THE ACCEPTANCE OF PERSONA

Every artist expresses persona. For performers, the public face is inside the art. The work of Charlie Chaplin, Billie Holiday, Ana Mendieta, or Jimi Hendrix cannot be separated from the undeniable power of persona.

For artists who send their work into the world, persona may be less apparent. Writers, painters, and composers will have little relationship to an exterior self unless they actively choose to engage it. Such private-minded artists may find the very subject of persona to be taboo, distasteful, and cringeworthy. They might bristle and scoff at the possibility that they, too, have constructed and worn masks for many years.

In such cases, persona becomes a hideous relative, ignored, avoided, or acknowledged only when absolutely necessary, in a huff of obligation. Negligence may lead someone to believe that persona has been extinguished, but it has not.

If an artist releases art into the world, they have already created immortal persona. When we expose ourselves and ask for the world’s attention, we give birth to strange new forms of self, shadowy doppelgängers who will live on even after our death.

Punk, hip-hop, Fluxus, surrealism, goth, transcendentalism, the Beats—many of the most potent artistic movements are defined as much by the artists as by the work itself. Any exhibition of art is also an exhibition of its creator. Denial is futile.

I was once a persona hater—which, at times, could be a form of persona in itself. To me, dealing in public facades was, in the best cases, an irritating distraction. In the worst cases, it was an inauthentic scheme, at direct odds with the mission of artists: to seek and present truth.

To define some terms: persona is constructed, while personality tends to be a more passive phenomenon, shaped by genetics and the vicissitudes of life. Persona is an invented, enhanced, and performed version of personality, which, I came to understand, makes it a natural material for artists, for whom invention, enhancement, and performance are the primary means of working. Why would a creative person not be a creative person?

The term persona was coined by Carl Jung as “a complicated system of relations between individual consciousness and society.” Jung says the mask is essential to human interaction, and without it, we suffer. But we can also find trouble if we overly identify with it. For Jung, integration is the only path forward.

In the century since Jung invented the concept, the word has developed a stench of pettiness, as if persona were only for the swindlers and fakes. It is often associated with the kind of superficial traits that rarely support meaningful human exchange: seductive charisma, affected coolness, self-absorbed confidence. These qualities look best from afar, on camera, or through the rose-colored lens of history. Up close, they refuse intimacy.

I am bored by the contemporary persona archetypes: the narcissist, the scenester, the “on brand” celebrity, the campaigning politician—all of whom are trying to transform themselves into perfect icons. Encounters with such forms of persona are often repulsive. Like a wax figure, they stand still, uncanny, dead.

Artistic persona, the subject of this text, encourages the contradictions of our changing selves. Instead of a fixed image, consider persona as a field of infinite expression, as unresolved and irreducible as human perception—“a complicated system,” as Jung says. For this reason, I avoid the traditional grammatical usage of a persona, and consider it as a fluid substance, forming and re-forming to the manipulations of the artist.

Artistic persona does not require self-obsession, only an acceptance of the true nature of artistic exchange, in which evidence of the self is always present, even if hidden or ignored. The line between self-expression and selfishness is razor thin, but persona, when worked thoughtfully, is a tool for profound connection. Bob Marley’s physical energy amplified his music. Gertrude Stein was an extraordinary writer but is still best known for the effects of her magnetic social presence in 1920s Paris. Like a sonata or a painting, the presentation of self can be a window into consciousness and a generous display of vulnerability.

For me, communication is the fundamental pleasure of art. While I enjoy fetishizing a sculpture for its sensual thingness, I ultimately want to feel a relationship to the vitality that produced the object. This is true even in my relationship to the natural world: a mountain stirs up awe not just because of its material presence, but because of the universal forces that lifted it into being.

THE TRANSMISSION OF PERSONA

Persona is artificial, which is to say, it’s created by humans. So is paint. So is a piano. So is a seventy-thousand-year-old arrowhead. This does not corrupt persona or make it inauthentic, whatever that word means. The word art has the same root as artificial. One of art’s few defining characteristics is that it is made, in part, by people—not by a deity or wilderness or chaos. (Animals and plants, as aesthetically expressive as they are, do not make what we usually call art.)

Still, there is a feeling, especially among artists, that a successful sculpture is like a tree in the wild—unspoiled by human effort. It’s a hope that our art contains a higher truth than we do. For many people, this might even be the purpose of art: to transcend the messy human being and present a clarified natural harmony.

