If you drive far enough south in Douglas, Arizona, you eventually hit the wall. You’ll pass through tidy avenues lined with new ranch homes and the stately old brick houses built for mining officials back when Douglas was a company town, when there were jobs here besides those offered by the Border Patrol, Wal-Mart, and the prison up the road. But this is the Sonoran desert, despite the lawns, and minitornadoes of red dust keep whipping themselves up in the streets and just as quickly dissolving. Then the avenues give way to a long, straight unpaved road, then a drainage ditch, and then the wall.

Constructed of adjoining rectangles of corrugated steel built to serve as landing strips for American planes in Vietnam, the wall climbs at least ten feet high for miles to the east and west, a rust-colored scar on the surface of the desert. When it passes through a wash, the landing mats are replaced by tall rectangular steel girders filled with cement, spaced just widely enough that water can pass between them, but not human limbs. Through those spaces, you can see into Mexico—more red dirt and skinny ocotillos, a thirsty-looking cow, a makeshift grave of piled stones and plastic orange flowers, the same blue sky.

If you linger here for more than a moment, the lenses on the Border Patrol camera towers will spot you, or you’ll trip a magnetic sensor or a seismic one, and one of the nearly 10,000 Border Patrol agents stationed along the 2,000-mile southern boundary will roll up behind you in a Jeep, lights flashing. If you are allowed to drive on, big-eared desert hares will leap in front of your tires, and more dust devils will rise and twirl to the right and to the left. Then the wall will block your view again until, without warning, about five miles east of town, it comes to an abrupt end, and nothing but a few sad strands of torn barbed wire remain to bisect the enormity of the desert.

It’s hard not to laugh out loud: all this mad fuss over so much nothingness. What are we so afraid of?

*

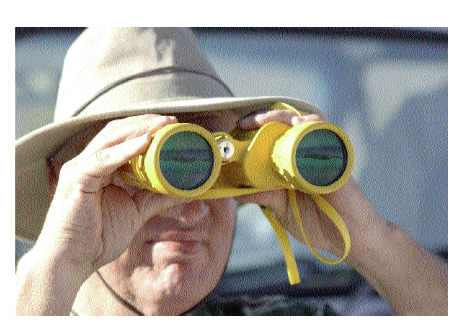

Jim Gilchrist’s home is a good nine-hour drive from the barren stretch of Arizona desert about which he has become so insistently concerned. Despite this distance, Gilchrist has for months now been planning to erect a human fence along the imaginary line separating the United States from Mexico, to station volunteers armed with binoculars, radios, and often pistols at quarter-mile intervals in an effort to protect what they and Gilchrist understand to be America from all that it is not. Gilchrist is a retired CPA, and lives with his...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in