The BlackBerry and the white whale

There’s a 2010 commercial for the BlackBerry Torch that retells Moby-Dick through a stream of websites, social media posts, and video clips. It opens optimistically, with a shot of a phone screen revealing the following message: “AT&T and BlackBerry tell a whole new story.” This claim is false, of course, as we learn immediately. A rapid montage on the phone’s screen tells the decidedly non-new story of Moby-Dick through loosely pertinent snippets of images, text, and music. The nineteenth-century whaling industry’s data-rich sea has become the data-rich realm of the internet: a compulsive phone user looks at a title screen for Melville’s novel, then decides to play Moby’s 2002 song “We Are All Made of Stars.” (Moby is supposedly Melville’s great-great-great grandnephew.) Soon we see a clip from Jimmy Neutron in which a character demands to be called Ishmael. The ensuing sequence culminates in a stop-motion swipe-through of a whale crashing through a ship, followed by “The End,” and finally our phone floating over a blank background.

Near the conclusion, lyrics from the Moby song—“People, they come together”—imply that the content accessed through the BlackBerry facilitates joyful union. Indeed, in the commercial, networked people seem to link happily to one another by sharing experiences of art. There are passages in Moby-Dick that also suggest such amiable connections amid a network that sustains a welter of data: the network of oceanic business channels whalers into each other’s proximity, but art is what brings them together. “Be cheery, my lads!” sings one character. “May your hearts never fail!” Whereupon “all follow” in joyous song. Ishmael (the narrator) and the harpooner Queequeg enjoy one another’s company while Ishmael watches Queequeg whittle. Even basic handiwork aboard the Pequod, the novel’s focal ship, has a salutary communal effect. When a whale hunt ends, and all aboard become absorbed by their shared work of whale-oil processing, Ishmael acknowledges that “an abounding, affectionate, friendly, loving feeling did this avocation beget.” At such times of utopian fraternity among the Pequod’s crew, we find sunny possibilities for people coming, artfully, together.

Still, the conclusion of the BlackBerry commercial’s adaptation—the phone’s final position in a field of emptiness—suggests a bleaker possibility: that we can lose our bearings while connecting with others through art; that compulsively following a trail of connections can bring us to a place we would rather avoid. This kind of perilous connection nearly dominates Moby-Dick. The Pequod’s tyrannical Captain Ahab deploys narrative to bring people together destructively, telling his crew the story of a whale who has wounded him and thus merits vengeance. The whalers accept that story, then follow him to their deaths. They’re susceptible to Ahab’s artistry simply because they’re like us: alone and afraid and surrounded by a bewildering array of data.

Ishmael calls these susceptible characters “isolatoes.” Pip, the Pequod’s tambourine-playing ship-keeper, sees the frightful dimension of their isolation most lucidly when he goes overboard. Alone in the water, he experiences how “the awful lonesomeness is intolerable. The intense concentration of self in the middle of such a heartless immensity, my God! who can tell it?” The sea’s specter of fearful isolation inclines the sailors to join together irrationally according to simpler forms; human invention provides vessels for sociable union to those who feel that fear, that loneliness. “Mark,” Ishmael observes, “how when sailors in a dead calm bathe in the open sea—mark how closely they hug their ship and only coast along her sides.” These mariners are poised to be prey for a would-be tyrant whose story frames the sea in a reductive but easily grasped way, and such a story is Ahab’s narrative of revenge against a representative oceanic figure artfully personified. “A wild, mystical, sympathetical feeling was in me,” Ishmael reflects. “Ahab’s quenchless feud seemed mine.”

We know what this is like. We know about lonely people brought together by a contagiously effective brand of artistry—be it at the level of craft or oratory or viral meme-mongering—that serves tyrannical purposes. We’re less aware of methods for evading those purposes, but the BlackBerry commercial at least offers some clues. By revealing the likeness between the compulsive smartphone users of this century and Moby-Dick’s Ahab-following isolatoes, it clarifies the damage that can be done by art that joins us according to obsessive craving. But it also reminds us of the amity upheld by other artistry, like that of the Pequod’s whalers. To investigate this further, to follow it into Melville’s novel itself, is to find traces of a grander consciousness, an expansive imagination that registers the various ways—harmful and helpful—in which people might come together.

