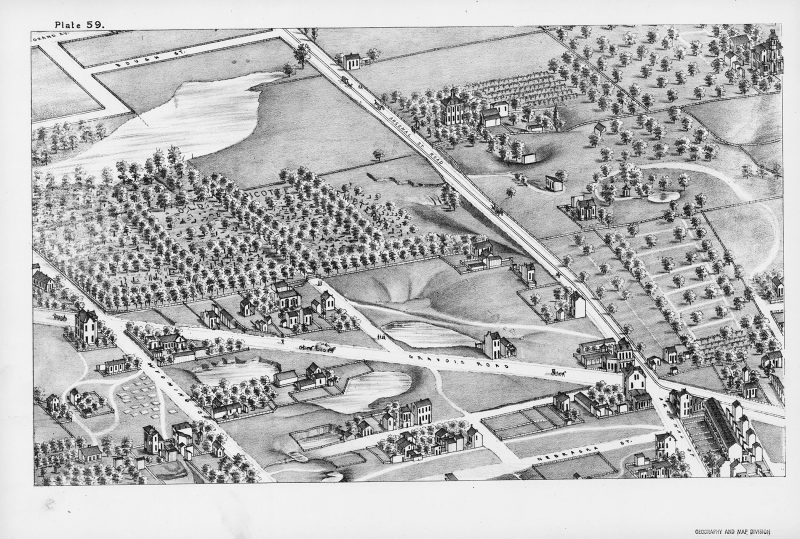

Near the intersection of two rural thoroughfares—each broad road dotted with horse-drawn hay carts and carriages the size of dimes—stands a wide cemetery of a few dozen graves. Rows of leafy trees project slats of shade over the tombstones, some shaped as simple blocks and others bearing upright crosses. A broad pond sits just north of the cemetery grounds, glimmering dully gray and black within the surrounding pastoral landscape. Almost too small to see, at the cemetery’s arched entrance gate stand two figures, a formally dressed couple approaching the graves. About fifty yards behind them on the path, a family of four makes its way toward the cemetery in a miniature phalanx. The husband wears a hat and coat, his wife wears a dark short-brimmed hat and a black dress that trails in the dirt behind her. Their two children walk between them, a possibly teenage boy nearly the height of his father, and a toddler clutching the mother’s hand. A colossal piece of text, each letter the size of one of the nearby houses, hovers like a low mist above the scene. The people making their way toward the cemetery are oblivious to the floating message, which reads old picotte cemetery. Chances are they know it by a different name: the same plot was variously called Old Picker’s Cemetery, Piggott, Vickert, and Riddle. Prior to these, in 1845 it was officially known as Holy Ghost Evangelical and Reformed Cemetery. Many victims of the city’s devastating cholera epidemic of 1849, which killed nearly 10 percent of the local population, were buried there.

Like plots in a graveyard, sites on a map are the eternal resting places for the once-bustling activity of human life: here lies the halted movement of history. Though the visitors to this cemetery are presumably fictitious mourners—one cartographer’s set of emotional placeholders, akin to the artificial pedestrians of an architectural model—the bodies in the graves, though unnamed, must be actual characters from the city’s narrative.

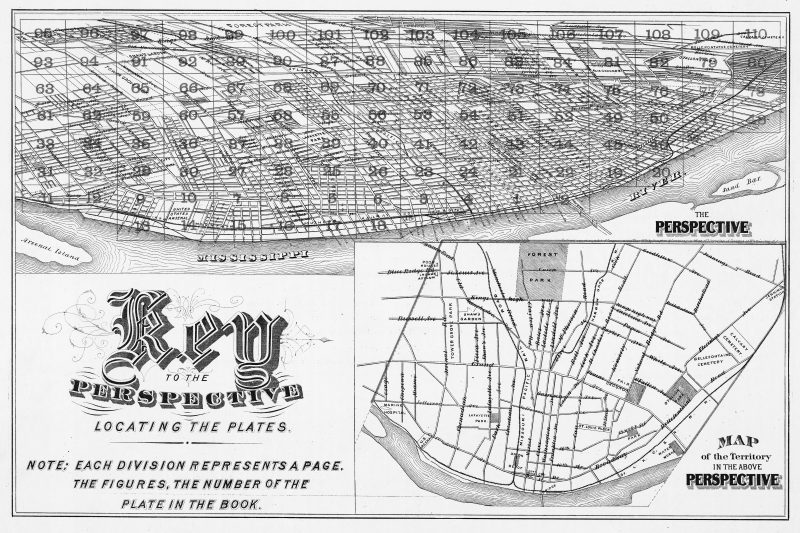

These immobile acres of life, from the turn of the twentieth century in St. Louis, Missouri, represent only a fragment of the immense panoramic map called Pictorial St. Louis, Metropolis of the Mississippi Valley: A Topographical Survey Drawn in Perspective A.D. 1875. Charted by the nomadic draftsman Camille Dry, the map is widely considered the pinnacle of the form, and one of the more impressive feats of mapmaking in the modern era. Cartographic historians have called it “the most ambitious of all American city views” and “the Sistine Chapel of panoramic maps.” As the largest such map ever produced, Dry’s project remains staggering in its size: if each of the 110 individual lithographic plates were separated from their binding and assembled into a full tapestry, with each plate measuring eleven inches by eighteen inches, the full map of the city would sprawl out to an eight-by-twenty-four-foot spread.