“I wish the art I make to have nothing to do with me,” the artist Seth Price writes. “The goal is to capture something beyond the human.”

Mystics call this channeling. For the mystic, the artist is not the creator but a medium through which creativity flows. Human personality is bypassed and a divine power is responsible for the art. Some arrive at this idea misanthropically, through a disgust at humanity, while others see this process as a visitation from the genius, or genie. The writer Ottessa Moshfegh once described channeling to me as hearing a radio wave in her mind. The musician Pat Metheny explained improvisation to me in nearly the exact same words.

This is a common experience among artists, and yet it’s reasonable to think that this energetic transmission, even if divine, is shaped by the person through which it travels, just as a radio signal vibrates distinctly in different speaker cones. The artist may not be the total creator, but they are certainly a collaborator, leaving some trace of their earthly presence. You might call this trace a personal style.

Moshfegh and Metheny, for example, both have distinct artistic styles, despite their process of channeling. They both have spent their lives studying the techniques of their craft and would certainly take credit for the distinctive quality of their novels and music. Likewise, each artist expresses persona, dressing, speaking, and opining in ways that are as idiosyncratic as their art. In this way, channeling need not exclude persona. Inward and outward exploration lead to the same place. God, as the mystics say, is already inside us.

Persona is a transcendental phenomenon and it, too, can move through us as selflessly as the transmission of art. It eludes scientific measurements. Like art, it shows itself through matter (e.g., speech, fashion, gait, countenance, behavior) but is an expression of deep feeling. It is a counterpart to genetics, a conscious way of freeing ourselves from the flesh through imagination. Persona can even exist online, or in art alone, without any physical body to support it. Unlike the soul (permanent, impenetrable), persona is not who we are, but what we create.

THE COLLABORATION OF PERSONA

Build a good name.

—William Burroughs’s advice to a young Patti Smith

The alternative to persona would be a constant public exposure of our most intimate parts at all times. Is our soul on display everywhere we go? Should it be?

For artists who value privacy, persona may, in fact, allow for further protection of the self. Richard Tuttle said to me, “The only way I could survive growing up was to construct a persona.”

The artist Mika Rottenberg once told me, “All artists are control freaks.” The manipulation of self is often one of the few things in life we can reliably control, and still, the subconscious will always interfere.

Vladimir Nabokov required that all interviews with him be conducted in written correspondence, so that he could edit every word before publication. Eventually, he collected them in the book Strong Opinions, as his own document of persona, and whether he intended it or not, he had created a portrait of the author as a perfectionist.

Neither art nor persona can be entirely controlled by the artist. Once art is unleashed into society, it becomes a dialogue, and the audience becomes a collaborator. This is apt, because art and persona both come from a desire to connect with another life, and they will always be shaped by misinterpretation. They will never be understood as the artist intended.

In “The Death of the Author,” the literary critic Roland Barthes argues that readers should utterly ignore the opinions of the artist when reading a text. Similarly, the philosopher Martin Heidegger believed that the only information we need to know about a philosopher are the dates of their birth and death. He was clearly anti-persona, which makes sense for the author of Being and Time, a book that tries to describe broad, abstract laws of reality, rather than reveal any facts about the author.

But Heidegger was a Nazi, and the people who are aware of his fascism likely outnumber those who have read his vast and daunting tome. So is it possible to approach this book without an awareness of his personal life, however impersonal the words might be?

For years, I believed in such intellectual possibilities. I told myself a fable of pure art. It’s a scenario that many artists imagine: when art enters the world, it is experienced in a state of isolation, without undesirable context or awareness of the artist’s life. In this idealized situation, the audience is ignorant of all things the artist feels do not serve the art, but knowledgeable about everything that does.

This desire for total control eventually leads to something like the white-cube gallery, a place that attempts to present art as if it were floating in space, disconnected from culture, observed with pristine amnesia. Pure artifice.

I could scrub my presence from this essay, remove this first-person perspective, and speak from an omniscient, ambient voice. Instead, this essay contains some part of me, presented in a bundle of sentences, edited with care. This is how the assembly of persona slips into our lives—not as some grand strategic plan, but in the gradual development of an artistic vocabulary: I would never wear that outfit, or play that instrument, or behave like her, or use that word to end this locution.

