If you’re sitting in an American diner that happens to have any predilection for nostalgia—and it’s extremely rare that any diner does not—there’s a good chance you’re going to see a certain painting somewhere inside the establishment. It’s a series of paintings, actually, but they will have one thing in common, whether the setting is a casino, a gas station, a movie theater, or a pool hall: they will always portray four specific people: Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, and Humphrey Bogart.

In one painting, titled Classic Interlude, Monroe and Presley sit happily together at the cinema as James Dean slouches in the row in front of them, too cool to care that he’s not on a date with Marilyn, tossing a kernel of popcorn up into the air. But his gaze back toward the pair betrays his whatever-veneer. There’s no mistaking it: he wishes he was Elvis, cozied up next to the beautiful woman with the million-dollar smile. Meanwhile, here comes Humphrey Bogart, ambling down the theater aisle, a flashlight pointed toward the trio’s seats. Perhaps Dean, always the rebel, didn’t pay for a ticket.

Another tableau depicts the outside of a drive-in restaurant. Presley sits on the back bumper of a car, banging out a song on an acoustic guitar. Monroe appears to be swept away by the tune; Dean eyes Presley half with contempt, half with envy. Meanwhile, Bogie stares off into the middle distance with the intensity of a man who has lived more life than he has left in front of him, much of it marked by regret. It’s always some semblance of this dynamic with the four: a love triangle, plus an older man who oversees, chaperones, or is trapped in his own inner world in proximity to their young(ish) romance.

These four American celebrities never appeared in a movie together. None of them were good friends. There are stray stories of their lives briefly intersecting, but nothing consequential. All three of the men met Monroe and, of course, all three were rumored to have had a fling with her. Two of them died in the 1950s; Monroe in the ’60s; Presley in ’77, at the age of forty-two. Most of them reached the height of their fame in the 1950s, though Bogart’s star certainly shone brightest in the ’40s, when he made such movies as The Maltese Falcon, Casablanca, and The Big Sleep.

In other words, this isn’t the most obvious foursome to occupy a painted, nostalgic eternity together. But now, ironically, thanks to these ubiquitous paintings, Monroe, Dean, Presley, and Bogart seem forever inseparable. So who decided on this grouping, and why? The answer is comically, unnecessarily complex. It begins with an impressionist painter from New York who created one of the great odes to American loneliness in the early 1940s.

Edward Hopper was born in Nyack, New York, in 1882, the son of a dry-goods merchant and a woman whose love of art led to her son’s initial interest in painting. Elizabeth encouraged Edward’s pursuit of the craft, even hand-selecting the boardinghouse where he resided during his first trip to Paris, in 1906, to study the masters. After Hopper spent six years at New York School of Art,[1] his work—etchings, watercolors, and then oil paintings—began to develop its own style.

He was an impressionist, initially in the style of Degas and Manet, who ignored modern movements, even audaciously claiming never to have heard the name Picasso mentioned during his visits to Europe. By the time Hopper’s point of view was fully formed, he had figured out how to capture the mood of noir cinema in his city scenes, with or without people inhabiting them. But instead of the stark black-and-white tones of the silver screen, he made his scenes work with saturated colors.[2] In Hopper’s hands, the most mundane tableau is imbued with a deep mystery, and a sense that something unusually intense is about to happen, or just has.

For nearly two decades after his schooling, Hopper made a living creating commercial illustrations—a job he passionately disliked—while his serious work was largely ignored by the art market. But right around the time he reconnected with his old classmate and future wife, Josephine Nivison,[3] at an artists’ colony in Gloucester, Massachusetts, his career took a turn for the better—much better. In 1933, he enjoyed his first major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. By the close of the decade, he was among the most successful living American artists, right on the cusp of creating his finest masterpiece.

Hopper was fifty-nine when he began working on Nighthawks, just as the country formally entered World War II. His lauded position in the art world had been well-earned, due not only to his unwavering work ethic but also to his refusal to conform to trends that might lead to higher asking prices for his work. He later remarked that he based his most famous painting’s setting on an all-night lunch counter he’d observed on Greenwich Avenue in Manhattan, two miles from his apartment.[4]

Routinely cited as one of the most recognizable American paintings of all time, Nighthawks presents an illuminated diner at the intersection of two desolate, darkened streets, with a man and woman sitting stoically inside. The unmistakable emotional distance between them could be decades in the making, or they could have met earlier that night. A blond male employee in a crisp white hat tends to something unseen just below the counter, while another well-dressed customer with his back to us hunches over his late-night cup of joe. There is one unifying mood that looms over the entire scene: loneliness. Gordon Theisen’s book-length meditation on the painting, Staying Up Much Too Late: Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks and the Dark Side of the American Psyche, called it a “twentieth-century masterpiece… a deeply cold and alien work, despite its immediately recognizable subject matter,” one that “exerts a seductive pull.”