Adam Colman

Death and child's play

Children dream up new uses for toys every day—a yo-yo that hypnotizes dogs! an Easy-Bake oven that tans or melts Barbie dolls!—but Frances Glessner Lee, millionaire heiress to a farm-implement fortune, was fifty-two when she began transforming dollhouses into tools for serious forensics. Her Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, a series of murder-scene dollhouse dioramas intended to train budding gumshoes in the 1930s and ’40s, asks aspiring detectives to think like children: to forget that the dolls are dolls and plunge into macabre games of make-believe based on real stories of, typically, suicide or murder. At 1:12 scale, Lee’s miniature crime scenes undo both the idealized setting propagated by dollhouses and—since the victims are mostly housewives, prostitutes, and schoolgirls—the idealized representations of beauty propagated by dolls.

Lee, who had been denied a formal college education by her Victorian parents, crafted the first diorama after they (and her Harvard-educated brother) died, as if only then could she transcend the pressure to be a lady and pursue the male-dominated field of forensics. She was not, however, a total outsider whose creativity emerged suddenly and unbidden from her unconscious mind: Lee surrounded herself with experts, including George Burgess Magrath, Boston’s medical examiner and one of her brother’s friends from Harvard, whose frequent complaints to Lee about murder investigations botched by incompetent detectives and untrained coroners motivated her to reframe criminal investigation as a scientific process. Her inspiration to renovate dollhouses into learning tools for police began to take form when she was a child, compulsively reading Sherlock Holmes, playing with dolls, and receiving a thorough education in the domestic arts.

To make the Nutshells, she applied this education subversively: she sewed and knitted clothes down to the dolls’ socks, wallpapered the rooms and added accurate blood spatters, and glazed and painted each doll with complexions and figures that varied based on expected decomposition levels. (She regularly accompanied detectives to crime scenes, taking notes on the bloating and skin discoloration of decaying corpses.) Lee approached the construction of each dollhouse the way a Renaissance master painter approached the composition process, and like they did, she had help. She hired a full-time carpenter and his son to build and furnish accurate dollhouses with shutters that opened and closed, working light switches and bulbs, and tiny keys that unlocked tiny doors. Each one cost as much to build as the average American house.

The Nutshells were crafted primarily with function instead of aesthetic pleasure in mind. They emphasize the pursuit of overlooked details. Lee wanted the viewer to find clues that would help the investigation, not necessarily solve the case at once. “The Red Bedroom,” for example, displays a bloodied ash-blond prostitute—Lee named her Marie—in a floral robe, crumpled on the floor near a closet door, her neck sliced and her head resting on a cardboard box. Her opened dresser drawers and suitcase suggest she’d been frantically packing at the time of her murder; a candy box, a jackknife, a bloodied rag, a drinking glass with liquid still in it, and two empty liquor bottles complete the scene. A smart detective viewing “The Red Bedroom” would examine the angle of the cut on Marie’s neck, review her blood-alcohol levels with the medical examiner, have the rag tested and the blood typed. Does it match Marie’s blood type or her boyfriend’s? In the statement accompanying “The Red Bedroom,” Marie’s boyfriend tells investigators: “We went to her room and sat smoking and drinking for a while. Marie sat in the big chair and got very drunk. Suddenly, without any warning, she grabbed my open jackknife—I used it to cut the string on the bottles—and ran into the closet and shut the door. When I opened the door, she was lying there just like that. I left immediately.” Is it a relevant omission that he never mentions the candy box?

The intensity of Lee’s attention to detail saves the dollhouses from pure sensationalism, turning her feminist twist on the sexist premise of the distressed damsel—or rather the dead one—into a complicated kind of art. By dramatizing females as victims, Lee fashioned herself as both victim and perpetrator. Ultimately, however, she remained in charge, not only by choosing which crimes to stage but also by withholding their solutions: if her Nutshells quietly questioned the social and political landscape, they also forced law enforcement to face—and to playact with—gruesome crimes against women. Gruesome and, in an important sense, real: Lee crafted her scenarios from composites of stories of murders, accidental deaths, and suicides gleaned from an extensive library of field books and manuals, as well as from anecdotes related to her by dinner-party guests—homicide detectives, police officers, and medical examiners—over prime rib and cherries jubilee.