The boundaries of our persona are defined through an accumulation of choices. If I hid my presence, as another writer might, the authorship would still be here, in my tone, in the movement of my thoughts, and even in what I refuse to reveal.

THE BALANCE OF PERSONA

One thing is needful.—To “give style” to one’s character—a great and rare art! It is practiced by those who survey all the strengths and weaknesses of their nature and then fit them into an artistic plan until every one of them appears as art.

—Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science

I became an artist to make art, but also to be an artist. I wanted the open schedule, the liberated social role, the romantic tropes. Mostly, I wanted to be connected to a long line of humans I admired, most of whom I’d never met and had experienced only as inspiring forms of persona. John Coltrane, Andy Kaufman, Virginia Woolf—these humans were artistic beings. They were ideal containers for their art, and I loved them for it.

The artists I loved were not all good people, in moral terms, but they were good figures, in aesthetic terms. In the documentary Cy Dear, the artist Giosetta Fioroni describes her friend the fellow artist Cy Twombly in a seemingly critical way, as “interested in only himself, meaning his person, his own emotions, his own travels, his own movements,” only to conclude by saying, “He was truly a masterpiece.”

Through these artists and others, I learned that the human, the art, and the lived life all form a kind of complete statement. I have since thought of these elements as the subject, object, and verb. Together they form a full sentence of an artist’s expression. The viewer, too, experiences the art (object) in relationship to persona (subject) and to how the artist lives (verb), which inevitably influence how the art is made. Reconciling this trinity and keeping it in balance becomes a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art.

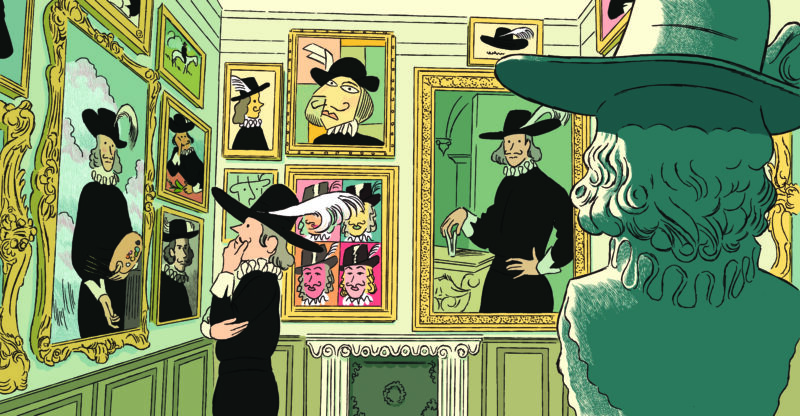

Picasso said, “It’s not what an artist does that counts, but what he is,” which is why he spent his energy creating both his pictures and his legend. He exhibited his paintings and life in tandem, in galleries and in cafés. Now when I look at a painting by Picasso, I see Picasso, the man (striped shirt, confident smirk, macho bravado) alongside the story of his life (war, bulls, affairs). It all happens in one look. My mind and eye merge.

For any artist who achieves success, this is inevitable. Kahlo, Dalí, Kusama, Warhol. It’s nearly impossible to view these artists’ works and not think about the way they acted, lived, and thought. Rene Ricard, describing Basquiat in New York, wrote that “one must become the iconic representation of oneself in this town.”

The conflation of subject-object-verb is equally true of composers and writers. Think of Hemingway, Stein, Baldwin, Beethoven. If one looks back to the history of art, this kind of public trinity might have seemed escapable—it wasn’t—but now, in the age of the internet, it’s undeniable that the artist, art, and life are ineluctably wired together. Celebrity is now a spectrum, not a binary.

The philosopher Boris Groys considers this an era of narcissism, a term he defines as “understanding one’s own body as an object, as a thing in the world—similar to every other thing.” He writes this in his book Becoming an Artwork, whose title is another way of saying the same thing.

THE NEED OF PERSONA

I have never loved a work of art because I consider it only a residue. What attracts me is the thought of the artist… The work is a deposit from which the artist has already detached himself.

—Lucrezia De Domizio Durini on Joseph Beuys

In our current moment, people are often more fascinated by persona and the artist’s life than they are by the art. This can be a lopsided experience.

An artist’s personal activities—social media, politics, sexual peccadilloes—increasingly dictate whether their art is appreciated or ignored. What we narrowly call an artist’s identity (race, nationality, gender) drives many of the most important critical perspectives toward art, sometimes utterly defining its interpretation.