While Hopper was dubbed “the visual bard of American solitude” by The New Yorker in 2020, and received countless variants of this sentiment over the years, he never intentionally set out to capture Americans’ unique, shared feelings of separateness. But in his artistic quest to express his own inner loneliness,[5] he accidentally bottled a zeitgeist. “I don’t think I ever tried to paint the American scene,” Hopper once explained; “I am trying to paint myself.” Just as everyone in a dream is some representation of the dreamer, according to Jungian theory, every figure in Nighthawks is Hopper.

In 1942, the Art Institute of Chicago purchased the painting for three thousand dollars, and it has resided there ever since. Nighthawks’s influence was immediate and long-lasting. In 1946, director Robert Siodmak clearly re-created the painting in the opening scene of his film The Killers, an adaptation of the Ernest Hemingway 1921 short story, which in turn had been one of the inspirations for Nighthawks—a perfect loop of influence. Later, Alfred Hitchcock unabashedly re-created Hopper’s House by the Railroad (1925) as the ominous setting for his 1960 masterpiece, Psycho. Knowing the director’s appreciation of Hopper’s eye, it’s hard to watch 1954’s Rear Window without feeling as if each glimpse into each apartment owes a heavy nod to the voyeuristic point of view we encounter in paintings like Nighthawks and 1928’s Night Windows. From there, the painter’s influence on film grew exponentially, to a point where it’s hard to differentiate between direct influence and the influence of influence. Countless cinematographers and directors—Abraham Polonsky, George Barnes, Gordon Willis, Wim Wenders, and David Lynch, to name a few—have referenced Hopper explicitly and tacitly in their work. On it went, with artists from musician Tom Waits to writer Joyce Carol Oates drawing on Nighthawks for their output.

