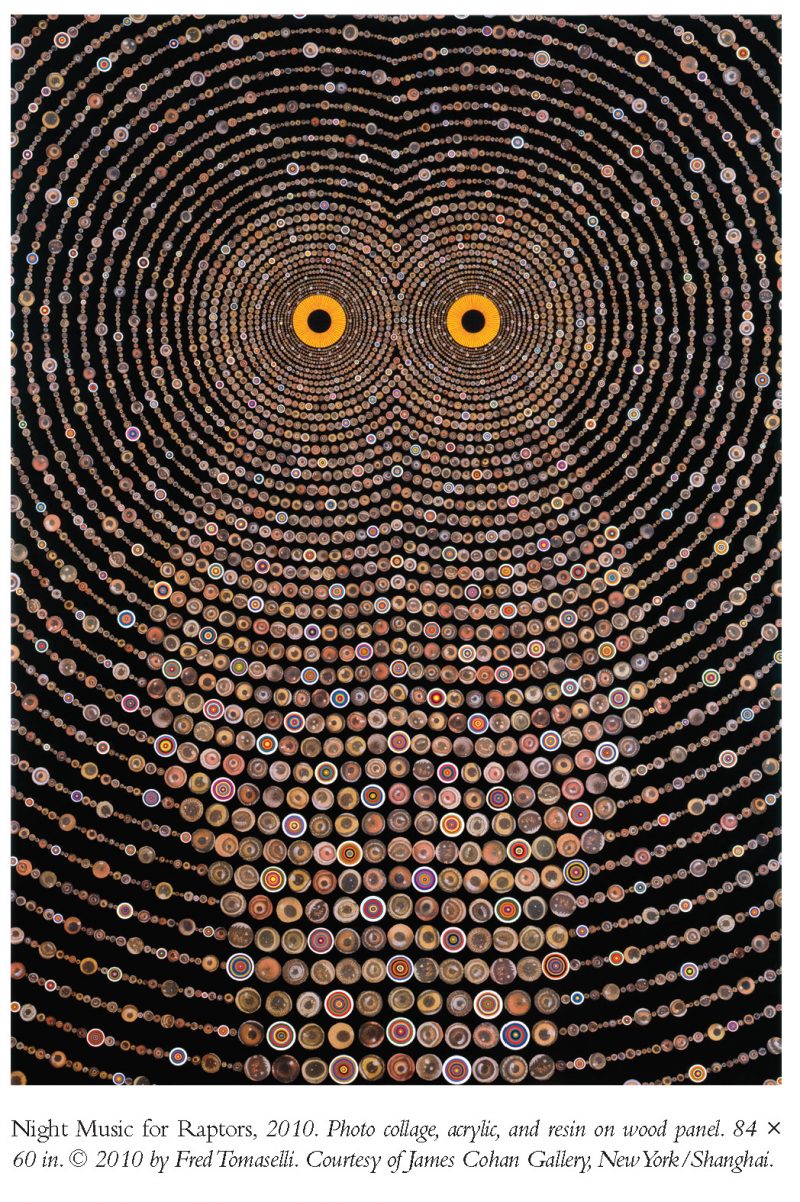

The world according to Fred Tomaselli is a dark, druggy, visually lurid place: a swirling dazzle of eye-popping data. Influenced equally by SoCal surfer culture and New York City trash-punk, Fred’s best-known work—highly detailed, post-pattern paintings incorporating prescription pills and hallucinogenic plants under a protective layer of resin—grapples with deep, philosophical questions like “What is consciousness?” and “Is perception real?” More recently, as in Night Music for Raptors, he’s meandered deeper into a natural world of flora and fauna and, well, owls, as I found out when we met at his studio in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn.

—Alec Michod

Night Music for Raptors

THE BELIEVER: Night Music for Raptors, like much of your work, must have required meticulous work to make. FRED TOMASELLI: It was a bit labor-intensive, and the four-month process was sometimes mind-numbingly repetitious, but that’s what I had to do in order to see what I needed to see. I began the piece by plotting out the two points that formed the center of each of the owl’s eyes. I then set up a mathematical system of expanding circles, which became the armature for thousands of photographs of birds’ eyes. Then I started gluing them down. I made micro-decisions along the way, but not as many as I made on the piece that came right before it.

BLVR: This painting emerged out of another one?