Artists who actively fold their identity into their work may enjoy subject-verb interpretations. Others may not want their art affected by their private lives, or attributes they inherited at birth. Instead, they might prefer to brew up a new identity, something as eccentric and full of possibility as their own body of work.

I, too, am sometimes compelled more by the artist than by the art. A bold interview with an artist can show me how to see a picture. A writer’s creatively lived life can inspire me more than the same person’s impenetrable new novel. Hearing the poet Anne Carson speak about literature makes me love her work even more. In this way, a well-balanced persona acts in service of the art. But ultimately, the full art experience feels complete only when subject, verb, and object all hum with vitality.

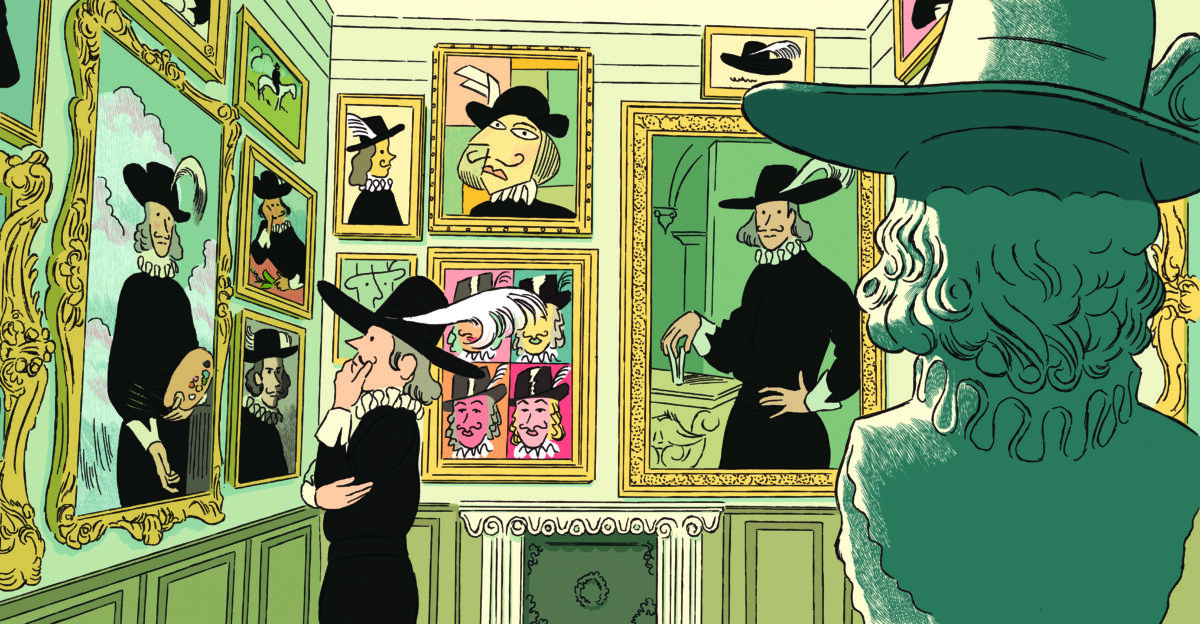

The artist Jordan Wolfson is well known for his persona, which is, like his sculptures and videos, alternately vulnerable and pugnacious. He admires the way pop musicians navigate persona as part of their work, and how their audiences are willing to conjoin artist with art. He considers David Bowie a master of the malleable self, able to continually bend his appearance and behavior to his changing music.

“People develop persona over time,” Wolfson said to me. “We all have the seed of it. And if you feed it—as, say, Jeff Koons did with his Made in Heaven series—it can grow.”

The artist and writer David Salle often analyzes persona in his criticism. He describes the paintings of Philip Guston and Marsden Hartley by referencing their “fully fleshed, meaty” bodies, pointing to the physical aspects of persona. He regards the success of sculptor Urs Fischer as largely due to “the force of his personal charisma.” (Conversely, the critic Benjamin Buchloh dismissed the work of Joseph Beuys for being too dependent upon charisma.) Salle isn’t ignoring the art by writing this way. He understands that each picture is, in part, a self-portrait. All art reflects the artist just as every character in a dream is the dreamer in disguise.

THE PROBLEM OF PERSONA

I look inside and my model is really myself.

