I.

The CAT 236D Skid Steer Loader is a muscular machine no larger than a compact Italian car. On a good day, with decent balance and a forklift, its arms—which shoot from the back like the tail of a yellow scorpion—can lift the equivalent of a full-grown American buffalo. Its diesel engine starts wheezing and whirring as soon as it’s turned on; it is operated by two levers from inside a single-occupancy cage. The 236 can spin on its own axis with a torque of 195 pounds per square foot, on four fat wheels that crunch and grind on gravel, while its hydraulic components pump, clutch, hiss, and twirl in a rumbling symphony of mechanical flow.

The loader can dance on rubble. But, like everything in life, instruments are only as good as their conductors. That is precisely why it was important for Jane Beckwith to find the right operator for the task. Someone she trusted, who was not only skillful but earnest. Able to feel in their bones the precision and tenderness that the job required.

A few years back, she had witnessed a man on his Bobcat single-handedly tearing down what was left after the Mercer Building fire, the ashen remains of an entire historical corner on Main Street. It all went up in flames one night, a total loss two blocks away from her museum, right next to Top’s City Café. In a 3,500-person town like Delta, Utah, where hardly anything happens, the blaze was all anyone talked about for weeks. Beckwith knew the father of the man who cleaned up the mess. She knew the man himself. He might have been one of her students before she retired, in 2009, from her job as a high school teacher. He certainly didn’t look like the type who would visit the Japanese internment camp exhibit. And she hadn’t seen him around recently. But that day he was kind, caring, and worked so gently, and with such diligence and respect for the burned history of their town, that after a few months she hired him to deal with Block 42 at Topaz.

That was a gnarly slice of a job. Yet once again, the man did what he’d promised, and left the plot neat and groomed. He even brought his little boys to sweep up the crumbling foundations of the mess hall, which was, as Beckwith put it, totally unnecessary.

Small-time riflemen, back-patio militias, and drunken hunters had always pestered this side of the desert, wilding out on dirt bikes and quadricycles, beaming their headlamps, and shooting at anything that could not fend for itself—maiming game, blasting bottles—and dashing back into the dust.

In 2002, the artist Ted Nagata, a former Topaz internee, had to redesign the camp’s memorial plaque after a Clint Eastwood wannabe riddled it with bullet holes. “We want one that doesn’t stand out in a crowd and ask to be shot at,” Nagata said then, laughing it off. But during COVID lockdown, things got out of hand. People went crazy. Shooting at tin cans and road signs didn’t do the trick anymore. Now they were stashing guns, ammo, and canned beef in basements. And if you paid attention at night, you could hear them blowing up boulders with Tannerite.

So when researcher Nancy Ukai found the map with directions to the stone in the National Archives, and, soon after, archaeologists Jeff Burton and Mary Farrell confirmed its location and published its exact coordinates on their open website, Beckwith finally made up her mind. The memorial had to be moved. And she knew just the guy to do it.

It is midafternoon in the August desert. We have been treading on dirt, leaping over bushes and rocks, hoping to reach the block where Arlene Tatsuno’s home once stood. Her birthplace.

“Where exactly was your bedroom?” I wonder aloud. Arlene smiles and defers in a whisper; a short shadow follows her as she walks: “You have to ask her.” And then, on cue, Jane Beckwith sinks her nose into a map she’s been waving in the wind and turns east to face an indiscernible spot in the scattered brush.

“I think you lived in Block 41, Barrack 6… but I could be wrong.”

The Central Utah Final Accountability Report will prove Beckwith right. But here, now, there’s only desert, fine dirt and greasewood baking under the dry beams of the sun.

Between 1942 and 1945, the view in every direction must have seemed infinite to a child. Wooden structures packed tight and stacked straight. A house of mirrors, a maze of undifferentiated continuity made of 504 identical pinewood, gable-roofed barracks perfectly aligned on a grid, walls covered in tar paper, and a snarl of mountains on the horizon.

The Japanese internment camp at Topaz was made of forty-two blocks, divided into four sections by two main avenues that met in an open plaza, all of it locked in by a perimeter of seven concrete guard towers. (A haunting imprint of the camp can still be seen on Google Earth, at coordinates 39°24’39″N and –112°46’24″W.) Below the barracks and the roads, underneath the alkali soil, hid a full prehistoric world. Topaz was set on the desiccated bed of Lake Bonneville, the largest continental body of water in the Pleistocene, an inland ocean brimming with sea creatures, whose layered fossilized shells would often bubble up in the mud after a strong summer storm. It was these shells that children like Arlene’s brother, Rod, busied themselves with during school breaks, bringing them to art class to turn them into toys, figurines, and the ghostly flowers that now overwhelm the vitrines of the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah.

From afar, Arlene; her husband, Gene, an ex-Navy Seal and a hunter, big as a polar bear; and Jane Beckwith, our guide and the founder and director of the Topaz Museum, look adrift in this openness. Topaz took a year to build, and just six months to become the fifth-largest town in the entire state of Utah at the time. It was also the second least populated of the ten Japanese internment camps during World War II. Today, we are alone here.

Hundreds of yards away, a four-foot-high barbed-wire fence stands against the wind. That is all that’s visibly left of the internment era, the only sign that a city built to imprison Americans with more than one-sixteenth Japanese blood did in fact exist in Utah.

Arlene tells me she was born in a room at the Topaz hospital, on the northern side of camp. This was, I later learned, an upgrade for her family: Rod had been born two years earlier in a stall at the Tanforan Racetrack, a temporary detention center set up by the government to hold displaced Japanese people in the Bay Area until Topaz was built. Arlene, they joke, is GI: government issue.

“It is over there.” Beckwith waves toward the north, map still in hand, pointing at a spot past a huge vertical rock where a gray pronghorn antelope has just bounded away over a patch of scattered debris and concrete platforms.

On our walk toward what’s left of the hospital, I follow Arlene’s sneakers as she steps gingerly on the dirt of her first home. She wears her gray hair long, tied back with a brown oval clip, and a pair of wolf earrings that kiss her neck; her black capri pants accent a frame that is both light and strong. Arlene is eighty but looks barely sixty and holds on to Gene’s hand like a girl at a matinee.

Between 200 and 250 Japanese and Japanese Americans lived in each block; the camp housed around eight thousand prisoners at any given time, Jane Beckwith explains, as she has for over thirty years, to visitors, to writers, and to the heirs of this story. Each barrack was divided into six rooms of different sizes, and families would take one, maybe two of the spaces, depending on the number of people and their needs. Every block had its own mess hall, latrine, showers, and laundry. Trees were transplanted from the edge of the desert and force-fed to grow. There were communal gardens, stores, churches, libraries, schools, and a post office, baseball teams and a baseball diamond, a theater and a dance company. During the three years when Topaz was open, some people passed away, some were killed, and others, like Arlene, were born.

Today you’d never know there used to be a town here, just by seeing the site from the road. As soon as World War II ended, the same government officials who put up the ten camps made sure that any trace of their existence was erased. They leveled the homes, uprooted the trees. Much has vanished in eighty years, but a lot more would have been lost had it not been for the museum Beckwith founded in 1983, Arlene tells me.

As we walk, Beckwith points at a gray storm cloud lingering over the mountains in the east. There, she says, you can still stumble upon the concrete pylons of the guard towers, iron rods rising from the ground like tulips, pipes and tin stove vents, and scraps of family lives twice uprooted: nails, crooked forks, glass shards, home-cobbled jewelry, and broken children’s toys made of prehistoric seashells.

It is hot, so every few minutes we pause to catch our breath. During one of these breaks, Beckwith peels her COVID mask off, and for the first time I see her bare face. Her green eyes are charged with sunlight, locked on a point beyond the horizon. Her skin is paper, and her mouth a thin line of ink. But a lump the size of a golf ball mars her right cheek. And when she sees me staring, she swiftly puts her sunglasses on. “It’s just inflammation, an allergy, nothing serious,” she says dismissively. Back in Delta, a docent at the Topaz Museum will tell me that it’s all the stress about the Wakasa feud.

Beckwith is in her mid-seventies. She is tall and assertive. Several times in the year that followed, I went back to my first question to her: Why she did it. Why did she unearth the Wakasa stone?

“People like this controversy, and I’m really sorry, because what I like is the museum,” she snapped at me one of those times. It was at the end of a long conversation, after a long, cold week.

