Hilary Harkness’s most recent show at the Mary Boone Gallery depicted, in six paintings, the relationship between Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. In her three solo shows leading up to this one, Harkness’s paintings were marked by World War II battleships populated by dozens of meticulously painted women—sometimes naked—interacting with each other in sometimes-lewd, often-complex ways. She has taught at the Yale Summer School of Art and Music, and blogs about art-making for the New York Academy of Art. Her work has been exhibited worldwide.

—Sheila Heti

THE BELIEVER: Tell me a bit about Alice at Loggerheads.

HILARY HARKNESS: Well, Alice is sitting at a table; the shells are placed upside down, and one is being used as an ashtray, symbolizing her relationship to her fertility. There’s a Picasso portrait of Stein kind of looming behind Alice that’s meant to look like a shroud, because you can only see the outline of Gertrude. I think Alice was a tremendously talented person who used her talents to aid Gertrude; she lived in support of her and she was kind of laughed at by history.

BLVR: Have you painted historical figures before?

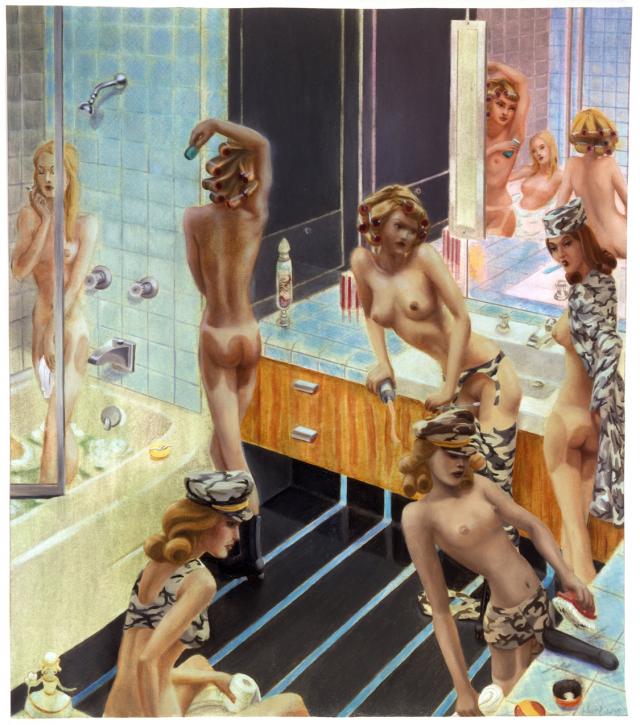

HH: I started out painting cross-sections of buildings and battleships. This is my first attempt at portraiture. I’m kind of known for paintings with lots of small figures in them, so my goal was to paint more medium-size paintings with larger figures interacting.

BLVR: Why did you choose to paint Alice in this attitude?

HH: I suppose because of stuff that was going on in my own life. I was in a complicated relationship with a woman I loved dearly; however, it never became clear if I related more to Alice or to Gertrude Stein. It wasn’t a one-to-one correlation with my life in any way. I think I conceived of the painting in a moment of anger, or of extreme distress. It came to me.

BLVR: The image came to you in your head?

HH: Yeah. I’m really interested in domesticity. It’s a big part of my life. I do not conform to the artist archetype of the lonely creator. I have a fairly normal life, and I feel like I have to have it to be creative. For instance, I paint in my kitchen.

BLVR: Why do you need the domestic in order to be creative?

HH: I feel that when I get too removed from the world—I think every young artist goes through that thing where they paint all night long and have a solitary existence for a while—but I think for an artist to make something transcendental, it has to in some way be related to reality, so an artist has to be interacting with people, or the world, in some kind of way.

BLVR: When you had this painting come into your mind, how soon after did you put something down on paper?

HH: I’m really slow. It took me quite a while to draw it. I wasn’t sure if I was ever going to be able to sell it—or ever have a career again! Because I was changing directions, and because I was painting dead lesbians! But Mary Boone is really great for artists, in terms of letting them do what they need to do, and understanding that they go through changes, and that everything is just a stepping-stone to something else.

BLVR: Can you tell me more about these changes you’re talking about? You said there was a change from painting small figures, but it sounds like you’re talking about something even broader than that.