FT: Night Music was very different from the piece that came before it. That work, entitled Starling, arose out of the chaos of an abstract-expressionist background. I was splashing and slashing paint all over the panel and not knowing where I was going. Eventually, an image emerged, and even though I was satisfied with the end result, the whole process made me feel sort of mentally ill. Night Music was a way to calm myself down. Also, I was in the middle of prepping a twenty-year museum retrospective, which gave me a reason to revisit my geometric, minimalist work from the early ’90s. I noticed how, over time, my work had become increasingly dense, narrative, and imagistic. I wanted Night Music to be a kind of bridge between my earlier work and what I was doing now. I came upon this idea of making this owl out of two conjoining sets of concentric circles, and then having them radiate out to fill up the space of the picture. The two big eyes, incidentally, are the same size as two LP records, and I imagined them as two turntables seen from above.

BLVR: There’s definitely a spinning quality to the image.

FT: Right. I wanted to embed multidimensional information into very simple geometry. I like to think that these thousands of eyes simultaneously became the feathers of the owl, two turntables, the starry night sky, and musical notation. The rhythm of the concentric circles felt musical to me, and conjured up a sense of the visualization of sound, of synesthesia. It’s both a hooting bird of prey and a party that’s alive with sounds of the night. It’s also a painting that returns the viewer’s gaze. I wanted a feedback loop circulating between object and viewer—of looking and looking back. I also wanted it to have a very confrontational scale, and at seven by five feet, that owl is a monster that could really kick your ass.

BLVR: When you’re making something like this, do you change your mind a lot? Does the image go through different mutations?

FT: A lot of people suspect that everything I do is plotted out ahead of time, because of the pristine nature of the finished work. They think I know what I’m doing, but, honestly, I really don’t. I scrape things off, paint things over, drill things out, and generally muck around until it feels right. I then hide the evidence of that struggle. That being said, Night Music for Raptors had fewer changes, because of the mathematical nature of the composition. It did, however, turn out a lot denser and more hypnotic than I ever expected. One of my favorite things about making pictures is not knowing what I’m going to see until I make it.

BLVR: And that happened with this painting? You didn’t know?

FT: Sometimes you start making a thing you think you want to see, and you end up making and seeing something very different. The journey from a fuzzy idea to a concrete object is always full of surprises. I was surprised, for instance, by how this piece gathered intensity through the density of form. But I was less surprised by this one than some other works. I mean, in the past I’ve started works that were intended to be simple abstractions, and then I hit a crisis, and the next thing you know, figures emerge along with references to Don DeLillo, alien abduction, and biblical themes. You just can’t plan for stuff like that. It seems like all the big changes in my work are a result of disasters that need radical surgery.

BLVR: The eyes—how did you decide which eyes to put where, and which eyes to paint over?

FT: Each eyeball has a slightly different color combination, shape, and size. I began by laying them out very intuitively. If they didn’t work out, I figured I could always paint them over, and I did. I was trying to create a notational scale in the work through chromatic juxtapositions that sort of felt like music to me.

BLVR: I definitely get a very musical vibe.

FT: I wanted it to feel harmonious, and those kinds of decisions are almost all intuitive. When I’m working like that, there’s no system anymore—it’s just me vibing the work. In this work, I decided not to resin over the final painted passages. This was a big deal for me, as I’ve always insisted upon encapsulating the real things, the photo-collage and the paint, under a final coat of resin. I liked how it flattened out the image and made it a little harder to ascertain the nature of the picture’s reality. The resin also had a tendency to give everything a slight yellowish hue. But by leaving the final paint passages on the surface, I gained a brighter chromatic spectrum. Without the final resin overlay, these bright little target shapes, which mirror the structure of the photo-collaged eyes, really popped. I think it makes the work a little more dynamic, and it allows the viewer to see the “touch” of my paint. I think this new reliquary of my touch allows people another way in. And it’s something I’ve continued to do in my subsequent work.

BLVR: The eyes painted over the resin are the way in?

FT: One of the ways in. Look, my work has always been very handmade, but the slick, shiny resin coating gives it an almost machine-like perfection. I found that leaving the hand-painted passages on the surface warmed things up a bit. You see the paint when you’re close to the work, but there are a variety of vantage points that offer a variety of experiences. There’s a thing you can recognize from across the room—an owl. That’s the image, but then, as in pointillism, as you get closer to the work it breaks down to its individual bits. Then you get in a little closer and you find little images again. Move in closer and you see the little targets painted on the surface. As the viewer moves from side to side, the upper images and their shadows shift around due to their various depths within and above the thick resin. The image isn’t stable, and shifts shape and meaning depending on how far away and where the viewer is situated. By the way, none of these experiences are observable in reproduction. You have to be in front of the real thing for a real experience.