The paintings of Eddie Martinez contain a grunting, primal urge for mark-making. With a slew of tools and techniques, he piles up canvases with chunky shapes and smears that appear simultaneously accidental and blithely confident. The layers of his work go deep, and a nice, long look at a Martinez image reveals an idiosyncratic history of art: cave paintings, still lifes, animation, art brut, children’s drawings, and graffiti are all stacked and spread into an undeniable slab of satisfaction. Eddie and I spoke at his studio, in front of an exhibition’s worth of new paintings.

—Ross Simonini

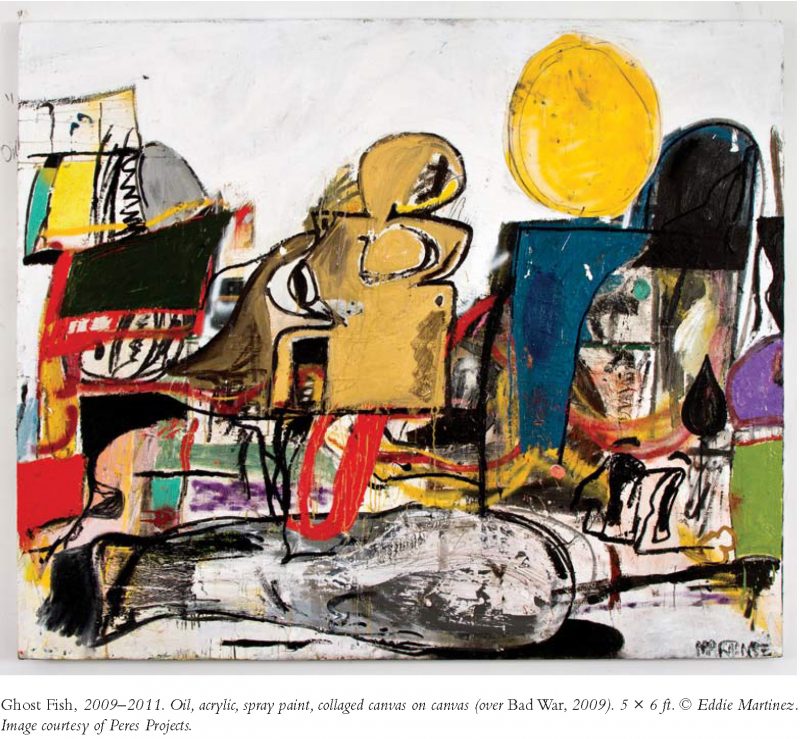

Ghost Fish

THE BELIEVER: This one’s great.

EDDIE MARTINEZ: Yeah, I’m happy with that one. I’m suddenly interested in trying to figure out if my drawings translate into large-scale paintings. This is starting to feel pretty drawingish to me.

BLVR: What do you mean, “drawingish”?

EM: Like the weight. It’s impossible to take a drawing and just say, I want to make a five-by-seven painting. I’m not saying it’s impossible. But for me, in my process, I haven’t figured it out yet. So that’s why I’m constantly trying to replicate it—how do you make a pen line out of that same weight of paint? How does that translate? So I’m playing with different-sized brushes and different motions. It’s starting to get there. I feel like my drawings are more successful, quicker. And they’re easier to make. It’s not about someone else looking at it and saying, “Oh, that’s like a drawing.” It’s about me looking at it and feeling it’s natural.

BLVR: You said that this is your most abstract painting.

EM: Yeah, not ever, but out of this body of work it is. I don’t know, I’m just really enamored of that painting. I feel like I’m doing some things there that I’ve been wanting to do.

BLVR: Could you say what those things are?

EM: Um, I like that collaged sun. That raw-canvas collaged sun. It’s just like raw canvas with a little bit of paint on it. It’s dusty, so it really looks collage-y to me. It has that faint charcoal line. You can see the sheen and the white. And then it’s just really flat. It just feels like the definitive collage move. It feels abstract to me.

BLVR: Are you trying to get the feel of collage with a whole painting like this?