—Louise Bourgeois

Recently, a queue wrapped around the block for the opening of Basquiat’s exhibition Made on Market Street at Gagosian Beverly Hills. A month later, another line formed at Jamian Juliano-Villani’s show It at the gallery’s New York location. Do people love this art so much? People certainly appreciate it, but I believe persona brought the crowds.

For years, Juliano-Villani has actively nurtured her image alongside her paintings. She live streams while eating a midnight spaghetti dinner. She talks to online followers while trying on new outfits and opining about the art world. She includes herself in her art as a character, transforming her presence into a literal icon. During one of her many interviews, she said she’d been “cosplaying for 10 years… This is the cartoon version of me… It’s like all up here.” [Points to head]

Juliano-Villani cultivates big art-star persona, but even the little-known artist must deal with the presentation of self. The invention of persona begins the moment an audience encounters a new artist. Even with no other stimulus, the art and its context (when, where, et cetera) can conjure an image of the author. Again: once attention is paid, persona is there.

Only through unintentional obscurity can exhibiting artists avoid persona. Few artists desire this now, but in the past, anonymity was often a required condition of making art. Before the rise of individualism in the Renaissance, artists did not sign their work, and music was anonymously composed. Ancient forms of art, such as Egyptian or Aztec, were made by groups of writers or artists, and might not exhibit enough traces of a single hand to hold singular persona. This art aimed to capture the expression of a community, not of a person. Contemporary viewers may find it difficult to imagine persona behind the painted beasts in Lascaux, but someone was in that cave and they were trying to communicate.

Intentional obscurity, on the other hand, is a common method of avoiding persona—refusing social media, or press, or published photos—but this usually backfires, turning the artist into a mythical hermit. Martin Herbert’s book Tell Them I Said No is a document of this phenomenon, chronicling the efforts of Lee Lozano, Cady Noland, David Hammons, and other visual artists who actively erase evidence of themselves from the world. In all these cases, refusal draws attention to the thing refused. Secret identities stimulate fascination from viewers, and the artist’s absence becomes primary to the art. The effort of erasing persona is additive, not subtractive.

Every Trisha Donnelly sculpture I’ve seen is, in some way, an artifact of her retreat from the media. Every lover of J. D. Salinger knows of his grumpy, reclusive ways, and several years ago, an entire documentary film was made about the many attempts to track down the author’s whereabouts.

Perhaps the most effective method for backgrounding identity is not a dramatic physical exodus, but a public dulling of the self. This kind of neutrality is how many artists respond to the problem of persona, but this, too, can harm the work. Ambivalence is a generally unattractive quality in a person, and a boring presence can drape over art like a wet blanket, dragging against the work’s own energetic momentum.

Other artists may distance themselves from persona out of fear that they might begin to identify with such outwardness. This may be a noble effort, but fear, too, can disturb the art.

Attempts at flatness also won’t matter if artists achieve fame. Of the artist Jasper Johns, the photographer Hans Namuth once said, “Jasper doesn’t pose,” which is to say that Johns doesn’t act like a man with persona. But this anti-posture has not hindered public interest in his life. In fact, this very quote is taken from Michael Crichton’s biography on Johns, a testament to the infatuation Johns has inspired in one of his close friends.

THE POSSIBILITIES OF PERSONA

I am trying to get to that place where nothing matters except the flow of this persona.

—Ebecho Muslimova on Fatebe, the alter ego in her work

Persona is not an obligation. The artist has the right to fully ignore their social identity, but this does not mean persona can be erased for the beholder. Instead, it can be warped, accented, refined, or faded like any other material, and each artist can develop their own technique for transforming it.

Some artists may use their presence to confuse. Cindy Sherman displays a crowd of varying personae in her photographs, which ultimately destroys any idea of a real Cindy Sherman. The artist Hanne Darboven wrote her personal correspondence with an intention to publish it, and according to writer Alex Bacon, she used these letters to invent her biography as a character within her oeuvre, harnessing the medium of private revelations to create public persona.

For many artists, the altered self is neither additional nor ornamental, but necessary. Like the Kabuki mask, persona allows someone to step outside their ordinary consciousness to make something beyond their abilities. A mask may help an artist to maintain distance from the intensity of the process, or to access something their personality cannot knowingly express. Such transformations can occur privately in the studio, explicitly in public, or even unconsciously.

The artist Nora Berman uses the digital avatar “Sparkly 22 Miracles” for her seven-hour-long, endurance-length online performances. The artist Madam X employs her pseudonym for mystical purposes, feeling that this name points to the true appellation of the maker, a parallel spiritual being.

