hero and the villain represent two strategies for coping in a racist society: one tries to advance his race and transcend its boundaries, the other tries to reject it entirely. Micheaux seems to empathize with both approaches. No filmmaker worked harder to transcend racial borders than Micheaux, and no filmmaker depicted those borders as more arbitrary.

The most successful race-themed studio film of the ’30s was Imitation of Life (1934), about a mixed-race woman who passes for white. This was the topic that Oscar Micheaux returned to most compulsively, and Imitation of Life provided the impetus for his remarkable late work, God’s Step Children. If Micheaux is really guilty of “heedless blaming of the victim” and “cruel baiting of fellow blacks,” then this fascinating film is where the charges derive.

In the opening scenes, Mrs. Saunders (Alice B. Russell, Micheaux’s wife), a kindly black widow, adopts a mixed-race infant from a mysterious woman. The infant, Naomi, grows into a cruel problem-child who shuns her black schoolmates, sneaks off to the “white school,” and spreads malicious rumors about a schoolteacher. Her behavior becomes so deplorable that she is sent to a convent for ten years.

In the intervening decade, her brother, Jimmie, has become a well-to-do entrepreneur with plans of starting a homestead. Back from the convent, Naomi falls in love with him, but settles into a marriage with a darker-skinned black man, whom she hates for his physical features. When the marriage fails, Naomi tells Mrs. Saunders she is “leaving the Negro race” to live the rest of her life as a white woman. Why does Naomi suddenly disown her ethnicity? In Micheaux’s original cut, she was reportedly more explicit in her hatred; in the censored version, her self-loathing is all the more disturbing for being so elliptical.

Jimmie is Micheaux’s surrogate—a Pullman porter turned homesteader who dreams of shepherding his wayward race. His girlfriend says that most black people get into the gambling racket, and wonders, “Why can’t they go into some legitimate business like white people?”

“They could,” says Jimmie, “but they’ve made no study of economics. Their access is to take the line of least resistance. The Negro hates to think; he’s a stranger to planning… After viewing the failure of our group—and we are failures—it seems we should go right back to the beginning, start all over again.” This kind of criticism was familiar from Micheaux, but never had it seemed quite so bitter, and never had it come from a film this sour.

By this point, Micheaux’s autobiographical tendencies were more poignant than inspirational. Jimmie is a young dynamo like The Conquest’s Oscar Devereaux, eager to change the world and his race through sheer force of will. For Micheaux, such dreams were in the past. After his bankruptcy, in 1928, Micheaux could no longer afford to finance his own projects, and worked for Alfred N. Sack, a Jewish entrepreneur. Micheaux resented the white producers who crowded the race market in the ’20s, but Sack Amusement Enterprises owned a string of black theaters in the South, and offered measly but reliable financing. By the ’40s, Sack would be the only producer offering consistent employment to a black director—Spencer Williams churned out a string of sin-and-salvation dramas like Go Down, Death! (1944) and Dirty Gertie from Harlem U.S.A. (1946) for Sack’s Southern theaters.