That day at the Topaz site, however, she simply says it is all very complicated, that it has been horrible for her. People don’t understand. It would have been dangerous to leave the stone there in plain sight, where it could be vandalized. After all, it was Burton and Farrell who had published the coordinates of the memorial online, for anyone to see, in the middle of a brutal wave of Asian hate.

When we start heading back to our cars, I ask Beckwith where it is. If I can check the place out. “It’s over there.” She points to the west, at an area inaccessible by road. And it is clear to me now that somewhere in that direction is the spot where James Wakasa was shot dead in the spring of 1943; the place where a group of Issei, first-generation Japanese immigrants, emplaced a memorial stone in his honor; the place where they had to hide it, and from which, eighty years later, Beckwith would have it removed.

The sun is setting, and we still have eight hours of driving ahead of us, so we decide to keep going. “But I will come back,” I promise Beckwith, who now looks at me askance.

As we drive away, the smell of raindrops tapping on greasewood wafts in through the open window. I slow down to try to spot the place of the unburied memorial, but everything looks the same in the desert.

The storm finally catches up to us after we pass Delta, and by the time we reach the mountains, the landscape has split in two: to the left, the vertical gray of the rain sweeping over the valley; and to the right, a clean blue sky fluted on the horizon by the last traces of light beaming through the golden peaks of Utah.

On the stage of the Salt Lake Buddhist Temple, Nancy Ukai has started talking about her latest visit to Japan in search of information about James Wakasa’s past, and for the first ten minutes her words are dampened by the clinking of cutlery and voices coming from the kitchen. Ukai keeps her arms pressed tight to her body, like the wings of a small bird. Her green bomber jacket is patched with orange and lilac flowers. She holds the microphone close to her chin, alternately turning to the screen behind her, and the audience as she speaks about a sequence of photos. Her voice becomes reedy as she tells the audience that she visited Keio University, where Wakasa studied, but that there were no records of him there. She then went to Ishikawa Prefecture, where Wakasa was born. She was welcomed by local officials, who found no records of him there either. There were no records of Wakasa in the town registry or at the elementary school where he studied. No IDs, no report cards.

But then her team found Wakasa’s name in the manifest of a ship that sailed from Yokohama, Japan, to Australia in 1901. “He was a waiter,” she yelps, and suddenly there is only silence in the auditorium. “It turns out, if you work on a ship, you don’t need a passport,” she reveals. That one possibility, that James Wakasa had been a waiter on a ship, might explain the lack of physical records of him entering the United States.

Back in Delta, I had heard the name Nancy Ukai spoken in whispers. I knew she was the driving force behind the Wakasa Memorial Committee (WMC), which formed in 2021 in response to Beckwith’s unearthing of the Wakasa memorial, the last straw in what a part of the camp survivors’ community considered a long list of faux pas. That year, members of the WMC began waging a ruthless social-media war against Beckwith, a few of them intent on removing her from the helm of the Topaz Museum. The leadership of the WMC voiced its outrage and disapproval at raucous community meetings, rattling Beckwith’s nerves and causing her histamine lump. Ukai blamed her for dividing the Japanese American community. Others accused her of being self-serving, controlling, and, as a white woman, disconnected from the sensibilities of Japanese Americans and the cultural nuances of internment history.

The controversy around the stone was only the latest in almost a decade of tensions between Ukai and Beckwith. The two women started butting heads the day they met, in San Francisco in 2013, when Beckwith was campaigning for funds to produce the first narratives for the new Topaz Museum exhibits. Back then, Ukai told Beckwith that she wanted to help by reviewing those narratives. Over the coming months, Beckwith shared her texts with Ukai, who found them offensive, inaccurate, and heavily whitewashed. Without Beckwith knowing, Ukai contacted the exhibit’s founders, which put the museum’s opening in jeopardy.

In an interview with a Japanese newspaper, The Asahi Shimbun, Ukai credited the “curt description of the death of Wakasa” that Jane Beckwith wrote in 2013 as the affront that sent her on a quest to the National Archives in Washington, DC, to find the real story of the life and death of James Wakasa. Ironically, it also set in motion the chain of events that would lead to the excavation of the stone. At the National Archives in 2020, Ukai found the map drawn by George Shimamoto detailing the coordinates where the Wakasa monument had been buried in 1943. After Ukai published a photo of the map on her website, 50 Objects, Burton and Farrell drove from Manzanar, California, to Delta, to physically locate the memorial for the first time in eighty years. And they found it.

A few months later, between June and July 2021, they published in five installments a detailed account of their journey for Discover Nikkei. Their post included the Shimamoto map, a narrative with full details of the necessary corrections to the map’s coordinates that led to the exact place where the memorial remained buried, and four photos, including the surrounding of the burial site, and the visible top of the stone, which they marked on their GPS. Sixteen days after Burton and Farrell’s fifth installment, Beckwith unearthed the stone.

The gathering at the Buddhist temple is the latest development in a saga that has come to dominate Ukai’s life. For over a decade now, Ukai has been a fixture in the dialogue surrounding Topaz and Wakasa, but this was not always the case.

Born in Berkeley, California, Nancy Ukai graduated from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in 1976 with a double major in anthropology and East Asian studies. After college, she lived in Japan for fourteen years, and worked for Newsweek’s Tokyo bureau.

“She was an excellent reporter and researcher,” Frank Gibney told me in an email exchange. Gibney was Newsweek’s acting Tokyo bureau chief between June 1983 and January 1984.

In the ’90s, back in the United States, Ukai finished a master’s degree in education and published several academic articles on Japanese culture, education, and child-rearing. In the early 2000s she became the president of the board of trustees of the Princeton Public Library, in New Jersey, and in 2008, she completed a second master’s degree in media anthropology from the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

“She was one of the most creative people I know. She was intellectually curious about many, many things,” Leslie Burger, the former director of the library, said during a phone conversation. “She is cause-driven and has a ton of energy.”

Burger also described Ukai as an excellent fundraiser, who led at least three successful campaigns totaling over twenty million dollars.

“I don’t think she was involved with internment [activism] at the time, but if she was, she didn’t talk to me about it,” Burger remembered. “I think that back then her mother was ill, and her attention was focused on that.”

Fumiko, Ukai’s mother, a renowned jeweler and co-owner with her husband of a grocery store in the Bay Area, passed away in 2003, and it was around that time that Ukai left Princeton and the library, and she and her family relocated to California.

During our conversation, Ukai acknowledged that it was not until the summer of 2013 that she began to collect her family’s internment memories. She said that the more contentious aspects of her opposition to Beckwith date back to those days, and so does the disagreement over the narratives of the exhibit.

“The museum was basically Beckwith’s narrative, and it disregarded professionals, because there were no historians, and it disregarded community members, because they weren’t involved,” Ukai told me. “Now the truth must come out because this is part of a pattern. And the pattern is white ownership of our story, our artifacts, and their interpretation.”

One of the things that intrigued me most about Ukai was the reason for her late connection to Topaz history. Why had she avoided it for so long. Avoidance, I later learned, is rather common for internees and their descendants. In fact, there is a substantial bibliography that connects it to the trauma of Japanese Americans.

In the extensive list of papers about internment trauma, there is a compelling study published in 2019. The article is based on a survey of around four hundred Nisei, the US-born children of the Issei. Its authors—Donna Nagata, Jacqueline Kim, and Kaidi Wu—endeavored to find out if former internees talked about their experiences, and if they did, how much they said. The paper reveals that most of their subjects avoided talking about that time in their lives. And they had detached themselves from their recollections so much that those memories remained in their minds only as a form of posttraumatic stress.

“[More] than 12% [of Nisei] never spoke with their Issei parents about the camps,” the study reported, “50% spoke less than four times, and 70% of those who had any discussions conversed less than 15 minutes.” This social amnesia, paired with a sense of having been betrayed by their own country, fostered a feeling among camp survivors of equal parts resentment and guilt. “Rather than directing blame outward toward the government, many Japanese Americans tended toward self-blame: that they somehow should have been ‘more American,’” the authors concluded.

Amid all these erasures, Ukai told me, one memory kept sparking in her mind like a live wire. It was a vision of her mother sitting at the dinner table, driven mad by the mention of a man named James Wakasa. “They didn’t have to kill him. He was deaf!” Nancy remembered Fumiko screaming, her face red as an ember. Ukai credits that moment as her introduction to Topaz.

