It’s not much fun being a prophet. Sure, you get to speak truth to power, but inevitably you wind up getting popped in the kisser for your trouble. Then you go crazy and nobody listens anyway, until it’s too late. You’re essentially doomed.

Rock stars, on the other hand—not so doomed. Which is why I hate it when critics call Dylan and Springsteen and Marley prophets. Call them what they are: brilliant artists, intermittently courageous spokesmen, kings, judges, perhaps—not prophets. There’s only one modern musician who comes close to fulfilling the prophetic office, only one whose contract rider includes clauses such as “walk me around in a wooden yolk” or “saw my black ass in half.” His name is Gil Scott-Heron.

You needn’t take my word for it. Just listen to “B-Movie,” his 1981 paean to the Reagan Revolution:

What has happened is that in the last twenty years, America has changed from a producer to a consumer. And all consumers know that when the producer names the tune, the consumer has got to dance… The Arabs used to be the Third World. They have bought the Second World and put a firm down payment on the First one. Controlling your resources will control your world… The idea concerns the fact that this country wants nostalgia… Not to face now or tomorrow, but to face backwards.

Or consider “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” a song about the narcotic effects of screen addiction he released in 1971, back when you needed rabbit ears to get all three stations and Apple was still a record label. Scott-Heron was lamenting environmental desecration twenty-five years before the Kyoto Protocol. He decried apartheid during a time when most Americans had never heard of Johannesburg.

But it wasn’t particular issues that mattered to Scott-Heron. His music describes something larger: the way a great nation falls away from its moral precepts and into ruin, into a condition of spiritual malaise that has seen its apotheosis in the bigotry and psychotic greed of the Dumbya era.

If I’ve made the Book of Gil sound didactic, the fault is entirely mine, for it is the unique talent of the prophet to convert rage into poetry. Scott-Heron did so by creating a musical lexicon that ranged from Marvin Gaye to John Coltrane, from James Brown to Tito Puente. “Shut ’Em Down” may be a protest song about nuclear power plants, but it’s also a joyous hymn, complete with horn charts and gospel singers. “The Bottle” manages to turn the ravages of addiction into a house party with a raging Latin band. “Winter in America” is nothing less than the most gorgeous elegy ever written for this country’s conscience. Over a bed of somber keyboards, Scott-Heron sings of “robins perched in barren treetops” and cities that “stagger on the coastline / in a nation that just can’t stand much more.” It will sound odd, but his most obvious musical ancestor is Woody Guthrie, whose songs spoke to the disappointments of a land with so much natural wealth and so little mercy.

Scott-Heron is best known these days as an ancestor himself, a godfather of rap, the original uppity rhyming MC. But he has no more to do with some of the contemporary hip-hop stars who sample his tracks than Isaiah did with the idolaters of Judah. He preached—with a great and futile eloquence—against delusions of materialism and violence.

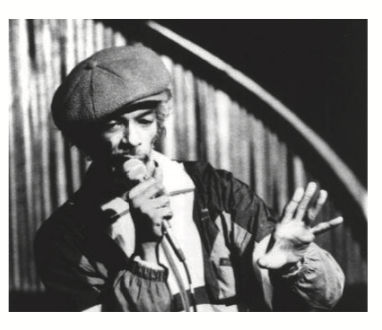

Like a good many of his Biblical brethren, Scott-Heron was gradually unhinged by his prophecy. The hypocrisy of this country, its easy hatreds and wasted potential, fueled his own self-destructive capacities. By the time I saw him perform, he was on the brink of prison time for drug possession. The years had battered his face. Time and again, he looked in sorrow at the snifter of cognac that trembled on his keyboard. And when he sang, his voice—once a magnificent, gravelly croon—sounded torn.