There are panoramic—or “city view” or “bird’s-eye view”—maps of nearly every American metropolis from this time period, though none is as precise, lucid, or sweeping as Dry’s portrait of St. Louis. In the nineteenth century, the single largest genre of printed lithographs comprised these city views. People craved vistas of their towns from above, whether they lived in Tacoma, Washington, or Trenton, New Jersey. Most of these maps show a similar arc of development, regardless of the city they depict: we can see an urban core along a waterfront in the foreground, a dense residential segment in the middle of the picture plane, tapering off into a variously rural landscape peppered with occasional dwellings in the background. The panoramas from this era show the seeds of urban expansion, radiating outward in rough concentric circles like the rings of a tree. We can usually predict the sprawling viral trajectory with which the emerging city will overtake the idyllic landscape, although St. Louis would prove to be a sad exception.

*

In the spring of 1874, Dry arrived in St. Louis to begin preliminary sketches for his map. He was one of the few dozen notable cartographer-artists who made a living charting the country’s rapidly expanding urbanism and feeding the national appetite for panoramic maps. In the three years before his arrival in Missouri, Dry was remarkably productive and had already drawn maps of nearly a dozen burgeoning communities throughout the southeastern US, with panoramas of Vicksburg, Mississippi; Galveston, Texas; Charleston, South Carolina; Raleigh, North Carolina; Norfolk, Virginia, and several others all bearing his imprint. The considerable scale of Pictorial St. Louis, both artistically and materially, made it a far more labor-intensive project than any of these previous maps. Anticipating today’s fusion of marketing and mapmaking technologies, the map’s publisher, Richard J. Compton, partially funded the map’s production by selling small advertisements for local businesses and industries—breweries, pork houses, brick works, and foundries, among others—which were numbered on the rooftops, indexed, and written up as paragraph-long footnotes. The index within the bound map-book featured 112 pages of these thinly disguised advertisements, which followed the 110 illustrated cartographic plates of the city view. The final product, which was fairly lavish in its production value, retailed at $25 per copy (around $530 today); many copies were sold through advance subscriptions that Compton had advertised in the local newspapers. In its time, the project undersold and ended up being a wash financially, more ruinous for Compton than for Dry, who appears to have suffered only a severe case of cartographer’s burnout after completing the drawing process. He would make his next map in 1903, some twenty-eight years later.

Very little of Dry’s life was documented; many historians treat him as a shifting phantom within the history of cartography. He was born in France in 1842 and came to the United States when he was twenty-one years old, enlisting in the US Army during the final stretch of the Civil War. He worked as a volunteer engineer in the fifteenth New York Regiment, Company F, and was assigned to a post as a draftsman in City Point, Virginia. In 1870 he married Caroline Louise Blocke in Louisiana. Thirteen years later, Dry signed on with the ill-fated Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique to assist in the first attempt at building the Panama Canal, which failed miserably. The date of his death is unknown, but a letter from 1914 postmarked Tarrytown, New York, the same year and place in which Caroline passed away, was, according to the distant descendent who deposited the slim biographical file at the Missouri History Museum, his last salvaged piece of correspondence.

The bulk of Dry’s cartographic output was accomplished in a five-year stretch during his early thirties, with ten maps produced between 1871 and 1875; this is also the period for which historians have the least biographical information about him. Aside from three stray daguerreotypes of a rigidly posed Dry—sessions from studios in assorted cities and from different eras of his life—perhaps the best portrait we have of the draftsman can be found in any one of the tiny, listless figures who wander his map of St. Louis.