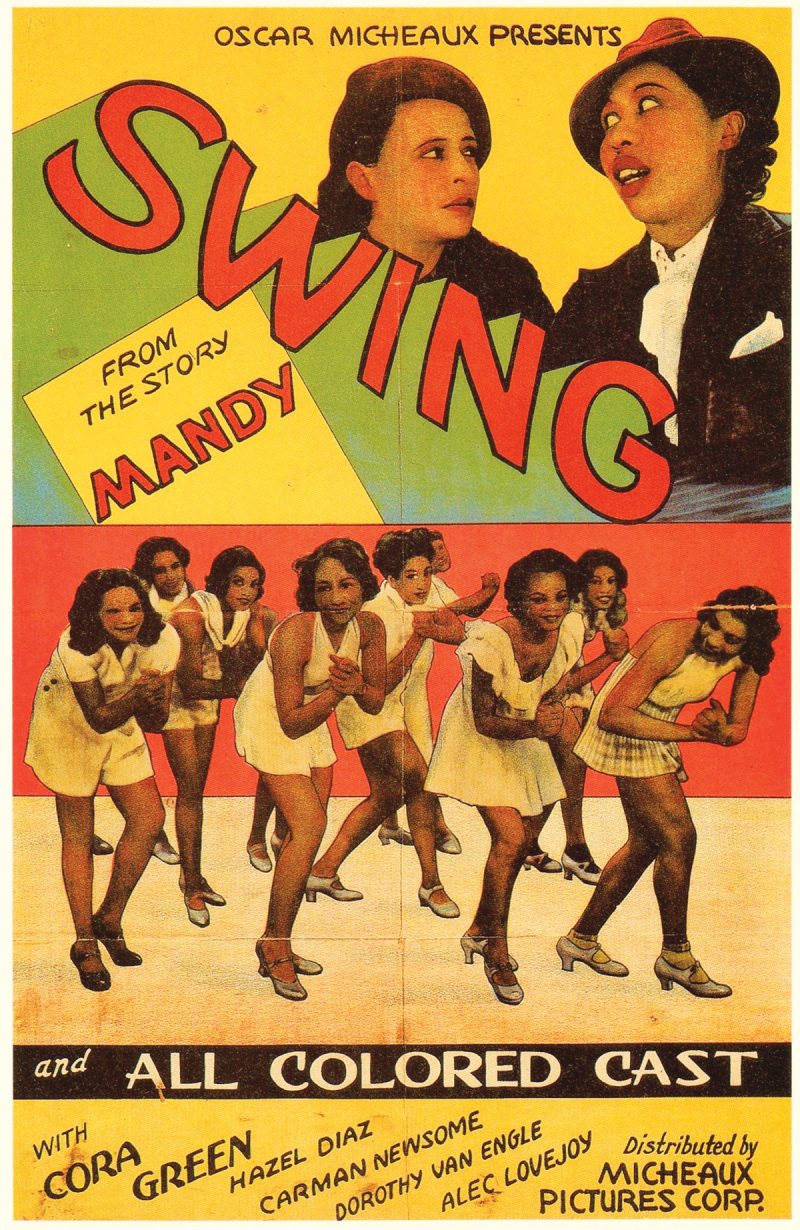

In Swing! (1938), a fluffy Micheaux/Sack production, a Harlem theater director announces a deal to bring his all-black musical to Broadway. One can sense Micheaux’s wounded pride in the director’s boast: “Of all the Colored shows that have gone by the boards, no Negro has ever produced one. From Williams and Walker to The Green Pastures, they’ve all been sponsored by white men. No Negro has ever been in on the money, or the profits!”

*

When his relationship with Sack ended, in 1940, Micheaux returned to selling novels, and eventually raised the money for one last crypto-biopic. The Betrayal (1948) was his first film in eight years, and mainstream reviewers, unfamiliar with Micheaux’s earlier work, dismissed the film as static, amateurish, and punishingly long. The black press was little kinder. The times had passed him by.

Even among Micheaux films, the disappearance of The Betrayal is deeply unfortunate—the three-hour epic sounds like Oscar Micheaux’s summative achievement. The New York Times review describes its protagonist as “an enterprising young Negro who develops an agricultural empire,” with a story involving “the relationship between Negroes and whites as members of the community as well as partners in marriage.” All of these topics had become so familiar in his body of work that they verged uncomfortably into obsession.

The Betrayal would become Micheaux’s last film—its total critical and commercial failure destroyed him, personally and professionally. He never became Jean Baptiste or Oscar Devereaux, no matter what he wrote. The years took their toll, and the era of race movies was over for good by 1951, when its greatest practitioner died of heart failure. His widow burned his business papers and threw out all the film prints in his collection, and we only know his work thanks to decades of rediscovery and restoration of a fraction of his catalog.

Was Oscar Micheaux “the Jackie Robinson of film,” as one biographer has claimed? He was the first black filmmaker to sustain a long career on his own terms, and the first to make great and important films. But his career, like his films, resists a clean, redemptive arc. The power of his early work gave way to the frustration and hostility of God’s Step Children, and his desire to uplift his race gave way to anger at his race for being too slow to be uplifted. Micheaux may have been angry at himself because he was never able to become “Jean Baptiste” or “Oscar Devereux.” But his work is important because he was Oscar Micheaux.