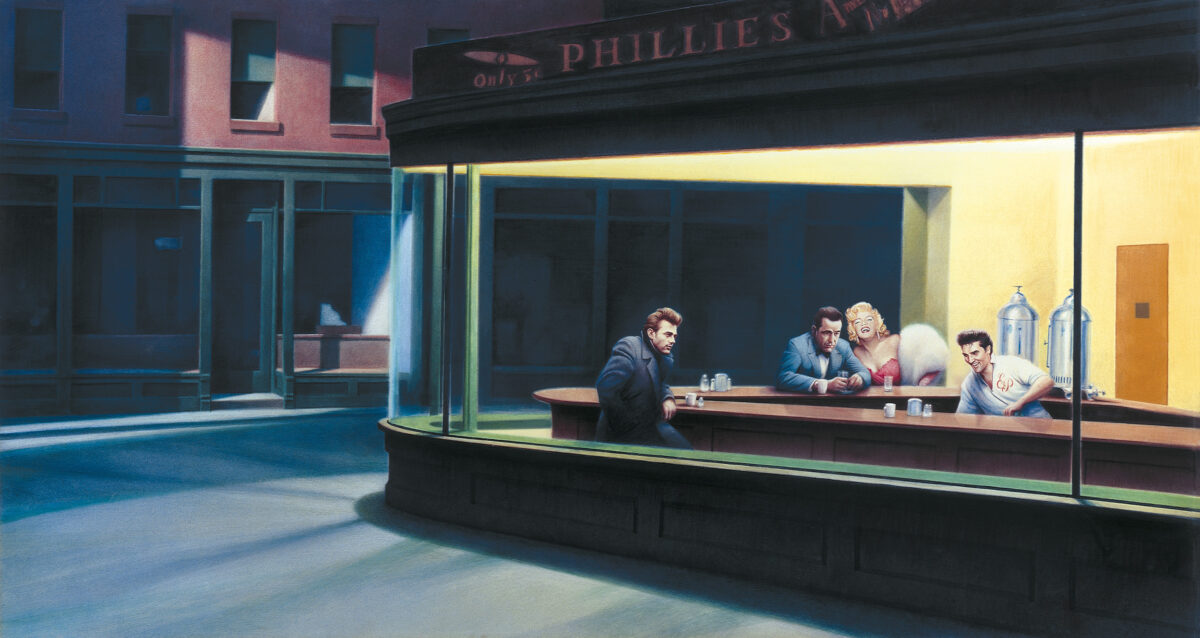

Then, in 1985, something very strange happened in the Nighthawks chronicle: an intense Austrian Irish artist named Gottfried Helnwein, fresh off creating the horror-shock cover of the 1982 Scorpions album Blackout, painted Boulevard of Broken Dreams.[6] Boulevard is an extremely faithful re-creation of Hopper’s Nighthawks setting, except that Helnwein replaced the four anonymous figures with Elvis Presley (as the diner employee), Marilyn Monroe (one-half of the seated couple, here gleeful), Humphrey Bogart (the only figure who maintains the same mood as the original figure he’s standing in for), and James Dean (as the loner, here staring wistfully at Elvis’s dumb joy in doing menial service work).

If the visual mash-up was meant as a biting commentary on Hopper, or on American celebrity, or both, it misses the mark, but in doing so, ironically, it became massively popular.[7] In 1994, in a piece about the persistent influence of Hopper’s work, The New York Times noted how the parody painting had become a “best-selling poster… a favorite from Brooklyn pizza parlors to California shopping malls.” Journalist Tim Foster described it as “the absolute epitome of kitsch—a work so godawful that it’s hard to actually think of it as anything other than ‘product.’” Foster is, as far as I can tell, the only reporter ever to get a quote from Helnwein on the work. (Multiple interview requests went unanswered for this piece.) The writer of an otherwise praise-laden profile of the artist in 2011 notes:

I did the mental equivalent of a spit-take when I realized that Helnwein had painted Boulevard of Broken Dreams, the all-too-familiar parody of Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks… The artist fumbled uncomfortably when I asked him about the painting. “That was meant as a joke… it got a life of its own and it got so big—that was not my intention.”

Perhaps it was Helnwein’s attempt to pull an Andy Warhol: after all, the New York pop artist had already famously painted two of the Fakehawks gang, Presley and Monroe.[8] This theory is supported by the fact that Helnwein met Warhol the year before he created Boulevard, in an encounter that sounds akin to a religious experience:

Andy invited me to the Factory in New York [in] 1983 and after he told me how he loved my work, he asked me to follow him into an empty room where we sat down opposite to each other and he just froze and he didn’t say anything and he didn’t move. We sat there in silence for some time and I didn’t know what to do—at first it was strange and it felt kind of awkward, but then slowly everything started to transcend and the tension dissipated and nothing seemed important anymore. Andy looked like a wax-dummy in the posture of a pharaoh that had been dead since thousands of years—the room around us became darker and darker and the white of Andy’s face and hair got a glow so intense that it started to burn my eyes. I realized that we were floating now somewhere in outer space and nothing mattered anymore and I raised my Nikon and shot.

Lou Reed later told Helnwein, “Your picture of Andy is the only one I have seen that shows his true self.”

The instinct to alter a famous painting and call it a new piece of art is not without precedent. For his 1919 “readymade,” L.H.O.O.Q. or La Joconde, Marcel Duchamp painted a moustache on da Vinci’s Mona Lisa and added his signature. In 1964, Walt Disney animator Ward Kimball published Art Afterpieces, in which he added contemporary details to famous paintings for laughs, like placing a gigantic cheeseburger in the lap of Portrait of a Young Woman in White (c. 1798). Nevertheless, Helnwein’s popular painting seems to function as a kind of ground zero for contemporary visual mash-ups. It presages so much of what we now see on social media daily, accomplished by anyone with basic Photoshop skills—think of the image of Bernie Sanders wearing mittens placed in every setting imaginable, post–Biden inauguration.

With this in mind, it might be surprising to learn that Gottfried Helnwein is not the artist who continually recombined these four celebrities into the nostalgic scenarios on the walls of so many American diners. That’s someone else. They’ve never met, it turns out—but they do share a publisher.

Helnwein had no interest in taking an artistic cue from Boulevard’s success, combining pop culture with high art in easily sellable ways. You can tell this by glancing at his subsequent output, which has grown only darker and more disturbing over the years. R. Crumb, of all people, once called him “one sick motherfucker,” and later collaborators would include Marilyn Manson and the band Rammstein. But Boulevard was a bona fide poster best seller, so not creating more work like it was akin to setting a pile of money on fire.