HH: I didn’t have a girlfriend for many years, though I wanted one, and I suppose, subconsciously, maybe out of that particular loneliness, I couldn’t help always painting these whole elaborate worlds in microcosm that were populated only by women—like, two hundred women in one painting. I don’t know. Just too many. Then in 2006, I fell in love with an amazing woman who became my girlfriend for many years. So instead of painting a million women in the world, it turned into painting just one or two. I just couldn’t paint from the same place anymore, because my reality had changed.

BLVR: I guess the relationship between any two women is so complex in truth, that if you’re living a reality close to that, to think about two hundred figures is just absurdity, you know? Perhaps that lack of emotional complexity can only exist in fantasy.

HH: I agree with you.

BLVR: Can you just talk a little bit about Bride of Stein? Can you take me through the painting?

HH: The artworks depicted behind Gertrude and Alice were owned by Gertrude Stein. There’s a Tahitian by Gauguin and there’s a Matisse painting, Le bonheur de vivre. The wallpaper really belonged to them. It’s a wedding portrait of sorts. Alice is overjoyed by what she thinks is her good fortune, but Gertrude is kind of paying more attention to the dog that is jumping up in the corner. Gertrude was very independent. Also, when Gertrude died, there wasn’t an adequate will, and Gertrude’s relatives took nearly everything. Alice was left penniless and survived for two decades longer, broke and at times unable to afford heat. So it wasn’t, as far as society goes, a real marriage. So her happiness is short-lived.

BLVR: Did you seize on their relationship after doing a lot of thinking about, Maybe I’ll paint them, maybe I’ll paint other people, or was it pretty much like, I want to paint them.

HH: I had to paint them. I had actually considered painting Peggy Guggenheim first, but she was abused by her first husband, and maybe others, and if she was being attracted to abusers—I’m not ready to go there. Maybe in the future.

BLVR: Right. So you were saying about Alice—

HH: I actually see her as a monster who didn’t know her own strength. She didn’t know her own power.

BLVR: How come Alice is a monster? Why would you call her a monster?

HH: It’s just a feeling from things that I’ve read. I think a dynamic developed where Gertrude was extremely gregarious and her energies were very scattered in many ways, and Alice was stuck in the position of being the wife of a famous person, so she became a guard dog of sorts, controlling access to Gertrude in some ways. I think in many ways society has perceived her in a negative way, so I’m trying to deal with that. I wish the paintings could offer something transcendental, like about how she overcame her lot in life. Some people might say, “She was married to a wealthy woman, what did she have to complain about?” I feel like I haven’t been able to redeem her in any way.

BLVR: But this picture of her, this bridal picture—I mean, she doesn’t seem unredeemed here. I would project a feeling of eventual pain or something, because, as you say, Gertrude Stein is looking at the poodle. So, if anything, it’s Gertrude Stein in this picture who is, to me, more the monster. I mean, to deny affection, real affection—

HH: I guess you could see it that way. I hadn’t really thought of it, because some of the other paintings are about Gertrude, speculating on how she cheated on Alice. Though I have no doubt that for the most part she was devoted to Alice, and that she indeed regarded her as her wife.

BLVR: There’s that one where she’s in the room with—

HH: The minty green painting where she’s in the room with the redhead? Yeah. Fame came to Gertrude relatively late in life. I don’t know how she managed it. Also, I think she’d had a ménage à trois or something with two other women, in her early years, before Alice.

BLVR: Let’s just look at one more, Pleasing Papa. Now, on the far right, is that supposed to be Alice?

HH: Yes.

BLVR: She’s sort of left out of the whole scenario of the conversation between Hemingway and Stein.

HH: Yeah. I usually have her dressed in green for envy. Hemingway was Gertrude Stein’s protégé, and I think he’s on the record as wanting to sleep with Gertrude. He found her immensely attractive. But she was a stone butch, meaning that she didn’t let people touch her—she did the touching. Also, Hemingway revealed to the world intimate details of their relationship, making her sound pretty horrible—like, he recounted a terrible fight between them. If he had this enormous sexual response to Gertrude, I wonder how he treated Alice. So Alice is the femme in the kitchen. I have her as decapitating him in another painting.

BLVR: I remember that one from the show.

HH: Yeah, there’s two decapitation ones. [Laughs]

BLVR: And why do you always show her breast?

HH: I show her breast?

BLVR: Well, in Pleasing Papa, and in Alice at Loggerheads there’s also the one breast.