The legacy of the Nutshells has generally focused on their practicality, their function. Lee organized biannual weeklong seminars that used her Nutshells as instructional tools; she even founded Harvard’s Department of Legal Medicine and endowed its Forensics Department, including the donation of her dollhouses. Since shortly after her death, in 1962, eighteen of the nineteen existing Nutshells have sat encased in glass on the fourth floor of the Baltimore city morgue, where they continue to be used to train detectives (now men and women alike). Since October 2017, though, and until the end of January 2018, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, is displaying all nineteen of them—in a show called Murder Is Her Hobby—highlighting not exactly the aesthetic pleasure they provoke, perhaps, but at least the creativity, in spirit and in craft, that brought them into being.

Jeannie Vanasco

Searching for subjectivity on Amazon

If a cat doesn’t like the furniture you’ve bought for it, you have two choices: blame the furniture or blame the cat. (Never blame yourself for raising an ungrateful cat.) Most Amazon reviewers choose the former, steering clear of inquiry into the hairy world of cat taste or into whether animals are fickle by nature or nurture: they just slap single-star ratings on the trees and castles and scratching posts that don’t delight their pets as promised. “This product must have something in it that cats don’t like!” they write. “Our cats wouldn’t touch it, our friends [sic] cats wouldn’t touch it, and their friends [sic] cats wouldn’t touch it!”

I know all of this intimately, unfortunately. For half a year, as a researcher for a start-up incubator, I was tasked with trawling Amazon for some insight into what people like and don’t like. I’d sit—back to the window and face to the screen, sunlight bouncing off Lake Michigan’s corduroy waters and onto my shoulders, an occasional horn twenty floors below piercing the murmuring air conditioning—and I’d click. For breaks, I’d browse books and music on the site, something I’ve been doing since I was fourteen or fifteen, when I’d just discovered Iron and Wine and couldn’t believe there were similar bands out there, let alone that a website could tell me who they were. I’d study strangers’ wish lists and click through “Customers who bought this item also bought” recommendations until they led me back to where I’d started. In the background, I’d download the albums on LimeWire, watching the progress bar slowly fill in as I scratched and scrubbed my pre-calc homework into a neat, orderly record of the steps I had taken and where I had gone wrong.

Cat furniture is not art, no matter what reviewers suggest. But online it is sold alongside art—that is, music and books—and rated on the same scale. “That a site like Amazon sells virtually everything tends to blur or flatten things,” writes Tom Vanderbilt in You May Also Like: Taste in an Age of Endless Choice, a book that draws on experiments, studies, interviews, and historical texts to trace our tastes to their hazy origins, from the personal to the communal, showing how what we like both is and isn’t up to us. If Vanderbilt can be said to reach a conclusion, it’s that we may know what we like, but we rarely know why. “We are, in effect,” he writes, “strangers to our tastes.”

So we turn to others. And when we do, our grasp of what we like is mediated by algorithms—increasingly so, as our consumer and artistic habits both hew toward society’s insistence on measuring everything, subduing it into objectivity. When I buy something on Amazon, I get the benefit, or the downside, of having my purchase generate the information to which Vanderbilt’s title alludes: what I might also like. In other words, what I may buy next. (According to Amazon, customers who bought Vanderbilt’s book in hardcover also bought Pretentiousness: Why It Matters, by Dan Fox; Vanderbilt’s previous book, Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do (and What It Says about Us); and Jessica Helfand’s Design: The Invention of Desire.) My purchase is valuable not just because it makes Amazon money but also, and more important, because it points in the direction of another purchase.

The more art is packaged by the “recommendation” cottage industry, the more it risks becoming the avenue to enjoyment rather than the endpoint. Thanks to our algorithmically driven online economy, we may enjoy art only when it serves to reveal other art we might enjoy; we can enjoy art only when an algorithm makes it objective that we should, or at least assures us that it conforms to our preordained genre loyalties. There is a tension, therefore, between the subjective and the objective, between experiencing and rating the experience. On Amazon, it can be easy to lose sight of the intrinsic feeling of art, to become a consumer of art focused on seeking it out rather than actually spending time with it. Off Amazon, the same threat remains, both because of the ever-dwindling number of things not available on Amazon and because the relentlessly quantitative mind-set of the site has seeped into everything around us.