“My big regret is that I didn’t talk to [my mother] more, because she… it’s not that she didn’t want to remember. It’s just that we didn’t ask her.”

On July 27, 2021, Jane Beckwith woke up early, skipped breakfast, walked down to the garage, and dumped two long-handled shovels, a large cardboard box, and a thick blue blanket into the open bed of her 2001 Ford Ranger. The items lay loose near the plastic bucket she always carried to pick up random garbage—burger wrappers and sun-frayed McDonald’s soda cups—that ATV warriors scatter across the Topaz site.

It was warm, sunny, and still when she reached the southwest side of camp. A dust tail caught up with her as soon as she parked facing the F-350. Across the road, a gray Honda SUV sat empty, and a few feet back the CAT 236D Skid Steer Loader, just unloaded from the trailer, had started to growl from behind the barbed-wire fence. A DSLR video camera had been set up on a tripod to record the whole excavation. Other than Beckwith and three men—the forklift operator, a museum board member, and a delegate from the State Historic Preservation Office—no one was in sight.

The shadows were casting long and westward when the shoveling began. They first carved a perimeter on the ground, one foot removed from the burial site, leaving enough space to ensure that no damage would be caused to the stone during the dig. The soil, which the US Department of Agriculture classifies as strongly saline, poorly drained Abbott silty clay, was dry, very fine, and loosely set. The more they dug, the dustier it got, and past one foot deep, the contours they had edged around the stone started caving in and crumbling back against it.

Soon they had all pulled on their working gloves, gotten down on their knees, and begun to scoop out handfuls of dirt and tiny pebbles from the hole. It was almost like praying. A sense of calm assuaged Beckwith’s heart as she bent and dragged. She touched the stone with her right hand, but nobody who witnessed the scene would have said the gesture was remotely spiritual. A good Utahan, Beckwith was raised Mormon, but little if any of that faith was still left in her. In fact, her joy that day was earthy and simple, operational. Soil trickled through her fingers like cornmeal. They all laughed, and coughed, and talked as they toiled: maybe about the Pioneer Days Parade in Hinckley; maybe about children, or work, or money. It kept getting warmer, and the more they dug, the more they sweated.

When the area was half cleared, they stopped digging, stood up on the berm, and looked down into the hole. There, flat and heavy, was a gray boulder the size of a baby hippo, five feet long, three feet wide, and two feet tall. Underneath one edge there was enough space carved to slide in a yellow nylon ratchet strap. They didn’t want a chain to touch the stone, to scratch it or mark it in any way.

After tying up the boulder and binding the straps to the CAT’s forks, which now bridged the barbed-wire fence like a horse feeding on hay, the operator hopped into the cab and got the engine started. The machine whirled and rumbled. And suddenly its black mechanical arms rose, reaching up to the metal gods in the sky. The chain pulling the straps sang like a guitar string; it tugged and twanged; and the CAT tipped, bucked, and cranked, and for a few seconds, as it adjusted to the new burden, its back wheels hung clear in the air.

An audible gasp cut through the desert like a dart, and immediately the operator knew the load was teetering at the limit of what the CAT 236D could safely carry. Swiftly he put the rock back down and adjusted the CAT’s angle. And then the hissing of the pumps, and the pulling and the dragging, was all anyone could hear for a while.

Safely out of the hole, the stone was moved under the fence, eased flat onto a pallet, and lifted onto the back of the trailer. And when the midday light started to come down crisp from above, shining vertical on the boulder, Beckwith was finally at ease.

They drove out past noon, leaving behind an open ditch with a cluster of concrete and cobalt stone debris piled up neatly on one side. Among the remnants was a colorless shard of glass, and a piece from a bottle base embossed with a mark from the Hazel-Atlas Glass Company, which was established in 1902 and operated in Wheeling, West Virginia, until 1964.

Jane Beckwith led the caravan sixteen miles back to Delta. They were on their way to the museum, where this memorial, erected in love and buried in anger eighty years earlier, could finally rest. She could talk to Ukai tomorrow. It was after lunch. She was starting to get hungry, and she didn’t even remember what she’d had for breakfast.

It would be easy to argue that without the arrival of the Intermountain Power Plant in 1981, there wouldn’t be a Topaz Museum in Delta today. For nearly forty years, between the time when the Topaz relocation camp was razed and the coal plant appeared, Delta had remained a quiet, mostly agricultural town, subject to the whims of the desert and the Sevier River. Except for occasional family pilgrimages, there had been no concerted effort to remember what had taken place there during the war. In fact, by virtue of government design, most of that history had been erased, something the new power plant would soon change.

When the Intermountain Power Project was green-lighted, Delta woke up. Trucks started crisscrossing the town, their doors branded with the red, green, and blue logos of construction companies from Texas, California, and Sweden; corporate agents booked hotels, diners, and restaurants to full capacity; engineers, white- and blue-collar technicians, and workers from all corners of the world began moving in, and with them came their families. Main Street saw its first traffic light, and the modern housing projects for the newcomers in hard plastic helmets and utility boots inoculated the desert with a thriving international vibe.

“Delta High School changed immeasurably due to all that,” Jane Beckwith remembers. “Instead of ten kids in my class, I now had two sections of about thirty-six.”

In 1982, Beckwith was teaching a journalism course for high school seniors. And rather than making a yearbook, she decided, her students would undertake something different, more meaningful: a newspaper dedicated to understanding the Topaz internment camp, the stories that took place there, and how the camp had shaped the lives of Japanese Americans and Deltans. The project was important, national, exciting. Topaz was just fifteen miles west of town, so her students had the perfect opportunity to cover it in depth and embark on a discovery journey that could change their lives.

They named their newspaper the MoDel—for Model Delta—and started working on it right away. Beckwith filled the blackboard in chalk: there were leads, names, and phone numbers of the locals she knew who were connected to the Topaz camp. Her most promising senior, Wendy Lowery, who had a personal link to Topaz, would become MoDel’s editor in chief.

“When he came back from the war, my father worked at Topaz as a firefighter, and he and my mother lived out there for a little while,” Lowery told me during a conversation over Zoom. The house she grew up in, the one her father bought from the military when Topaz was taken down, was an officers’ barrack. “Even as a little kid, I knew what Topaz was.”

Lowery now has silver hair. She is stern yet soulful, and can be very funny but never laughs at her own jokes. Nor does she answer a question without first pausing to reflect.

The first time she met or spoke to a Japanese American internee in person was in 2022, the day she went into the Topaz Museum and saw the restored barracks. The doorknobs looked exactly like the ones in her childhood bedroom. (The construction was so bad, she remembered, that once, when she burped in the dining room, the windows rattled, and everyone in her family laughed.)

Occasionally, while reporting for the MoDel, a few of the kids would venture out into the desert around the Topaz site to conduct fieldwork, which might eventually turn into treasure hunting. If they found anything lying around and brought it back to Delta, they always let their teacher know. “Anything we picked up,” Lowery reasoned, “we would have shown to Jane, and she would have put it in a box.”

That box was how the Topaz Museum got started: organically, unintentionally. A trunk in Jane Beckwith’s home.

A few years after the class of 1983 graduated, Beckwith rented a small space at 45 West Main Street, inside the Great Basin Museum. For the next decade, in addition to teaching, she maintained and preserved what would be the first Topaz exhibit: a glass vitrine in the corner of one room. The first pieces on display included a twelve-inch-long white lace crochet doily, a pair of geta (Japanese wooden sandals), a chair, and some decorative household items. She started engaging with former internees and their families, who found out about the Topaz exhibit from waitstaff at their hotels or during dinner. As word spread, the visitors multiplied, and Delta became a pilgrimage destination.

“When people started coming to Delta, they would call me and say, ‘I’m here, would you like to meet?’ And we would chat and go out to visit the site together,” Beckwith recalled. “Some of the Issei started teaching me how to read this site, because it was difficult to know exactly what was out there without having somebody explain it to me.”

At the Great Basin exhibit, Beckwith soon had to make room for a wave of new donations, which arrived with the scores of visiting families and former internees who had rummaged through their attics for relics and mementos to bring to Delta.