EM: No, I’m never trying to replicate that. And I’m not trying to make it look like a drawing, either, ’cause I could just make a large-scale drawing. I could make five drawings while we’re sitting here. Doodles. And I might really like one of them a lot. And so how do I get that with a painting? I just want to like the paintings as much as I like the drawings.

BLVR: Would you say artists like, say, de Kooning, got at that?

EM: Where they’re super-confident. And I guess that’s what I’m really talking about with the drawings. Because it’s just second nature to me to make a drawing; I don’t really think about it.

BLVR: But paintings aren’t really like that? They’re so much work.

EM: They are. There’s just a lot more involved in a painting this size.

BLVR: Did any of these elements come out of drawings specifically?

EM: Yeah.

BLVR: Because it feels like with a lot of your other drawings there are certain visual tropes that reappear— a vocabulary.

EM: Repetition always comes from the drawing. Like the eyeballs down there. There are a few eyeballs there. The little, like, raindrop-teardrop thing—that black one above the eyeball. But I don’t want the painting to rely on the repeated symbol. I want it to be more about the painting and the process.

BLVR: I like the repeated symbol as a way of connecting all your paintings.

EM: I do, too, but with that painting in particular I pushed it—that’s why it feels more shape-based, less representational. I don’t feel like I’m ever going to be an abstract painter. I’m never going to be a purely representational painter. I just want to keep it open.

BLVR: Why did you call it Ghost Fish?

EM: That shape on the bottom.

BLVR: Is that how most of your work is titled, an image that calls to mind some words?

EM: Yeah. I think so. And just from words floating around in space.

BLVR: It’s like you’re choosing words, but nobody can quite see the connection, so the words don’t get in the way.

EM: I don’t want that to happen. Not anymore. That was easier and more accepted to do for a while, but now I feel like a part of the evolution of the work is also the titles. You can’t keep naming them like, I don’t know, whatever goofy shit I used to name them.

BLVR: Like what?

EM: In 2004 I named a painting—it was a little guy with a bottle—Tubular Bro. Which is fine, I don’t want to totally lose that, but now, as the paintings become more mature to me, and I work harder on them, the titles go along with that.

BLVR: How long did you work on this one?

EM: I worked on it for a summer; these are all summer and fall.

BLVR: In about four months you made an exhibition’s worth of paintings?

EM: I made these in much less time than I need now, actually. I worked up in Massachusetts for the end of the summer. My in-laws have a house in Massachusetts, and there’s a barn there, and we built a studio there in 2008. I went pretty hard-core in August—like, every day, all the time. ’Cause my bedroom’s attached to the studio.

BLVR: So when you say “all day,” is that nine to five?

EM: I’m just not that kind of artist. I don’t know how to do that.

BLVR: It’s more just like off and on throughout the day?

EM: Well, it’s off and on, but sometimes it could be eight hours straight. I don’t have a schedule. I can go up, you know, have a cup of coffee, make a few moves, and that could be the whole day because those moves really push the painting. And that’s fine. Some days I could be in there for ten hours. Anything goes.

BLVR: So you don’t feel like you have to have selfdiscipline about the way you work.

EM: No, because I love working. It’s all I really want to do, make paintings.

BLVR: You use oil paint, spray paint, acrylics…

EM: Yeah. It’s just about tools. It’s just about markmaking and the different marks you get from different tools. The spray paint’s been pretty subdued in this one. It’s pretty pushed back—the red and yellow in the background there.

BLVR: You’re painting over it a lot.

EM: There’s a lot of layers in all the paintings.

BLVR: How did this one start out?