False identity can relieve the artist of culpability. Graffiti writers assume monikers. Political activists wear disguises. The Guerrilla Girls dressed like gorillas to avoid arrest. The Brontë sisters and George Sand used male names to avoid misogyny. Stage names are common for pop musicians who command audiences larger than their birth-name personalities can handle.

Filmmaker Lynn Hershman Leeson wore the name Roberta Breitmore for five years, until she exorcised that persona in a ritual. Duchamp used R. Mutt and Rrose Sélavy to refuse his past. The artist Lutz Bacher never revealed her real name. Nor has the writer Elena Ferrante.

Some artists tell lies to create confusion around their personal lives, offering conflicting biographical information. For years, the trickster-artist Maurizio Cattelan sent the curator Massimiliano Gioni to be interviewed as a fake Cattelan. The artist Terence Koh often provides differing birth information to keep his past a mystery.

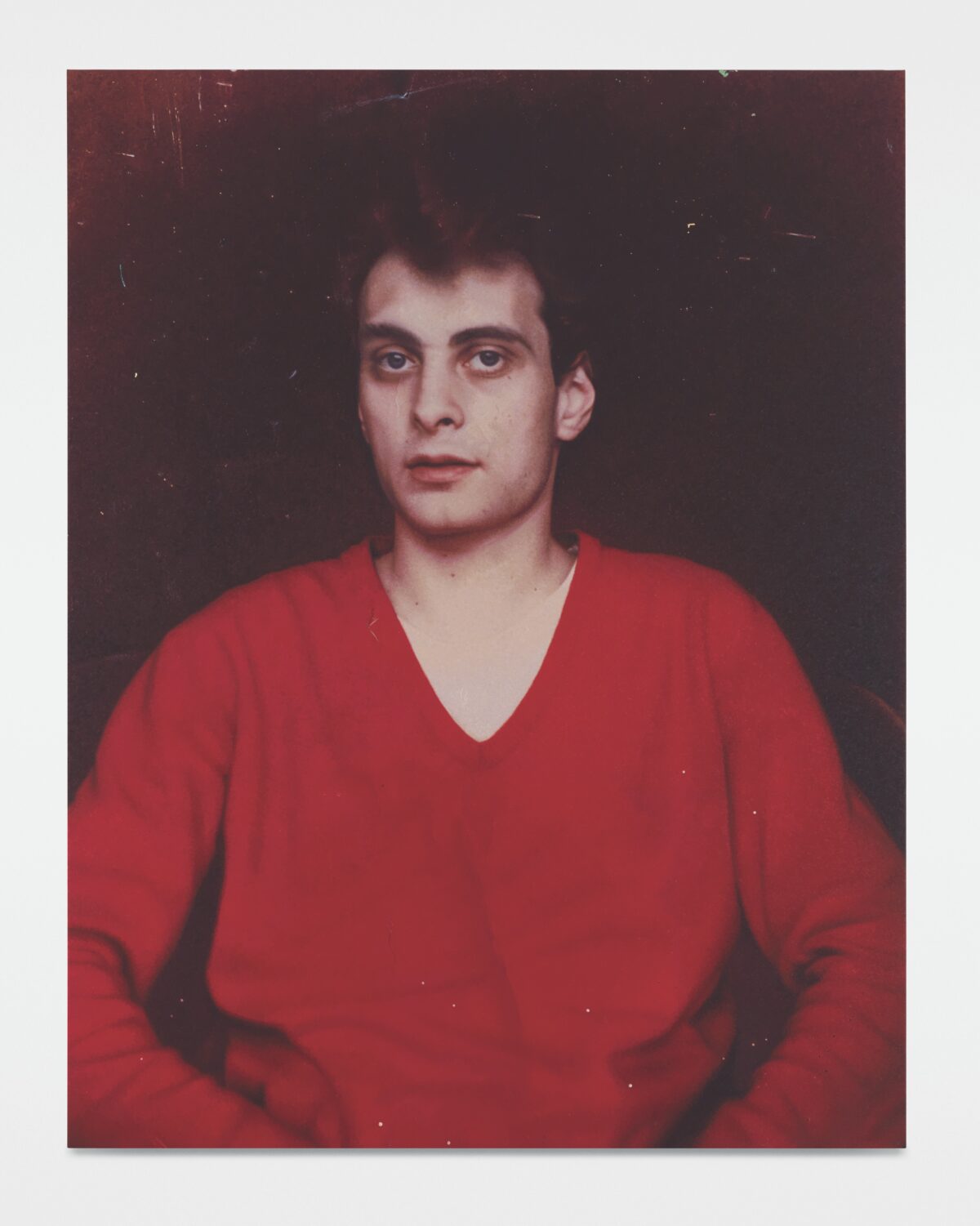

Clowning is a way for performers to expose and hide themselves in plain sight. The artist Pope.L spent an entire career placing himself in shameful situations—balancing a pie on his flaccid penis, shitting onstage, and crawling through New York City gutters. It’s almost impossible to critique a persona mired in so much embarrassment.

Albert Oehlen wrote an autobiographical film, The Painter (2023), in which an actor portrays Oehlen as a fool, struggling to paint, snapping at interviewers, and prancing through his own exhibitions with arrogant delight. When I watched it, I knew it wasn’t Oehlen onscreen, but now I can’t help but think of the film’s pompous buffoon when I step into the artist’s exhibitions.

THE FREEDOM OF PERSONA

Persona need not be aesthetically connected to any aspect of the work. Some artists use persona to rub against the art, creating a nice, satisfying dissonance between subject, object, and verb.

Georges Bataille dressed like a gentleman while writing depraved sexual horror. David Hammons is an artist of the streets, scouring them for trash, but he regularly positions his objects in a high-class stratum of society, at the bluest-chip galleries, among the wealthiest collectors.

Agnes Martin, a painter of meditative serenity, who lived in ascetic simplicity, also enjoyed driving her expensive BMW at top speed through the desert. Takashi Murakami, best known for depicting a bright world of smiling flowers, often appears on social media with his face sagging in depression and wet with tears, in a display of his struggle with mental health.

These variations of persona bring new colors to the art, but they are never the whole art. Persona is just one among many materials: oil, marble, video, content, form, self. The real art is always below the surface.