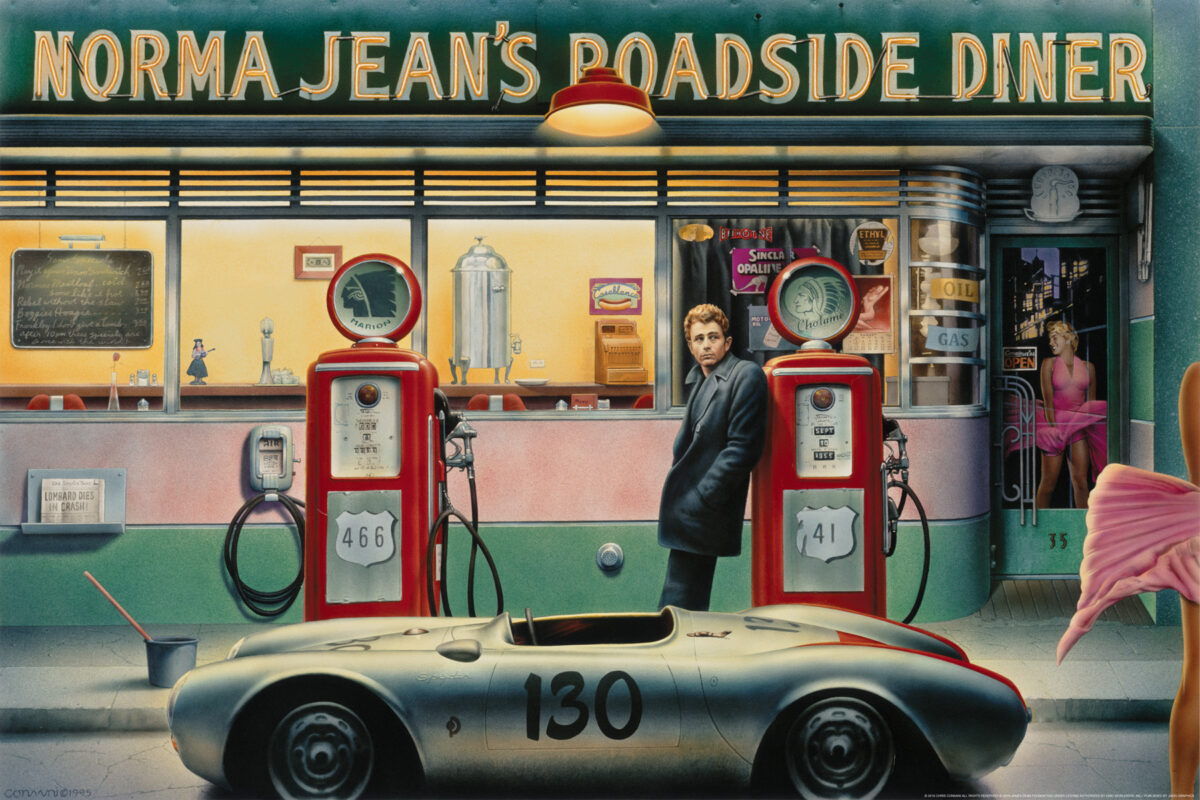

“The way I got into doing these posters,” Chris Consani tells me over the phone from Manhattan Beach, California, “is that Helnwein didn’t want to do it anymore, because he wanted to be a serious fine artist. And what an amazing artist that guy is.”

Consani was born in Washington, DC,[9] the son of a Secret Service agent and a painter. “The house could be burning down and she’d still be painting because she was so intense,” he explained of his mother’s artistic devotion. Watching her, fascinated, Consani soon developed his own interest in painting. He attended the University of Southern California and the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, going on to create memorable commercial work, like the poster art for National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation and Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker. Well into his professional art career, Consani met Dennis Gaskin, the publisher of Helnwein’s Boulevard image, and offered to pick up where he left off.

“You know those Highlights kids’ magazines in the dentist’s office?” Consani asks. “They had these black-and-white pictures with hidden images in them. I always thought that anyone who was a hard-core black-and-white movie buff, like me, might be able to spot a lot of hidden trivia in my paintings. So there’s little references to all of their movies and lives in the paintings.” The visual-puzzle concept was paired with the idea that the tragic spirit of Helnwein’s Boulevard could be ditched for a more playful mood, where all four figures are interacting with one another in some way. Consani pitched this concept to Gaskin, who agreed to try it out, and thus his Hidden Truths series was born.

