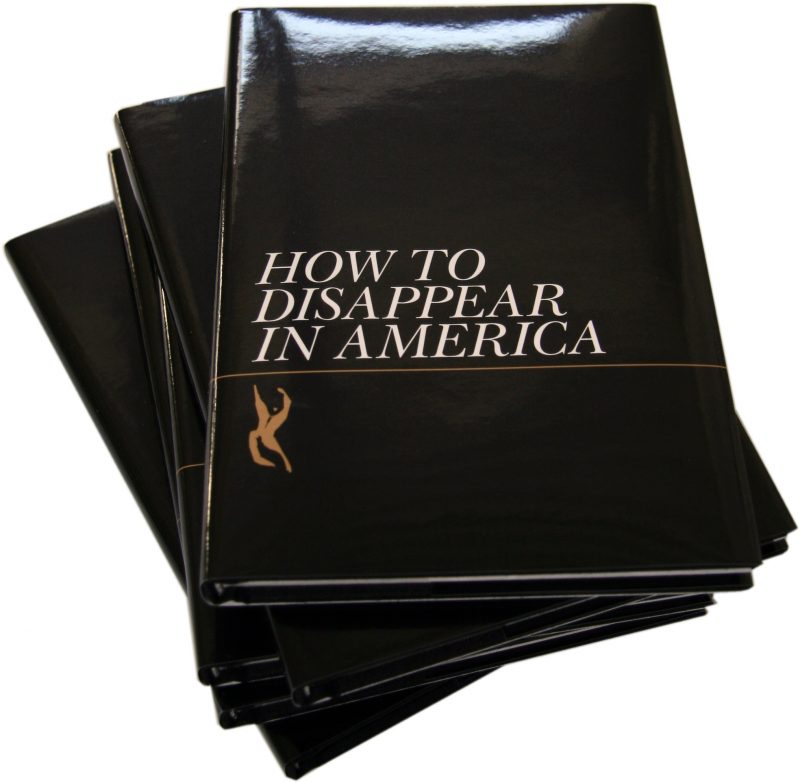

In December 2009, in the midtown studio of artist and Leopard Press cofounder Wade Guyton, a group of artists, artist assistants, curators, critics, and friends gathered to listen to the artist Seth Price read from his book How to Disappear in America. Except Seth Price didn’t, in the most literal terms, “write” the book—it’s an instructional guidebook compiled largely from various websites that provide tips for living off the grid, including how to torch a car, how to clear a campsite of human traces, where to sleep in the desert, how to kill a dog that’s trailing you, why gay bars are good places to hide out, and such insights as “If you have a helicopter looking for you, bury yourself in mud and leaves and you stand a chance of not being detected by your body heat.”

Price’s intervention transformed the original material, presenting not only the paradox of disappearance as the goal in a culture that aspires for the opposite (take, for example, the distinction between Price’s title and the now-defunct HBO series How to Make It in America), but also the bizarre authorless frontiers of the internet itself.

—Christopher Bollen

How to Disappear in America

THE BELIEVER: Did you pick the texts for How to Disappear in America arbitrarily, or were you cognizant of building some sort of narrative?

SETH PRICE: There was definitely a kind of urgency and high-stakes paranoia to a lot of the texts. That gives it a narrative sense. There was one text that was relatively down-to-earth that a skip tracer had written, like, “Look, I hunt people professionally, and I know all their mistakes. Here are my tips.” So you can trace some shifts in tone through the book. But I spliced them all together and took out the headings, cut things out, rearranged it, and wrote a kind of intro. And I had a free hand with dumb quips. There are a lot of places in the book where a paragraph ends with a stupid phrase like “’Nuff said,” or “Natch.” It was the salt on the dish.

BLVR: The book has been out for four or five years now. Have you received any interesting responses?