But the internees were not the only ones adding to the collection. In 1991, a local Delta family donated a pinewood-and-tar-paper barrack, one of the original structures at Topaz, that they had lifted and relocated to town for use as a storage shed. The donation prompted the first gathering of an ad hoc Topaz Museum board, with Beckwith at the helm. Its mission: to restore the structure to how it looked in the 1940s, to fund the creation of a permanent museum, and to preserve the 640 acres of the Topaz site.

The main challenge for Beckwith and the Topaz Museum board was how to convey the range of emotions and memories resulting from a violent internment past; how to evoke not just the horrors but also the intertwined resistance through the lens of a museum exhibit.

There is a lineage of anthropologists who explore memory-building at the seam lines of conflict. In 2002, Lynn Meskell coined the term negative heritage to explain remembrance as the result of the cacophony of conflicting recollections and perspectives. Such a chorus of atonal tensions, Meskell believes, can be brought together around tangible everyday objects. In cases of local history, when there has been no formal effort to memorialize the past, whatever traces of material and place are left can become a node around which historical dissonance—with its conflicting claims of ownership, legitimacy, and authenticity—can reveal its multiple meanings.

After 1991, the museum board embarked on a journey to highlight these kinds of objects with even more fervor. There were fundraising efforts to purchase the land where the camp once stood, and to build a proper Topaz Museum: an eight-thousand-square-foot building in Delta that would memorialize and honor the survivors, while showcasing the way they were forced to live, what they did at Topaz, and the history of how they pulled through.

Life in camp was difficult. Temperatures ranged from below zero in the winter to above one hundred in the summer. Entire families who were removed from the Bay Area by train were driven in open trucks over the fifteen miles from Delta to Topaz. Men and boys in suits, women and girls in their Sunday best, caked in sweat by the sun and the bleakness of the desert dust. At Topaz, thousands of people struggled to adapt to life away from their homes, their farms, their schools, and the businesses the government had forced them to leave with a week’s notice. They left behind $200 million in property, 250,000 acres of farming land, and 20,000 cars.

There were long lines for bathrooms and dining halls (the only spaces with running water). The military shouted orders through loudspeakers. All prisoners had to follow the same ironclad routines and received the same pay depending on the activity: fourteen dollars a month for manual laborers, and nineteen dollars a month for professionals, including doctors. Internees worked at a pig farm, a chicken farm, a tofu factory, and a beet cannery, while sentinels posted in each of the seven towers pointed their barrels at them. The white potbellied stoves, one per room, could not keep the barracks interiors warm in the winter. And in the summer, even with the windows closed, nothing prevented the Sevier wind from blowing through the gaps in the walls, leaving a thick coat of dirt on everything: windowsills, linens, eyeglasses, faces. Apart from two sets of bunks, and the light of a single electric bulb, the barracks were empty, and smelled like dust, sun-heated tar paper, and burned wood. Each family was responsible for making their own furniture out of scrap lumber: tables and chairs, armoires, and benches were built in the desert, and most of those items were left behind when the camp was vacated.

It was also broadly acknowledged by survivors that the children’s experiences were significantly different from their parents’. Adults in the camp tacitly agreed to keep their anxieties to themselves and spare their kids. Rod Tatsuno remembers internment as mostly school, games, and fun. In fact, at Topaz, many of the Nisei made lifelong friends, and took music, theater, and art classes with some of the top Japanese American artists of the period. During their life in the desert, master landscape artist Chiura Obata and painter Miné Okubo offered twenty-three art workshops, including anatomy, flower arranging, and woodblock printing. A total of six hundred internees from ages five to sixty-five took these lessons.

“[In the mid-’90s] a friend of mine, his wife, and I went to visit Topaz because I had not been there since I was born,” Topaz survivor Hisashi “Bill” Sugaya says, speaking slowly into his webcam. He is in his eighties and wears a sleek black shirt and dark eyeglasses with a silver frame, the color of his hair. A breezy California accent sings in his voice.

“Jane showed us the campsite. There was not much at that time, just the small exhibit [that was] part of the Great Basin Museum.” An urban planner, Sugaya contacted Beckwith as soon as he returned to California. His friends worked for the American Farmland Trust and were eager to help broker a deal to buy the first 400 of the 640 acres where the camp had once stood. “That was my first involvement in the museum, and then Jane asked me to be on the board.” Sugaya has remained a board member ever since.

In those early years, Beckwith and the board had to learn how to write grants and deal with politicians, donors, and the state of Utah. On August 4, 2012, they broke ground at 55 West Main Street. The state-of-the-art, $2.3 million building would host an impressive collection: more than one thousand Topaz-made artifacts and their corresponding narratives, as well as over seventy charcoal drawings, and watercolor, ink wash, casein, and gouache paintings, all produced in Topaz between 1942 and 1945 by Miné Okubo and Chiura Obata, and other internee artists, including Hiroshima-born sumi-e painter Charles Erabu (Suiko) Mikami and self-taught oil painter Yajiro Okamoto. There would be woodcrafts, furniture, garments, jewelry, photographs on display, and even a projection room. The space would become a central place for camp survivors, their heirs, and Delta residents to gather, reflect, remember, and try to understand all that took place during the internment years.

“The fact that we have purchased all of the site—that’s incredible. It is incredible,” Jane Beckwith told me as if, while looking back, she was still trying to convince herself that the Topaz Museum was more than a dream.

The museum would have been an impressive accomplishment in a large metropolis like Salt Lake City, let alone in a small desert town like Delta. Its gray-and-black concrete polygonal building takes up a quarter block, and stands out like an alien starship amid the frayed Victorian architecture. The museum is partitioned into five cubic halls, and the main entryway features a wall of massive floor-to-ceiling windows, whose light gradually dims as one moves deeper into the space.