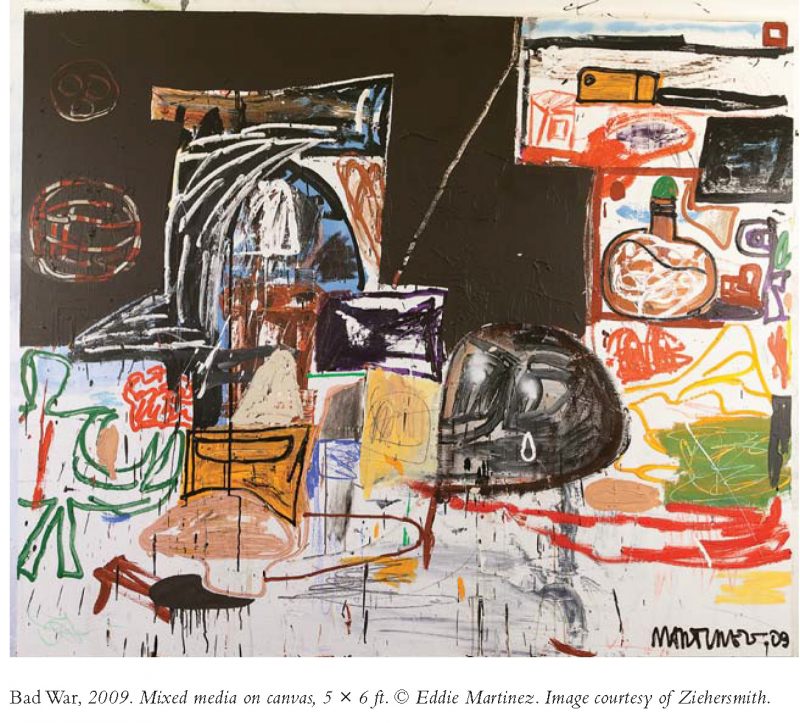

EM: Well, underneath that is a painting called Bad War from 2009 that I exhibited in my last show in New York. And then I just went over it.

BLVR: Can you see any elements of that one underneath?

EM: Yeah. I had it in my house for a little while, and then I just didn’t like it. It was just sitting there—a fiveby-six canvas—and I was like, “Let’s do a little work on it.” I think the purple is from that. I just didn’t feel like there was any point in holding on to it, because I didn’t feel like it was that great of a painting. And I had already showed it and it was a big canvas and they’re expensive and why not push it further?

BLVR: So is this connected to that painting in any way? Or are you just reusing the canvas?

EM: Well, it’s connected in the sense that what was there was the starting point for this painting. So some of that stuff was still there, and it must have, during the process, affected decisions. Because I didn’t white it out. If I were to just white it out, and then make a new painting, then you’re just using it for the canvas. But if you’re just going over it with what’s there, then that’s probably affecting it.

BLVR: Was the original abstract?

EM: Ish. It had that skull and I think that was about it.

BLVR: The skull, where’s the skull?

EM: Well, that eyeball. That little white shine in there, to the right of the yellow image.

BLVR: It has almost, like, a bird shape.

EM: Yeah, that has a real birdy look and feel to it. [Long pause] It excites me.

BLVR: When you’re making marks, are you trying to move your brush in new ways?

EM: What I’m doing is using whatever’s in front of me, and sometimes that’s a knife, sometimes that’s an actual brush—it’s just about getting it on here as soon as it comes out of my head.

BLVR: Does that mean you usually have an idea for something and then you put it down?

EM: Nothing’s really plotted out. I just start the thing.

BLVR: Do you try to avoid habits?

EM: It’s not even avoidance or anything, it’s just about keeping myself satisfied and feeling like I’m progressing and moving in a forward direction and not going backward and feeling sad. It’s all it’s ever about. Just about me being excited about what I’m doing, because obviously it’s exciting to be able to be in the studio and make what you want to make. But even that’s not enough, it’s never enough. I still want to make paintings that give me a boner.

BLVR: And would you say all these new paintings give you a boner?

EM: In different ways. It’s always about doing something new that feels like I made it, but it’s still new, it feels like I’m pushing the boundary a little bit of what I’m normally doing, and then feeling successful.

BLVR: And out of curiosity, when you say something “new”—

EM: It could be a color, it could be a collage element. There’s so many subtleties and different little things that are happening. And even if it’s just—like, the sun is a new thing. So now I’m sort of exhausting the sun, and that came from going to Jamaica and sitting in the sun, which sort of ties into the narrative thing, telling a story that’s connected to my life. All of a sudden the sun is showing up in the paintings because I was sitting in the sun for so long. I was drawing all day on the beach and I was drawing these suns and I felt that it was going to be a new element in the paintings. You know, it’s really as simple as that.