From the start, Consani tried to make the paintings different from Helnwein’s original. He initially substituted Clark Gable for Humphrey Bogart, but fate intervened when they couldn’t get permission for Gable’s image. (Gaskin was one of the rare producers of these kind of posters, Consani explains, who actually paid royalties to the estates of the dead celebrities.) In this way, the Fakehawks Four were preserved as a unit, and Consani set out to develop a fresh dynamic. “I wanted an emotional interplay between Dean, Elvis, and Marilyn, and almost to insinuate that [the two men are] vying for her [at the same time],” Consani says. He agrees with my assessment that Bogart is the perpetual odd man out, but stops short of cosigning my interpretation that he’s trapped in some kind of cursed existence as a permanent witness to others’ lives yet never living his own.

Consani isn’t the only artist who paints scenes with the Fakehawks Four, but he is the most prolific and best-selling. (“I’ve seen a lot of the other ones that have been done,” he says, “and I didn’t like them, because it doesn’t look like they’re relating to each other.”[10]) Even as he critiques his competitors, Consani remains humble about his success. Reviewing his paintings with me, he can only see things he wishes he could change. We look at Royal Flush, in which the Fakehawks are seated at a blackjack table. Bogart deals, Dean has just won big, Presley is shocked at the loss, and Monroe eyes Dean as if he may now finally be worth her time. Consani is right about its flaws: this one does look like a janky collage onto which he has forced facial expressions from old photos to fit a story. The other paintings have a more effortless, realistic feeling to them.

I admit I sometimes find it oddly comforting to look at these four icons living on together in a painted midcentury eternity—where James Dean is tending bar for the other three and Humphrey Bogart can’t be bothered to look up from his newspaper—even as another part of me winces at how deeply cheesy they are. But the paintings are also a stubborn reminder of a fading monoculture in which there was nothing unusual about selecting a group of four white people meant to represent the best of what Hollywood had to offer. Even with their high-art origin story, these paintings are examples of nostalgic, accessible pop cultural imagery; none of them would ever appear in a serious exhibition in America.

Still, there’s an argument to be made that these posters are viewed and enjoyed by far more people than most pieces that sit in museums. While a brilliant canvas can challenge the viewer to determine the intent and meaning behind it, Consani’s Hidden Truths paintings tell you exactly what they’re about the moment you see them. If you then want to be challenged, don’t worry: he has stocked these images with Easter eggs meant to reward attentive observers. It’s the perfect kind of thing to toy with while sitting in a diner, trying to decode all of the posters’ secrets with a friend, or alone—like an activity placemat for adults.

Consani completed thirteen Hidden Truths posters before calling it quits. He and Gaskin felt they had saturated the market with the concept, though he notes that sales and licensing of the images continue, even if their popularity is nowhere close to its height in the ’90s and aughts. Consani and his friends encounter the images out in the world all the time. I do too. As I stare at one painting framed and hanging in the ’50s Diner in Dedham, Massachusetts, I wonder if their unchallenging, comforting tone betrays Hopper’s original Nighthawks in a meaningful way, and whether or not that matters. Then I have a realization: If someone were to paint this diner scene right now, with myself and three other people, all sitting alone at the counter just after dawn with coffee and the paper, they would surely include the detail of a Consani painting hanging on the wall. In other words, a modern-day Nighthawks might contain a Hidden Truths painting within the painting. There is something absolutely uncanny about Consani’s images looping their way back toward their original, twice-removed inspiration, and how they now reside almost exclusively in the original setting of Hopper’s masterpiece: a diner.

*

[1] It was known as the Chase School at the time. There, one of Hopper’s teachers, Robert Henri, would publish a 1923 book titled The Art Spirit, which would go on to become a kind of bible for film director and painter David Lynch. Hopper’s influence on Lynch’s work, on both the screen and canvas, is often vividly clear and at times seemingly presented in overt visual homages.

[2] Hopper loved the cinema; if he wasn’t painting, he was reading or at the movies, and soon cinema would love him back.

[3] This was not a coincidence. Jo, a painter herself, became both Hopper’s manager and his only model, and she excelled in both roles. Their relationship was complex, to say the least, and often deeply fraught, Jo serving simultaneously as his muse and foil. “Someday I’m going to write the real story of Edward Hopper. No one else can do it,” she wrote in a journal. “You’ll never get the whole story. It’s pure Dostoevsky. Oh, the shattering bitterness!” There is a plainly valid interpretation of the fact that her rising career was derailed, or willfully sacrificed, in service of Hopper’s.