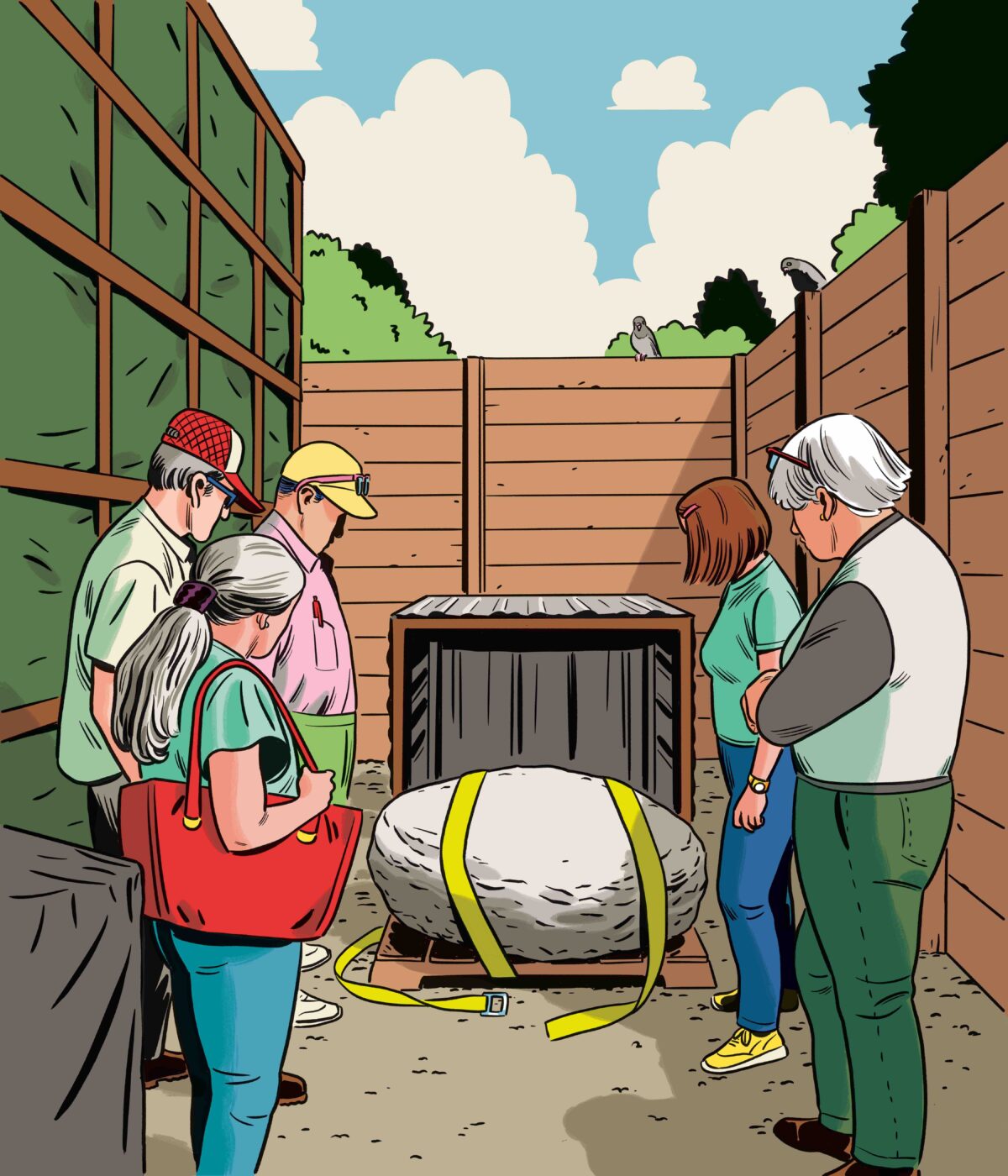

Past the permanent exhibit, on the back patio, near the rock garden and the restored barrack, is where, in August 2022, I first saw the unearthed Wakasa stone. Kept under a metal shed to protect it from the elements, it looked unnatural, still belted with the yellow nylon ratchet strap that was used to drag it out of its secret burial place.

“For that stone to become equal to all the work we have done…” Beckwith paused. “I’m really offended by that. I’m sad about that.”

I once asked Beckwith if she thought the controversy around the Wakasa memorial had undermined her legacy.

“My life’s work? That is not my life’s work!” Her dismissal was terse. What she did concede, however, was that forty years of work were now under what she believed to be unreasonable scrutiny.

But the reasons for all this attention were right there, in plain sight.

Months after our last talk, Beckwith sent me a copy of an email dated July 19, 2021, eight days before she dug out the stone. In the exchange, a group of Topaz descendants that included Nancy Ukai and the philanthropist Masako Takahashi discussed options for helping to pay for the unearthing of the monument before the end of the year. The looming possibility of the memorial being removed and taken who knows where, combined with the fact that its coordinates had now been published online, spurred Beckwith to action.

Only deeper inquiry would reveal all the anger her decisions unleashed.

II.

The two months that led up to the murder of James Hatsuaki Wakasa were riddled with tensions inside Topaz. On February 11, 1943, the Department of War rolled out a communiqué across the ten concentration camps on American soil, asking the internees three questions: Had they renounced their Japanese citizenship? Would they be willing to serve in combat on behalf of the United States? Would they give up their allegiance to the Japanese emperor?

Of course, most people in the camps resented the initiative. The Issei, barred from naturalizing because of their race, were now being prompted to give up their Japanese citizenship and become stateless. The Nisei had never sworn loyalty to the Japanese emperor to begin with, and signing the proclamation would have doubled as a coerced admission of guilt and a de facto military draft.

The “loyalty test,” as it was soon known, divided the internees, as factions within the camp disagreed on how, or whether, to respond to the government. “The ‘no-nos’ refused to sign it,” Arlene Tatsuno explained. “You had to say that you gave up any allegiance to Japan. That was like asking [you] to sign a document promising that you would quit beating your wife. ‘But I never beat her.’ ‘Well, but that’s beside the point.’”

A large group, however, believed it was best not to rock the boat. “They were the ‘yes-yes,’” Satsuki Ina, a psychotherapist, documentarian, and writer, explained. Ina was a baby during the internment years. “The [yes-yes] felt loyalty to the dominant authority, and of course, psychologically, this is like aligning with the perpetrator.”

The government’s strategy to balkanize the camps was laid bare in a recently declassified phone conversation between Lieutenant William Tracey, stationed in Topaz, and Colonel William Scobey, from the War Relocation Authority in DC. On February 15, 1943, Tracey told Scobey that by staggering the questionnaire vote block by block, he had successfully created a “machinery for registration” that would incite internees to coerce one another.

“If you get information against any man who is opposing your program and who is putting pressure on individuals,” Scobey responded, the government will brandish the Espionage Act against them.

“My father gave a short speech [to the other internees] when he learned that Japanese American soldiers were going to be drafted to do military service,” Ina remembered. “He made a five-sentence statement that said we should be treated as equal to the free people.” After that, Ina’s father was charged with sedition and imprisoned in Bismarck, North Dakota. A four-month-old baby in Camp Tule Lake, Ina was also designated an enemy alien by the US government.

In Topaz, debates around the questionnaire were carried on in poorly lit mess halls and at cold dining tables. Topaz Times, the internee-run newspaper, published letters arguing for and against compliance. Soon the discussions and the effects of the imprisonment took their toll and cleaved the community in half. Arguments broke out into physical violence.

Renowned artist Chiura Obata, at the time an art professor at the University of California at Berkeley and a yes-yes voter, was leaving the showers on April 4, 1943, when he was struck in the face with a lead pipe and almost lost an eye. Obata was taken to the Topaz hospital, where he remained for nineteen days before being transferred to Salt Lake City.

Alarmed by the violence, but ready to shield the government and avoid responsibility, Topaz director Charles Ernst addressed a letter to all camp residents:

I am writing to tell you personally that in the past sixty days there have occurred in Topaz incidents which have given the Administration grave concern. I refer to the cowardly attacks on Professor Obata and the Rev. Mr. Taro Goto and certain blackmailing and threatening letters. Undoubtedly, you also have heard of these and have been equally concerned.

Ernst made no mention of Wakasa’s death, which had occurred two months prior. The omission is telling: instead of creating divisiveness within the community, Wakasa’s killing had been catalyzing the internees into a robust resistance movement.

There is a distance of three circular dining tables—with five diners each—and three rows of chairs between Nancy Ukai and Jane Beckwith. Like her neighbors, Beckwith is sitting in front of a black plastic bento box overwhelmed with rice, shrimp, and different tempuras. Ukai is onstage, two cameras pointing at her. One is recording the event for the Topaz Museum; the other, for NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation), is set up by a wall with framed illustrations and photos. Earlier, the dining hall of the Salt Lake Buddhist Temple had functioned as a basketball court. Tonight, over two hundred people, including museum directors, state officials, religious leaders, and members of the National Park Service, are here to commemorate the eightieth anniversary of the killing of James Wakasa. The hoop by the stage has been lifted to the ceiling. The electronic scoreboard is off: Visitors: 00; Home: 00.

Beckwith looks at the stage, her eyes wide and unmoving, and watches Ukai take command of an audience that includes all the key stakeholders in the Wakasa controversy. From where I’m sitting, I recognize a few faces, people I’ve met in Delta. Kay Yatabe, a medical doctor and an expert on posttraumatic response, is here. Patricia Wakida, the new director of the Topaz Museum board, is here too. I don’t see Kimi Hill, Chiura Obata’s granddaughter and a big Beckwith supporter, and wonder if her absence is meant to send a message.

The mood is of a tense détente. Likely not a single member of this audience is unaware of the fact that Nancy Ukai found the map that led to the Wakasa stone—perhaps the most important archaeological discovery in Japanese American history—and that Jane Beckwith is the person who dug it up and moved it off-site. Everyone seems aware of the occasion, its solemnity, and the effort that has gone into it. For several months now, a group known informally as the Three by Three by Three—three people from the Topaz Museum board, three from the Wakasa Memorial Committee, and three mediators from the National Park Service—have been preparing for the event. Tonight there’s a healing ceremony taking place here at the temple; a second one will be held tomorrow in Topaz, at the exact spot where Wakasa was shot and killed. And at no time over the course of more than twenty-four hours will Beckwith or Ukai acknowledge, let alone talk to, each other.

A black-and-white painting by Chiura Obata, from his time at the Topaz hospital, shows the figure of a gaunt man doubled over, right leg stalling, arms projected forward and down, falling. He looks gutted. From the left of the frame, a small coyote-like dog with its ears pinned back runs up to him, the fear in its eyes rendered with two drops of ink. In the background is a wooden post from which sprout five straight lines of barbed wire. Behind, a few scattered bushes, the mountains, and a placid sky of slender horizontal clouds.