HH: Oh. Well, in that one I wanted to show the hickeys on it. In many ways she’s having a great relationship, but there was just something missing for her.

BLVR: It’s funny, because in all the pictures it just seems like Gertrude Stein is the… if anyone is the monster it’s her, because here she is ignoring Alice at the bar with Hemingway. Alice almost seems like the accessory. Then she has this affair.

HH: I accept your interpretation.

BLVR: I’m only bringing it up because you said to me that you relate to both of them, but that you identify one of them—Alice—as the monster.

HH: Well, I’m no longer in the relationship I was in when I painted these paintings, so it’s like a body of work done within one relationship. I was devoted to my girlfriend, but I’m also a very confident and driven artist, and a deeply flawed person, besides. I don’t like to be dominant in a love relationship. You know, I identify as a femme, in that I enjoy a supportive role and enjoy wearing high heels, but I think painting is ultimately my master—that bitch. [Laughs] It’s hard to have a relationship if I’m not sleeping because of deadlines.

BLVR: I don’t know why I’m taking this train of thought—just because I’m interested—but if I were making these paintings, because I’m such a guilty person, if I related more to Stein, I would on a conscious level think Stein is the monster. I would feel this guilt about having success and ignoring my partner.

HH: Stein’s love affair was with the entire world. It extended beyond Alice. Alice had Gertrude, and Gertrude had everyone! So what happened to the extra energy, for Alice? Did it become ingrown, somehow? I don’t know.

BLVR: It’s interesting. I talk to many artists and writers, and I always like when artists are transparent about the relationship between life and art. Sometimes people can be completely private about this, like they won’t say anything. I feel it’s strange when artists have something to hide. There’s so much mystery in art, it’s not as though you can ever say so much that the mystery is dispelled, you know?

HH: Are you saying that even though I’ve talked a lot, I haven’t gotten rid of the mystery of the work?

BLVR: Yeah, not at all. For me, there’s more mystery than there was before; much more.

HH: That’s great! That’s perfect! Because I don’t know why I’m called to paint what I paint. It’s just what comes out, and halfway into this body of work I was getting a lot of negative feedback from people in my life, so I tried to do other things and I became blocked. Very unhappy. I started four paintings I couldn’t finish. I lost maybe six months of my life to trying not to make this body of work that, in the end, demanded to be made. [Laughs]

BLVR: So how long did it take, beginning to end?

HH: Let’s see.… I had a show in 2008, and there was one Alice painting in that show. I would say it started probably late in 2007? Oh no, it started in the summer of 2007, because I remember having my mother pose for Gertrude.

BLVR: Had your mother ever posed for you before?

HH: No. [Pause] If I think of Gertrude as my mother, I’m in trouble! [Laughs] There’s still one unfinished one that’s just, like, sitting in my closet.

BLVR: Are you ever going to finish it?

HH: I’m not sure. I don’t think it would be the most attractive image, really.

BLVR: What do you mean?

HH: I was thinking of Duchamp’s piece Fresh Widow, which was a play on “French window.” Duchamp took a window and blocked out the panes of glass with black leather. I thought about reworking his idea and taking it back to just being a window through which you could look to see the garden of the ladies’French château, with a disappointed Alice in evening attire in the foreground, and an insane Gertrude in the distance, dancing with her poodle, Basket. It would be set shortly before Gertrude’s death.

BLVR: Why don’t you finish it?

HH: It could just be that I’m waiting for the technical ability to paint it. I feel like I can’t pull it off right now. It’s so sad. I almost feel protective of it.

BLVR: In what way?

HH: I don’t know. I feel like if I make a painting really well, people will take care of it and not throw it out, but I’m not sure how this painting would fare in the world.

BLVR: You think people would throw it out?

HH: I’m sorta kidding about that, but I used to have that fear back when my paintings were only selling for a couple hundred dollars. It’s not that far from a gallery to a garage sale.

BLVR: That reminds me of Picasso’s Les demoiselles d’Avignon, how he kept it in his closet for a long time—

HH: Oh, really!

BLVR: —and didn’t show it to anybody. Oh, yeah!

HH: Oh!

BLVR: I think he kept it there for nine years.

HH: [With relief] Huh!

BLVR: He painted it and he said, “It’s too ugly to show anybody.” So he just kept it in his closet for years and years.

HH: Wow. Well, I hope I can finish this painting, and that it can go out in the world and be loved!