Gertrude Stein called this the “bottom nature” of people, an essence that comes through in art, regardless of the material. The soul can be decorated by masks but it can never be fully covered.

Seth Price wrote a novel called Fuck Seth Price, purposely working in the tradition of autofiction, a genre of literature dedicated to the simultaneous depiction and abstraction of persona. In it, the fictional Price says, “Appearance is a red herring… regardless of the artist’s exterior or persona, it is the inner self that manifests in the work. And you can really feel it emanating.” It’s an idea that’s almost completely at odds with Price’s previously mentioned goal of creating art that has “nothing to do with [him],” but artists have no need for uniformity of thought, and Price knows that contradiction will help to enrich the unsettling disorientation at the heart of his work.

THE INTENSITY OF PERSONA

The word persona suggests extroversion, but the manipulation of the self can be as subtle and intimate as our mundane, daily transformations. Each of our interactions—with a family member, a service worker, or an employer—requires minor shifts of facial expressions, vocal tone, and body language. William James said that we have as many selves as we have social relationships. Jasper Johns said, “I think I am more than one person.”

Another word for these permutations of persona could be attitude. Attitude can be felt anywhere in art, such as in the application of material—Helen Frankenthaler’s easy pours of paint; Rashid Johnson’s frantic scratches into melted black soap.

When I see a Wolfgang Tillmans photograph, hung with a humble binder clip, I feel his persona. When I listen to James Blood Ulmer’s liquid guitar tone, I hear an entire worldview.

The artist can also hide a brushstroke, or perform music with mechanical exactitude, creating something so impeccable that it appears that no human intention was ever present. But this kind of labor inevitably points to the kind of thinking that would focus on such details. Precision and virtuosity are evidence of persona.

THE SUCHNESS OF PERSONA

The various forms of persona are not mutually exclusive. The artist Rudolf Stingel, for example, exudes polyphonous persona, using many approaches at once: rough, abstract smears of paint; refined, photorealistic self-portraits; and an avoidance of the media. His manifestation of persona is both gentle and bold, with elements of absence and presence creating a dynamic, expanding tension.

Recently I stood in front of Stingel’s Untitled (2011) in Los Angeles, a painting loosely slathered in golden streaks. Beside me was a man I’d met a few minutes before, who looked upon the picture and described his impression of Stingel—the artist, not the painting—as a “slicked-back hair, wine-drinking, cigar-smoking, big-bellied real estate mogul… I love that archetype!” He laughed. “Nice and baroque.”