Obata’s painting, titled April 11th 1943, Hatsuki [sic] Wakasa, Shot by M.P., is based on collective accounts pieced together after Wakasa’s death. It is the only visual record of James Hatsuaki Wakasa being shot. No photos were ever found of the incident, and the only direct-witness account comes from the court-martial testimony of Gerald Boone Philpott, the nineteen-year-old private first class who killed Wakasa.

If the court-martial documents are to be trusted—and there’s good reason to doubt them—several guards had already seen Wakasa walking close to the fence that evening. A few minutes past 7 p.m., Wakasa had received a warning from Tower Post 9, ordering him to stay away from the perimeter, a directive he followed. But a half hour later, Philpott spotted him from Tower Post 8, again close to the barbed wire. Philpott claimed that Wakasa was walking along the fence, looking straight at him. The guard swore that he screamed at Wakasa four times, but the man kept going. When he was 250 feet from Philpott’s tower, Wakasa suddenly turned to his right and began climbing over the fence.

At 7:30 p.m., without aiming, from under his arm, Philpott took one shot at Wakasa with a Springfield 1903 thirty-caliber rifle. One shot, to just frighten the man and make him desist, he said. But the bullet hit Wakasa in the chest, piercing his heart and spine. Before the court martial, Philpott declared that he had never trained with that gun, and that it was his first time shooting it. He claimed he was not an expert marksman, and that it would have been very unlikely for him to be able to hit a target at such a distance, even if he had tried.

After the shot, Philpott says, he saw the man in the distance falling to his knees and then backward, three to four feet from the fence. There he remained, still, legs folded under his body.

When he heard the blast, Private Frank R. Baughman, the guard at Tower Post 9, telephoned Philpott. “Have you got in any trouble there?” he asked. Philpott told him what had just happened. Neither of them abandoned their positions as they waited for the medic to arrive. During the trial, Baughman said he saw a little dog circling the body.

The coroner’s statement in the court-martial files details Wakasa’s outfit that evening: two layers of trousers, a blue pair underneath a brown pair; instead of underwear, an armless homemade knit sweater, his legs passing through the armholes; thick cotton socks; oxford slippers; a brownish-tan sweater; and a dark blue mackinaw coat (likely one of the Philadelphia-made Buzz Ricksons the army supplied to all the internees). Sewn into the undergarments was a money belt with sixty-five dollars. The inference is that Wakasa was dressed to escape. Temperatures that day reached a high of fifty-seven and a low of thirty-three.

It took forty-five minutes for Lieutenant Henry Miller, commanding officer of the military police, the force to which Philpott was attached, to give notice of Wakasa’s death to camp authorities and Tsune Baba, chair of the Topaz Community Council. Those forty-five minutes of blank record call for uncertainty and speculation.

Few of these details were known to the internees. Years later, some recalled hearing the shot; others remembered the military ambulance driving along the perimeter of camp. Military police were not authorized to enter Topaz, so to reach Wakasa’s body, they would have had to jump over the barbed wire and pull his body under the fence.

For most of the internees, Wakasa’s death remained a mystery. In many ways, eighty years later it still is. Court-martial documents state only that Wakasa was unintentionally killed by a nineteen-year-old private, shot at the same distance from which hunters shoot down antelope.

It happened at twilight, on a bright evening with good visibility and a mild westerly wind.

By most accounts, Wakasa was a well-educated and affable man. He had a habit of walking his dog along the same route every evening. He lived in Block 36, Barrack 7, Unit D. The reports state that he had a full head of white-gray hair and mild Japanese features.

The morning after Wakasa’s death, a group of three social workers and two neighbors, led by Eiichi Sato, gathered at the murder scene to complete a report of the incident. As they approached the southwest fence, thirty-five feet from the site, a military Jeep came speeding toward them from the North Road and stopped abruptly. The driver stood on the seat and turned to them as he grabbed a submachine gun from his companion’s hands. Pointing at Sato, he yelled: “Scatter or you’ll get the same thing as the other guy got.”

“We ate with [Wakasa] in our mess hall and used the common lavatory and the common facilities,” read a letter that camp survivor Toru Saito sent to Nichi Bei News, a Bay Area newspaper, on September 2, 2021. “I was there when he was murdered by [a] US Army guard, April 11th, 1943. The actual spot of his death was kept unknown from us all these almost eighty years.… My dear mother died at age 106 in 2012, still worried [about] his remains…. Now 78 years later, the strong feelings of shame, guilt, and resentment return as I write this letter.”

In the days that followed Wakasa’s death, the eight thousand Japanese American prisoners at the Topaz internment camp stopped all activity at the furniture factory and the adobe brick unit, the bean sprout center, the milk plant, the warehouse, and the motor pool. The general mood was somber. The military entered a phase of red alert, and police started carrying gas masks and Thompson submachine guns at all times. Rifles that had once stood guard against the desert night suddenly were pointed into the camp.

Some of the internees clutched clubs and bats as they walked between the kitchen and the hospital, between the showers and the residence halls—anything to fend off the guards. Children stopped playing outside. There were feverish meetings behind closed doors, and tense discussions among the internees; the military and the camp authorities were not forthcoming with their investigations. Silence, suspicion, and mistrust prevailed, and a state of physical tension strained the air for days. It wasn’t until the War Relocation Authority called off the alarm on April 13 that some level of normalcy was regained at Topaz. Two days after Wakasa’s murder, the authorities announced that the sentry responsible for the shooting had been arrested and would be court-martialed at Fort Douglas in Salt Lake City.

There are a few photos of Wakasa’s funeral housed at the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. A couple of them show the casket, fitted with wreaths, crosses, and a heart made of paper roses and lilies, equal to or even more beautiful than natural ones.

In the illustrated memoir Citizen 13660, a classic of Japanese American literature, the artist and Topaz internee Miné Okubo dedicates two drawings to Wakasa: one is of his funeral, and shows people in grief, fat tears rolling down their cheeks; the other features a group of eight women in patterned dresses, gathered around a table, folding paper flowers.

The wake took place on the afternoon of Monday, April 19, a week after Wakasa’s death. It was held on the Topaz school grounds, at the open square in front of the basketball hoops of Block 32. Camp authorities had denied the Issei’s request to hold the service at the scene of the shooting. The administration had also refused to declare a general holiday that day, but all the schools stayed closed, and most adults skipped work.

The sun was shining bright when people started assembling in front of the stage. By 2 p.m. it was clear there wouldn’t be enough seats for all the mourners, who numbered close to two thousand. Groups of children wriggled around in skirts and suit pants, under or out of their parents’ sight, plunged into the throng, leaning on chairs, on their tippy-toes, hiding by the piano or the speakers.

The casket was brought up to the stage by six pallbearers. Everyone rose, and the ceremony was conducted entirely in Japanese, except for a condolence letter read by the chief of the Welfare Division, and a brief speech by one of the camp administrators. “Rock of Ages” and other hymns and prayers were sung in Japanese. There were a vocal solo and paper flower offerings. By 4 p.m., when the funeral ended, streams of clouds had gathered above, and a strong wind rustled and shook the paper flowers.

The pallbearers carried the casket to a hearse amid the growing gale. Plumes of desert dust began swirling along the streets, over the barracks, and away into the valley. The hearse moved down the main avenue, past the entrance gate, and disappeared into the wind. Later that day, Wakasa’s remains were taken to Ogden, Utah, to be cremated.

It was the biggest funeral ever held in Millard County, possibly the largest Japanese American funeral ever held in Utah, and the largest in the entire United States during the wartime era.

A report on the Wakasa incident describes a continual feeling of suspense after the service among the military personnel, who kept wondering what the attitude of the internees might be on Tuesday morning. But as the hours passed, their fears slowly dissipated, the crews went back to their posts to pick up their tools, and camp restarted its normal rhythm once again.

That could have been it. Ceremonies and a court martial. The camps would be dismantled a few years later, marking the return of the Japanese American prisoners to some semblance of freedom.

It could all have ended there. But then there was the stone.

A crew of six men, some wearing black caps, others straw hats, work in the foothills of the Topaz mountains. Four of them push and roll a big boulder with long wooden poles. Two wait on the bed of a truck with the number 42 painted on the driver’s door, ready to assist in lifting the rock. They all stand near what looks like a wooden pyramid, an aid in the shoving and the heaving, in keeping with the traditional Japanese way of stone gardening, which involves levers, pulleys, and ropes.

