On YouTube, you can find hundreds of clips from the animated G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero. It’s been twenty years since the show premiered, but the gaudy palette and campy characters shimmer on the smallest screen. Collectively, these digital relics from an era when the real U.S. military was busy invading Grenada and Panama have been viewed hundreds of thousands of times.

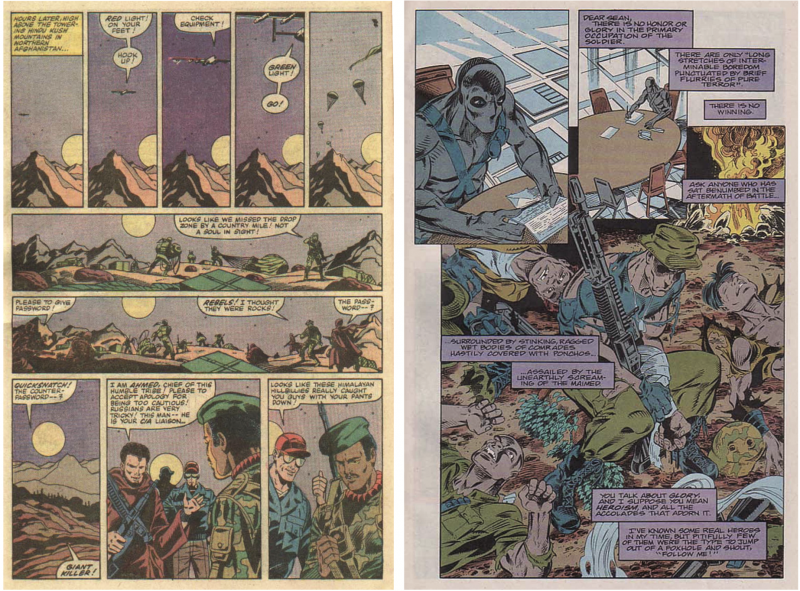

It’s fascinating to view the series’s frenetic opening sequence, in which righteous American commandos battle the evil Cobra army. We meet G.I Joe, as he storms a beach outpost; Flint, wearing his cocked beret; Lady Jaye, throwing spears and clad in sexy olive fatigues; and Shipwreck, dashing into combat dressed like one of the Village People.

Then the Cobra villains emerge, blasting away with laser guns: the mutated snake-man, Serpentor; the leather-clad dominatrix, Baroness; and the mustachioed quack, Dr. Mindbender. Airplanes, boats, tanks, hang gliders, hovercrafts, jeeps, and a supersweet aircraft carrier zoom through the fray. Every image is paired with a shiny Hasbro toy in the Christmas catalog.

G.I. Joe was one of the pioneering “program-length commercials.” By creating an entire television series around a product, these shows dodged FCC regulations that limited children’s advertising. Animated characters helped sell everything from gummi bear candies to He-Man dolls, but G.I. Joe drew more criticism for encouraging both consumerism and militarism.

In 1982, Hasbro’s initial $4 million advertising push for G.I. Joe was the most money the company had ever spent on a single line, spawning a virtual military-toy-industrial complex. Around that time, critic William Crawford Woods wrote a blistering Harper’s essay about G.I. Joe, in which he investigated how the toy company “aimed to reach 95 percent of all American boys aged five to eight more than fifty times each.”

Perhaps Dr. Mindbender embodied Hasbro’s remorse for messing with kids’ brains. He wore a bushy robber-baron mustache, a monocle, a cape to accent his naked muscles, and, most strikingly, an armored crotch-plate. In one issue of the G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero comic book, Dr. Mindbender sells multimillion-dollar Cobra fortresses to Latin American revolutionaries. These “Terrordromes” emit sinister Paranoia Rays—mind-control beams that drive peaceful populations to revolution.

This fictional fortress had a real-life toy counterpart. (You can find...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in