I’m not sure how he arrived at this image of the artist, but it seemed as clear to him as the painting before us. Despite the clear persona in his mind, he professed to have a limited knowledge of Stingel, as do I, since Stingel doesn’t make himself particularly well known. Many New York artists I know don’t even realize that Stingel lives in New York, instead imagining him in some faraway compound. I believe Stingel cultivates this sense, as he only very recently allowed photography in his studio, after several decades in the city. Like this, he grows the legend of the wizard behind the curtain.

“Untitled.” © 2010 by Rudolf Stingel. Oil on canvas. 131 × 102 ¼ in. Courtesy of Gagosian.

Stingel rarely conducts interviews, and in one of the few talks I found online, he was salty and terse, and seemed barely tolerant of the situation. In response to one question, he retorted, “If I was thinking about these things I might as well shoot myself.” However, in another interview, he was cordial and responsive to the interviewer, as if he were a totally different person.

His art, too is mercurial. His most significant work includes both self-portraiture and a series of pieces designed to remove his touch, such as those made by the carvings of viewers. Like this, Stingel’s relationship to persona mirrors his slippery relationship to the category of painting, which, for him, includes carpets, Styrofoam, and floor-to-ceiling installations. In his life, work, and persona, Stingel projects an ongoing, relentless state of becoming.

THE DANCE OF PERSONA

Self-consciousness is the enemy of all art, be it acting, writing, painting, or living itself, which is the greatest art of all.

—Ray Bradbury

Inventive persona is never one thing. It’s not a crass caricature or a dating profile. It’s an ecosystem of impressions, forever in flux. The richest persona never settles into easy description and always slips from our understanding.

Dieter Roth, the polymath, once said, “I experience my person as a nebulous persona,” and indeed, he taught his methods to his children and grandchildren, who carry on Roth’s projects and use his name long after his death, as if his person had always been immaterial. This is the kind of understanding that liberates persona from egoic self-control and allows it to spill beyond our limited selves. Persona is a clumsy partner in our dance with culture, moving with the same organic, ever-changing steps as we do.

Last spring, I attended a talk with the artist Nairy Baghramian, who discussed her own negotiations with the art press. She spoke of the lack of critical discourse in the art world, which has led to her receiving an increasing number of interview requests, and to a resurgence of the belief that the only person who can address questions about an artwork is the author.

“The artist’s persona,” she said, “can work against itself… But it’s not all about me. I would rather talk about other artists. I don’t want to defend my work.”

To address this problem, her talk included a viewing of Richard Serra’s film Hand Lead Fulcrum (1968), which, she explained, was created by Serra to answer questions he had been asked about his own work. The film explains nothing.

The artist’s persona need not be a way to explain art, but a vehicle for expanding it. Like the filmmaker David Lynch, Baghramian prefers to refuse to answer questions about the meaning of the work. Instead, she becomes a foil for her art, a means to building further mystery and complexity. “We should not have to be the work,” she told me. “That’s boring. The persona should be constructed.”

This is how persona can be less like a single work of art than an entire body of work—a constellation of choices spread across time. Life is change, and creative thought is motion. Beyoncé naturally transformed from pop singer to country icon. Donald Glover metamorphosed from nervous, skinny comic to slick, grinning celebrity. Miles Davis invented new genres every few albums, always with a fresh, dazzling wardrobe. We watch as these musicians defy the expectations of their role, whether they are jazz musicians or pop stars.

These expectations are in us all. Art, as free as it can be, still brims with standards. There is no such thing as a blank canvas. Always in the back of our mind is the landscape, the portrait, the still life, and whatever appears on any canvas must resist or submit to those expectations.

This is also true for persona. Even the most self-effacing personality must contend with that old, dusty archetype of the starving, tortured artist. Painters, sculptors, poets: the world looks to these artists as society’s sources of authenticity and truth, which, as the tale goes, is found only in the darkest, harshest depths. The true artist must venture into hell and, through great suffering, bring back gleaming wisdom for the rest of us.

Who is responsible for this story? Is it van Gogh? Sylvia Plath? Kurt Cobain? And should we all have to perform this role until the end of time? Who needs us to? And what do we become when we pry off the mask of the serious artist, mix up a fresh palette of persona, and allow ourselves to just play?