Chiura Obata’s drawings again provide a good visual reference for understanding how internees sourced materials in the desert to bring them to camp. “The War Relocation Authority offers six trucks every Sunday in which 150 evacuees can go on a picnic,” Obata wrote in his diary, a text reproduced by one of his granddaughters, Kimi Hill, in her book Topaz Moon: Chiura Obata’s Art of the Internment. “Collecting unusual trees, bonsai-like greasewood, unusual stones and topaz gives relief from the meaningless barracks life.”

Most of Obata’s rock-gardening works are still unpublished, but Hill agreed to share some copies with me.

“There is a quarry, which I think is about ten miles west of the camp,” Nancy Ukai mentioned during our conversation. “It’s called Smelter Knolls. I’ve never been there, although I’d like to go the next time I’m in Utah. There are sketches of it by Chiura Obata… So the assumption is that the stone came from there.”

In two black-and-white ink-on-paper drawings, Obata illustrates what seems to have been the way the Wakasa stone was sourced and brought to camp. And while the how is clear, what remains a mystery is when exactly the monument was emplaced.

Military records show that by mid-May of 1943, an agricultural crew had set up a structure of rocks and concrete on the exact location of Wakasa’s death. The memorial was built in defiance of the War Relocation Authority, which had labeled Wakasa’s death as an escape attempt. On her website 50 Objects, Nancy Ukai explains that the monument was constructed using “a sack and a half of stolen government cement to which they added native rocks.” It was likely erected without ceremony, under the cover of a thick desert night, sometime between mid-April and early May of 1943.

Topaz authorities ignored the monument at first, but in a letter dated June 8, 1943, John McCloy, assistant secretary of war and a fierce proponent of Japanese segregation, asked Dillon S. Myer, director of the War Relocation Authority, to make sure the Wakasa memorial was removed: “I can see a real objection to any action which permits monuments of this character to be erected. Wakasa’s death arose as a result of justifiable military action and it seems most inappropriate that a monument be erected to him.”

Soon after the exchange, Topaz director Charles Ernst assured Myer that the memorial had been destroyed and forgotten and there would be no record of the stone: “[Everything is] torn down,” Ernst wrote, “and the rocks which were used in its construction… completely removed from sight.”

For many of the internees, that was the end of the Wakasa saga. The erasure would be repeated two years later with the razing of all ten internment camps. In a sense, Arlene Tatsuno told me, the physical leveling of Topaz was a clearing of the slate. Life had to go on.

But memories have a way of coming back. In July of 2021, the Wakasa memorial, supposedly torn down eighty years prior, awakened from its desert slumber. In a final act of defiance, instead of destroying the memorial, the Issei had buried it, leaving behind a simple diagram with its coordinates. The map, drawn by an internee named George Shimamoto, made its way to the National Archives in DC, where Nancy Ukai found it.

I tried to talk to Ukai about her discovery, but in April 2023, right after I saw her at the ceremony for the eightieth anniversary of Wakasa’s death, she stopped communicating with me. One thing, however, was clear the last time we spoke: coming across that map had made her tingle with excitement. She was grateful for the physical discovery of the memorial stone, for Burton and Farrell.

Little if anything could have prepared her for what came next: Beckwith, a white woman, getting there first, unburying the monument, and taking it to a museum. The Issei’s hands were the last to touch the Wakasa stone before it disappeared for almost a century. Beckwith’s hands were the first to touch it again, after all that time.

After a left turn on Route 6, the reality of Delta starts to sink in again: dry brush on both sides of the road; the town of Lynndyl, the hundred-car freight trains; high-voltage towers lined up, each in a wide stance, gripping power cables that crackle for miles along the expanse of the Utah flats.

We’ve been on the road for nearly ten hours and still have one more to go. It’s my turn to lead the three-car convoy of raucous middle-aged Japanese women—artists, curators, doctors, writers. Kay Yatabe is riding shotgun as I drive. Kimi Hill is in the seat behind me. After a year of talks and meetings, we became friendly, and they invited me to join them as they hopscotched around the Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument, ahead of a private ceremony at the Topaz site later this evening. Organized by Hill, the event will honor her grandfather’s most famous painting, Moonlight Over Topaz, with a koto performance by two young Deltans.

Our banter has been going strong since early this morning, but as the light starts to dim, we all grow quiet, and I begin to retrace my own path here. Along this same road two years back, my wife and I were on our way from New York to Santa Cruz, California, when we detoured through Delta. We were struck by the Topaz Museum’s sleek modern building and doubled back to yank on its door, but it was closed for COVID. A year later, we swung by again. This time the doors were open, and, by sheer chance, Arlene Tatsuno was visiting from the Bay Area. We sat next to her and her husband, Gene, in the otherwise-empty projection room, unaware that the documentary footage on the screen was her father’s own film Topaz. As the credits rolled behind her, Tatsuno grabbed me and said: “Have you met Jane? She’s responsible for all this,” and took me by the arm to meet Beckwith, whose face was already showing the first bouts of histamine.

I knew immediately that the Wakasa controversy was an important story for me to write, even though at the time I didn’t understand why. I had little knowledge of the Japanese American internment experience in the United States. My beat, if I could call it that, had been Indigenous struggles in Latin America.

It took two years of writing a story about others’ memories before I stumbled into my own. Born in Argentina in the 1970s, I witnessed, way too young, a country that turned on its own citizens, and experienced, personally and intimately, the ensuing struggle for collective memory that continues to haunt Argentine families and friends today.

For almost eight years, between 1976 and 1983, the Argentine military, supported by the United States government and its blind eye to human rights, kidnapped, tortured, and disappeared thousands of people without trial, without reason, in systematic acts of terror focused on instilling fear and obedience, in order to make Argentines acquiesce to the neoliberal free market policies of the Washington Consensus. After the dictatorship ended, the military forged a plan of oblivion to evade the consequences of its actions. It tried to take charge of the narrative by lying, hiding records, and altering the architecture of entire places.

One of the plaques in the sun-drenched lobby of the Officers’ Quarters of the Escuela Superior de Mecánica de la Armada (ESMA)—the infamous Navy School of Mechanics, a former clandestine detention, torture, and extermination center run by the Argentine Navy—describes an example of this type of forced architectural amnesia:

Since the IACHR [Inter-American Commission of Human Rights] inspection was agreed, the Argentine dictatorship implemented various strategies to hide the extent of its crimes. It carried out political propaganda campaigns and modified the buildings that had functioned as clandestine centers so they would not match the descriptions by former detainees. ESMA Task Group 3.3 made profound changes still in place today.

Only through the memories of survivors can we know the history of that place and what happened inside it. Remembering is a willful act. But so is forgetting.

The ESMA campus is parklike, with cypress, cedar, and ash trees lining alleyways between grand old buildings; the only architectural evidence of its more recent use as a detention center are the fifteen guard towers studding its perimeter, all retrofitted in concrete and installed just months before the military coup, and in clear anticipation of it. The place was turned into the ESMA Museum and Site of Memory in 2015 by then president Néstor Kirchner and contains harrowing and meticulously displayed evidence of the horrors endured by its detainees, including the army helicopter that regularly dropped torture victims, still alive, into the nearby Rio de la Plata.

I went to the site with my brother, but at the last minute he decided to wait in a café during the two hours it took me to walk it. I understood why he would not want to put himself through the tour.

On September 19, 2023, when I landed back in New York, my phone notified me that the ESMA had been placed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Someone is hungry in one of the other cars, so Kimi suggests we stop at the metallic red sign of a gas station that is also a hoagie restaurant. I fill up the tank while the others stretch their legs and talk about what to eat. Three blond kids drive up in a black truck. They have a yellow dog, maybe a Lab, and can’t stop staring at our group. Perhaps they’ve never seen so many Japanese people all at once. This may be what Deltans felt about Topaz in the 1940s. All those highly educated, successful Japanese Americans showing up out of nowhere.

The kids linger for a while, take their dog to pee on the side of a rusted tanker truck, and snatch a last glance at us before screeching away into

the hills.