[4] An enormous amount of amateur detective work has gone into ascertaining the precise location of Hopper’s inspiration. Bob Egan of PopSpotsNYC.com places it at 70 Greenwich Avenue, but he also notes that this inspiration goes well beyond a building. Hopper biographer Gail Levin writes that he loved a 1927 Hemingway story titled “The Killers” so much that he wrote to the editor of the magazine that published it—Scribner’s—to express his admiration. The story opens with a scene not unlike the one depicted in Nighthawks. Furthermore, the story was accompanied by a line drawing by C. LeRoy Baldridge depicting two men wearing fedoras, interacting with a male diner employee; examining it, one feels as if they’re potentially looking at an early Hopper sketch exploring the concept of these type of men inhabiting a locale like the one also seen in Nighthawks.

[5] Of his introverted, stoic nature, Jo Hopper once remarked of her husband, “Sometimes talking with Eddie is just like dropping a stone in a well except that it doesn’t thump when it hits bottom.” The artist disliked explaining where the lonely feelings expressed in his paintings originated, only offering some version of “the whole answer is there on the canvas.” Hopper’s biographer Gail Levin highlighted how his unusual tallness naturally separated him from everyone else, and Jo even went so far as to suggest that his lonely portraits of lighthouses were meant to represent that isolation. The models for the Nighthawks couple who seem so distant yet so intertwined? Jo and Edward Hopper.

[6] The original source of the painting’s title is the 1933 Al Dubin and Harry Warren song “Boulevard of Broken Dreams,” which itself has a serpentine history of influence. Originally released by Dubuque, Iowa’s, Brunswick Records, it appeared the following year in the 1934 film Moulin Rouge, which has no relation to subsequent films of the same name. (The song was later used as the A side of Tony Bennett’s major-label debut 45 with Columbia Records in 1950.) After Helnwein’s repurposing, it became the title of a biography of James Dean in 1994; Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong explained that he “nicked” the title of the band’s 2004 song from Helnwein’s individual portrait of Dean by the same title, which the artist created in conjunction with the painting of the foursome. One of the most popular uploads of the song—116,695 views, 883 likes, 78 comments—is set to a montage of Hopper paintings, though no commenter has pointed out that the song is related to Nighthawks and Hopper only by way of parody. It’s as if Helnwein’s Boulevard’s influence has equaled that of the original, which is a tremendous, unlikely accomplishment in itself.

You can keep boring down into this vein. Jochen Markhorst’s book entirely about Bob Dylan’s 1965 song “Desolation Row” makes a convincing case that the chain of influence for pairing loneliness or despair with specific locales in pop music titles went something like this: “Boulevard of Broken Dreams” (1933) to Hank Williams’s “Lost Highway” (1945) to “Heartbreak Hotel” (1956) to “Highway of Regret” (1959) and then to Dylan’s “Desolation Row.” This is worth noting only because Dylan’s own painting style has so often been compared to the aesthetics of Edward Hopper, and recently, the singer’s 2020 painting Night Time in St. Louis was identified as a clear homage to Nighthawks, with the Telegraph remarking that “it’s as though Dylan has taken the realism of Edward Hopper for a big night out on Desolation Row and left it reeking of nicotine, gasoline and regret.” Furthermore, Helnwein’s Boulevard of Broken Dreams is not unlike the concept of Dylan’s “Desolation Row” expressed visually, complete with famous figures standing in for the lonely lives and actions of regular folks (he had to “give them all another name,” you see).

[7] You could make the case that Helnwein is playing with Hopper’s symbiotic relationship with American cinema—both drawing inspiration from it and directly influencing it—by having some of its biggest names literally invade one of his paintings, but this really does not seem to have been his intent, nor is it a popular interpretation of the work.

[8] Warhol had infamously painted Presley and Monroe in the early 1960s, but in 1985, a few years after the arrival of Helnwein’s painting, Warhol produced a portrait of James Dean too. Only Bogart, forever the odd man out, never received the Warhol treatment.

[9] The fact that the few online biographies of Consani claim he’s Canadian is a great example of his indifference to his internet presence. Consani was already doing well, he figured, and he thought, “Why upset the apple cart? I know I was born in DC.”

[10] Google “Evening at Rick’s by George Bungarda” for a good example of a clumsy attempt at the Consani concept. Bungarda also has a 1993 work titled Legends Theatre, in which Jimi Hendrix, Buddy Holly, Elvis Presley, and Jim Morrison are all performing together onstage (that’s a lot of singers), while Bob Marley, Janis Joplin, and even Beethoven(!) are reduced to audience members.