SP: A journalist wrote an article about the idea of “how to disappear.” It’s an old theme. There are television shows about it, plays, songs. Anyway, this journalist tracked down someone behind one of the texts I’d used in the book. Online, it was anonymous and unauthored, and said: “Anyone is free to use this, provided you don’t make money off it.” But when the guy who hosts the site heard about our book, he was upset, and got in touch with Leopard Press. They kind of smoothed it out. I think they explained that everyone involved had actually lost money on it! But I did see that later he was posting snide remarks about the artist Seth Price on some anarcho-utopian forum.

BLVR: Was he angry about the form in which his information was being distributed, or did he feel you were mocking his work?

SP: I don’t know. I think it was the idea that it was framed as an artwork. The category is suspicious. If we printed it up and just sold it in a left-wing bookstore it would have been a different story.

BLVR: Well, artwork is traditionally all about how to appear in America, not disappear.

SP: But artists can disappear into working. Being a successful artist encourages you to disappear into the forces of production and economy that were traditionally the enemy of some romantic conception of the artist’s life. You don’t work for the galleries or for the market. But you certainly can disappear into all that, and then you might as well be.

BLVR: You can become a brand name.

SP: For me, a big part of making work has to do with restlessness and boredom, which were very important when I was working day jobs. I was frustrated and desperate, which is a spur to thinking about artwork. You need that, and you need time to reflect. Once you have assistants to keep busy and galleries to feed, you can just vanish into it. But art’s not a job.

BLVR: That’s the whole problem with day jobs. You get paid by the hour, so you’re selling off your hours, one by one, to other people, for money. That’s frustrating if you want to do your own work.

SP: But on the other hand I think back to my job at EAI [Electronic Arts Intermix, a nonprofit media arts and distribution center]. I was given a computer and a lot of time to think about this new tool. I was working, but I was in this environment full of tools. Before that, I remember making paintings with all of the office supplies at this job I was working in Times Square. There are all these serendipitous tools around you, whereas the studio can become an echo chamber.

BLVR: Your work consistently plays off the idea of presence and absence. You make these polystyrene vacuum forms that hang like a canvas on the wall and present the contours of a physical object that actually isn’t there. Could we say that there is some refusal on your part to give yourself over to the object, preferring to be an artist who makes voids instead of concrete things?

SP: I would say, yes, I always had a problem with the icon, the image. I preferred working with text, and music, and video. The iconic image is done so well with painting and sculpture already. That may have led me to avoid a certain kind of image-making, and I ended up making these absences, but I was always interested in materiality.

BLVR: I recently re-read this essay you wrote in 2002, called “Dispersion,” which I have to say holds up pretty well ten years later, especially because it seems to suggest that the internet is a roundabout way of getting beyond the usual art-world market system. Do you think, ten years later, that the internet has fulfilled your fantasies?

SP: I don’t know. I started writing that essay not because of any interest in the internet, but out of frustration about how to be an artist, or whether I even should “be” one. Is it possible to make objects anymore? Is that interesting? So really it was my thinking through how to enter this other world, and when I finished it, I thought the text itself might be a piece.

BLVR: You initially wanted to work in film, didn’t you? You didn’t intend to make art objects.

SP: I was fighting it, because—well, I don’t know why. Maybe it was a self-destructive impulse. And the title of “artist” is just so embarrassing. Just to assert it: “I am an artist!” It took a long time to be able to say that. It started to seem coy to fight it, anyway.

BLVR: Finally, I wanted to ask you, what the hell happened to “internet art”? At the beginning of the twenty-first century, we were promised all of this internet art that was going to revolutionize the art world, or how we perceive it, and it’s really disappeared.

SP: It dissipated into a gas, and now it’s everywhere. I made a piece in 2000 called “Painting” Sites, a video that was based on internet searches for the term painting. I was simply taking the images that came back from that search. At the time it seemed new and exciting. I didn’t know of anyone else making art from internet searches. But then when I showed the piece I felt a sense of shame or embarrassment, because of the digital aspect. “Media art” felt so geeky. I remember artists I knew in college who ran away from computers, never got a cell phone, listened to music only on vinyl. That was what it meant to be an artist, not toying around with your computer.