Racial trauma can start healing only once its social precursors resurface, turn visible, and are acknowledged. Direct acceptance, an admission of guilt on the part of those who caused that pain, is an invaluable part of the process. During the redress movement in the 1980s, conditions were ripe for former internees to start healing. When the US government finally admitted its wrongdoings, and recognized that its internment policies had been shaped by “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership,” the internees received the first official acknowledgment of their mistreatment and a confirmation that their pain had been real. Until then, however, most Issei and Nisei had had to suffer their experiences in silence.

This liminal mental space was the context in which the Topaz Issei and Nisei began interacting with Jane Beckwith in the 1980s. Before the US government fully acknowledged any wrongdoing, Beckwith and the people of Delta set in motion a process of communal redress, the first step on a path that would allow many of the incarceration victims to feel heard and start healing on their own terms. The Topaz Museum materialized as a pivotal interlocutor, an early countersign that validated the voices of those who had suffered but could not yet express it in their own words. In its role as an ally, the museum helped preserve and document painful reminders of the incarceration, its racist origins, and the hardships that both the US government and American society imposed on people of Japanese descent—Americans and legal residents alike. The museum institutionalized these memories and gave them a physical form and place.

Rarely does trauma literature from the Global North, a constant aggressor, consider that it should be the victim, and never the perpetrator, who determines the direction and pace of recovery from racial pain. Following the government’s admission of guilt, it was up to the Japanese American community to express its restorative requirements—demands that ranged from retributive justice to plain forgiveness. It is at that point that the negotiation between victims and perpetrators sets the bar for a new social contract.

But while the Topaz Museum was a first step toward that broader social acknowledgment, the unearthing of the Wakasa stone felt like a step backward, a new betrayal.

There is no denying that the Topaz Museum, and a large portion of Beckwith’s actions, exist in a nexus of cultural, political, and racial tensions in America that are now reaching a boiling point. Most of the Issei and the Nisei trusted Beckwith to be their ally in Topaz. Early on, Topaz internees Rick Okabe, Ted Nagata, Bill Sugaya, Chuck Kubokawa, Grace Oshita, and Dave Tatsuno confirmed Beckwith at the helm of the museum board, an entity they had created. No one today should doubt they had good reasons for doing so. Beckwith was their Topaz connection, the manager of an operation set up to help expose governmental responsibility and elicit an admission of guilt. And she was white. In the context of those early days, it would have been difficult for the victims of incarceration to set up the Topaz Museum from afar. Beckwith wasn’t perfect; she wasn’t supposed to be. She was there, and she was just the ally they needed.

Allies—especially those who witness, if not directly condone, the crime against which they later seek redress—carry their own guilt and resentment. I wonder if unearthing the stone was Jane Beckwith’s role all along. Could she have done anything other than what she did?

It doesn’t take long for Kimi Hill and the others to come out of the restaurant, gnawing on their sandwiches. Kay Yatabe hands me a brown caramel lollipop, which I save for later. Jane Beckwith is eating a banana under the restaurant awning. Her stress allergy has made her cheeks swell again. We haven’t talked much this afternoon, but I see the uneasiness in her eyes. She tells Hill that it is getting late, and she needs to go back to Delta to get ready for the ceremony. She turns her Ford Ranger around and dashes back into the Sevier Desert, that antediluvian, fossilized ocean.

When I pictured the Topaz Museum in the months and years after my first encounter with Beckwith, I rarely thought of the unburied memorial as one of its defining characters. Nor did I think of Beckwith, or the barracks, or the internment. Instead, what kept coming to mind was a small doll: a Minnie Mouse figurine—just a few inches tall, made of shells and black wire, held inside a glass display—that I’d noticed as I walked out of the main exhibit room that day. The doll had two black-painted seashells for ears and five red-painted snail shells for a hair ribbon. For a face, half-moon black-and-white eyes and a pointy nose were etched onto the tip of a seashell. The Minnie Mouse was connected by a piece of cotton thread to a paper tag with the name Misao Kanzaki handwritten on it.

When I searched the Utah State University Digital History Collections recently, the name Kanzaki pointed to the record of the stillborn child of Ray Toshio and Mrs. Kanzaki. The birth took place on May 14, 1944, in Topaz. Misao was a boy. I don’t know if the doll was meant for him.

A few items are waiting for us in Beckwith’s garage. Eight metal folding chairs leaning against the wall and a stack of plastic patio recliners. We shove them into the back of the car, and head to Topaz for the ceremony.

The dispute over the stone remains at a standstill. It has been months since I’ve heard from Ukai. I wonder what a path forward might look like. History always finds its way into the future, as does memory to preserve it. But who will remember this fight a decade from now. Will it still hold any meaning?

The landscape outside Delta is punctuated by dairy farms. Around 6 p.m. it’s dinnertime for cows, and we see them lining up by the side of the road, their heads pushing through red fenceline bars, muzzles shoved into the feeders. At times, the smell of methane fills the car. We cross the small bridge over the Sevier River, a thread of water wiggling in a sea of dust, and we see the crown of the moon rising from behind the powder-red ridge of the mountains. The road becomes emptier, hemmed now by small houses, many of which are converted barracks that the government sold to locals after razing Topaz.

There are three SUVs already parked at the entrance to the site when we arrive, and a dozen people milling around in groups, casually walking between five or six commemorative plaques, their shadows spilling out onto the gravel. I assume they’re locals who have shown up for the ceremony, but as soon as they see us, they retreat to their cars and drive off.

By the time we enter the square mile of camp, the moon is already parked over the mountains. We drag the chairs from the back of Beckwith’s truck and arrange them in a line facing east, on the concrete platform of a leveled mess hall. Some of the women grab a seat, others walk around taking photos. Except for a lone cricket, the desert is all silence.

Suddenly a black truck rushes toward us from the horizon, high beams on, leaving in its wake a tail of dust. When it pulls up beside us, two blond kids barely out of college jump out and start unloading instruments. Bessie is wearing a purple coat because, she explains, it’s going to get cold. “The desert changes the pitch of the strings,” the other girl, her sister Stephanie, says to no one, as Bessie brings out a few hand drums and a violin, which they carefully set on a chair. Their chatter is lively, rhythmic, and slightly mesmerizing. Finally, Bessie pulls out the koto, a six-by-one-foot zither, Japan’s national instrument. She handles it carefully, setting it on two black wooden trestles just as her teacher, Shirley Muramoto has taught her.

“It’s like poetry when she plays it,” Stephanie gushes. Muramoto learned the instrument as a toddler, sitting on her mother’s lap at the kitchen table. Her mother had first played the koto “at camp.” “Quite a progressive summer camp it must have been,” Muramoto had thought for years. It wasn’t until her later teens that she found out about relocation, Japanese American internment history, and Topaz, where her mother had been an internee.

No live music has echoed here since the camp closed, Kimi Hill tells me. Almost eighty years later, two Delta girls are about to play a traditional Japanese instrument they’ve just started learning during lockdown from the daughter of a Japanese American internee.

They will start with “Kojo no tsuki,” “The Moon Over the Ruined Castle,” Stephanie announces. She plucks one string at a time, first with her thumb and then with her index and middle fingers, as her sister accompanies her on the violin with long notes that drip like fog under the main melody.

I’ve heard this tune before. It suggests at an upright piano in a smoky bar; a saxophone in an ’80s movie. It was, I believed, a Thelonious Monk tune. But back home I learned that, although Monk recorded it and played it often, the original had been written in 1901 by Japanese composer Rentarō Taki as a lesson for piano. Printed and reprinted in Japanese high school music books for over a century, it was as popular in Japan as jazz standards are in the States.

The sisters play it tentatively, but the magic still vibrates in each note. As I listen, I think about memory, who holds it, and who carries it forward. Taki and Monk, and now these Delta sisters.

We all sit quietly, and when the girls are done, we cheer and laugh. Stephanie asks the audience if any of us has ever played the koto. Nobody has. So she invites us to try. She’s been so smitten with the instrument that she recently bought a smaller one, which was shipped from Japan. She painted a white crane on it with a red sun behind. Stephanie doesn’t know what these symbols mean, but she copied them from drawings she found online, and it looks very pretty.

It is late, and cold, so we all huddle under blankets.

The moon now hangs like a round fluorescent globe over the desert and the mountains, and there is nothing we can do to stop it.

*

This story was supported in part by the Literary Journalism program at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, in Alberta, Canada.

*

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the name of Nancy Ukai’s mother. It was Fumiko, not Umiko.