Even so, when we look at art to figure out which art to look at next, the point remains the same: to experience subjectivity. It’s how we reach that subjectivity that’s changing. Before, we allowed our tastes to remain mysterious, or at least unquantified, which tended to reinforce them. “It is striking to realize how strongly we stand by our likes and dislikes given how open they are to distortion and manipulation, as much by our own brains as by outside influences,” Vanderbilt writes. “Perhaps we instinctively sense the fragility and arbitrariness of these preferences, and so cling to them even harder.” And yet numbers, far from exposing that fragility, allow us to hold on even tighter. We expect a lot from numbers; we expect them not to raise questions about our tastes but to answer them. Vanderbilt confesses that he once “rigorously trained” his Netflix algorithm because he “wanted it to know not just that I liked something but why I liked it. I wanted more than it could give.”

That is, he wanted to uncover his own subjectivity through objective means. The tension is the same: as I search, I both do and don’t want Amazon to be able to pin me down. I want to know my tastes, but I also want to be able to be as surprised as I was when, in fifth grade, I found myself endlessly replaying an Alanis Morissette CD despite being sure I didn’t like women singers. I want to know what book to read next, but I want to stop thinking about it while I’m still reading something else. I want to be sure of what I think about art—that the woman in Nighthawks makes me cry and that there’s a particular beige that Matisse often used that makes me want to throw up—but I want that art to trigger subjectivity, even ecstasy, a feeling that precludes art serving any purpose other than getting me to live in the moment, if you’ll forgive the cliché, rather than in the self-conscious experience of the experience, where I’m too busy categorizing and surveying to actually notice that I’m happy.

It would be naive to suggest that the solution is to consume art offline, far from reviews of cat furniture. It would be naive, too, to suggest that there’s a solution at all, that this is something that even needs to be solved. Art maintains itself by reinforcing the viewer’s subjectivity, even when that viewer insists on measuring and reviewing—even when she turns into a consumer. Perhaps we wrestle with this duality within ourselves more than ever before. But tastes change: in fact, as Vanderbilt points out, this is one of their surest characteristics. And art is too unruly to be reined in. We see the triumph of art over algorithm every time our tastes—“fleeting,” Vanderbilt calls them—morph into new ones, no matter how sure we were of our most recent five- or one-star rating. May we keep failing to produce indelible measurements, may we turn to our cats to opine purely when we don’t know how, and may the tension remain taut between the measured certainty of recommendations and the unmeasured uncertainty of our reactions.

Rachel Z. Arndt

Run-of-the-mill sticks, run-of- the-mill stakes

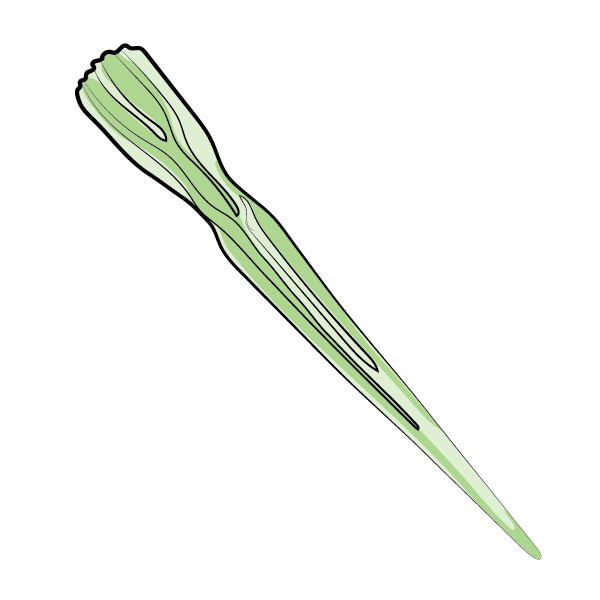

If you are, or ever were, a serious fan of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, you may know that Mr. Pointy was Buffy’s favorite stake. She kept it beside her when she slept, like a sharp wooden security blanket, and cracked jokes about it the rest of the time. You might also remember that Mr. Pointy originally belonged to the Jamaican American slayer Kendra Young, who was introduced and then killed off in season two; you can, if you want, think of the stake—brought from the black diaspora by a black girl who made it herself to a white girl who then cherished it as her own—as a symbol of cultural appropriation.

You can also use Mr. Pointy, as many viewers use Buffy, to make other points: it is a symbol of girls’ empowerment, a comically phallic object that only a powerful woman can ever wield; it’s also a way to remember that serious claims and extended allegories about sex, power, skill, and patriarchy hold the potential for comedy. The stake is both a verbal and a visual pun. Unlike Buffy’s run-of-the-mill stakes, made from run-of-the-mill sticks, Mr. Pointy has visible whorls and curves—it is, in other words, like the show’s fandom, not quite straight. (The character Willow had yet to come out as lesbian or bi when the stake first appeared.) Sarah Michelle Gellar, who played the title character, said in 2015 that she took Mr. Pointy home from the Buffy set; Buffy, the character, once said she’d had the stake bronzed (which would have rendered it ineffective against vampires). Transformed from weapon to trophy or souvenir, Mr. Pointy is like the knife in Elizabeth Bishop’s “Crusoe in England,” or the disassembled hammer in Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time: when deprived of its original utility, its original point—killing vampires—it becomes fit for contemplation, what Heidegger called the present-at-hand.

And yet—unless you know what to look for, know it by name, recognize its slight curve—Mr. Pointy looks like any piece of wood such as you might use for a garden fence. Similarly, unless you’re already a fan, many Buffy episodes might look and feel like episodes of other superhero or supernatural-teen TV shows. Fans make fine distinctions and sustain long arguments about the meaning, use, and importance of TV shows (and comics, and novels, and poems) in which, to outsiders, not much is at stake. For them, though, the show is its own reward for being, its own point—or else it has helped make a point that would otherwise have been harder to see.

For many Buffy fans the point was pop-culture-friendly, teen-oriented feminism. The show arrived on TV soon after the Riot Grrrl movement, during the optimistic 1990s, when many non-techies—many of them teens—could live online for the first time, forming communities not mediated by teachers or authority figures or the speed of US mail. Some of these communities embraced the show and its consistent messages: you, too, might discover your hidden powers; teen sexuality might be dangerous, but it’s not something adults can control; if you want to slay demons, get help from your friends.

Those messages helped make creator and show-runner Joss Whedon famous as a straight man with a feminist message, an adult guy whose work could empower women and girls. Joss, as his fans learned to call him, would go on to cocreate four more TV series, including Firefly and Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.; well-regarded X-Men comics; a black-and-white Shakespeare film; the delightful web-only musical superhero satire Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog; and 2012’s The Avengers, to date the top-grossing superhero movie ever. Earlier this year, though, Whedon’s rejected script for Wonder Woman hit the internet, where it was widely panned as a straight-male fantasy; this summer, Whedon’s ex-wife, the architect Kai Cole, alleged in an open letter that Whedon “hid multiple affairs… with his actresses, co-workers, fans and friends” over their fifteen-year marriage. Cole’s letter suggested—without quite stating it—that he was sleeping with several much younger, and by definition less powerful, female employees. Marriages (and opinions about them) differ, and it’s often a mess when they end, but Cole’s letter frames Whedon decisively as not, in her words, “one of the good guys.”

After such knowledge, what forgiveness? The premier Whedon fan site promptly shut down. “Nobody wants to see their heroes crash and burn,” remarked pop-culture critic Gavia Baker-Whitelaw. But maybe we saw this point before it hit home. It’s hard not to ask whether Whedon—like plenty of geeky guys before him—set out to celebrate strong women in part so they would like him, and sleep with him. Is that so wrong? It sure is if they work for you.

And yet it’s also wrong to consider Buffy—a show that had many actors, and many writers (Marti Noxon, for example), and many virtues, from the sexy bits to the cowritten musical episode—coterminous with Whedon. No films, no TV shows, and very few comic books are the work of one artist alone. At the end of the show’s seven-season run, in an episode Whedon wrote and directed, Buffy ceases to be the slayer; no one knows how many girls get the powers she once held, but it’s certainly a lot. It’s as if the show had asked us to find new fandoms and new heroes, and never to put all our trust in any one person or thing. If you can’t see Buffy without seeing Whedon’s mixed motives, without asking what one creator wanted, you might be right. But you might also be missing the point.