*

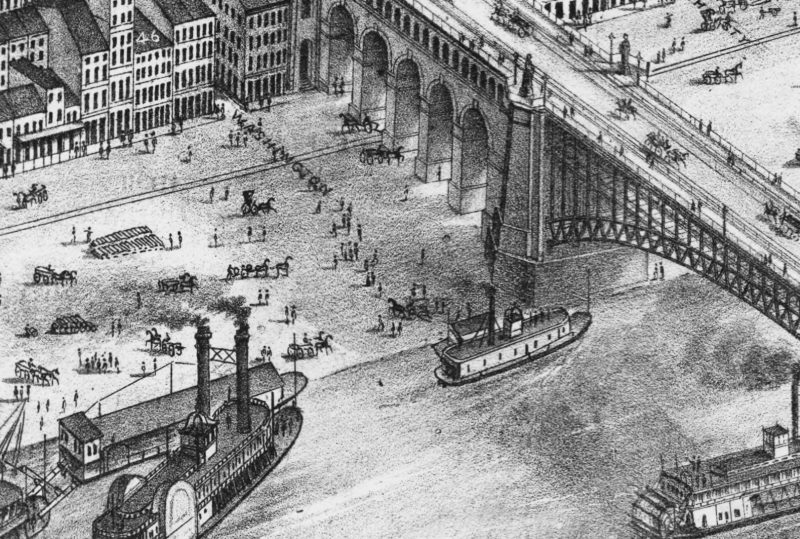

Even more astounding than the expansive scale of Dry’s map is the exactitude of its depictions. From an aerial view facing northwest—the same forty-five-degree angle as the rising sun—the entire city appears in one frozen mid-morning frame. We see shadows cast over downtown buildings, with their intricate and elaborate neo-Gothic and Romanesque Revival architectural flourishes. Thumb-pin-sized pedestrians wait to cross hectic streets and gather in hordes at outdoor markets. Columns of smoke rise from factories, boats, and breweries. Dozens of white open-air barges piled with raw materials float motionless on the flat Mississippi River, while clusters of steamboats with their company names clearly tattooed onto their hulls—u.s. mail line grand tower or e.o. smith—board orderly lines of passengers. Hundreds of horses are frozen mid-gallop and several long passenger trains hurl, immobilized, toward Union Station. Nearly every tree, mound, valley, and stream—along with every window, rooftop, row house, shack, fence, factory, bathhouse, alley, and bridge—within the boundaries of the city appears to have been inventoried and cataloged. With the lines so neatly drafted and the parallels of the streets so perfectly rendered, every square block could be seen as a drawer in a cabinet laid flat on its back, each containing the cluttered, itemized contents of the emerging metropolis.

The overwhelming intricacy and artistic sophistication of Dry’s map have inspired a small international cult following among designers, cartography enthusiasts, and amateur urban historians, and as a result the internet is rich with information about Pictorial St. Louis, including at least three sites that have pieced together digital composites of the 110 lithographic plates, presenting the entire map as a seamless and zoomable whole. My computer screen is smaller than a single page of Dry’s original map-book, yet these digitized versions allow the viewer to piece together the full city view in a resolution high enough to focus on details that would be difficult to see with the naked eye.

Traversing Pictorial St. Louis on a screen highlights the work’s strange parallels with contemporary digital mapping technologies. In the fall of 2012, Google released forty-five-degree satellite views of a handful of international cities. Where Google Maps had previously presented the viewer with either a flat, gridded perspective of cities as seen from above, or a purely horizontal “Street View” of city blocks, this new technique combined both perspectives. The forty-five-degree Google Maps view of St. Louis eerily echoes the panoramic map drawn by Camille Dry nearly a century and a half earlier. With the exception of the aerial view of Eero Saarinen’s Gateway Arch, the city’s sole true monument, which from above looks like a gilded parabolic totem, the pairing of Dry’s map with Google’s is uncanny in its mirroring effect. One need only observe a single location in the city on both maps, from a similar distance and angle, to take notice of the full scope of where the city has remained unchanged through the decades and where it has dramatically departed from the days when Dry surveyed it.

*

When Dry drafted his map of St. Louis, it was known as the “Fourth City,” trailing only New York, Philadelphia, and the then-independent Brooklyn in population. In 1870, its population was 310,864, according to the US Census from that year. Today, the city shares much in common with numerous other postindustrial Rust Belt cities, places that are all overly familiar with the effects of a long-term mass exodus. The city’s numbers peaked in 1950 at 856,796, followed by a steady decline that can be attributed to numerous interlinked social, racial, and economic factors. (The only other cities in the United States to have seen population declines higher than 60 percent since 1950 are Detroit and Youngstown, Ohio.) The population of St. Louis today is 318,172, barely more than what it was at the time of Dry’s documentation.

St. Louis, seen in the backward glance that Dry’s map provides, represents a strange disruption of the familiar narrative of urban expansion. As with any antique city map from this period, much of the pleasure of getting lost inside of Pictorial St. Louis resides in locating the many familiar buildings and landmarks that were then somewhat recent and that now linger as artifacts of a bygone era: the ornate Old Cathedral downtown, the intricate Eads Bridge crossing the Mississippi, the still-young Anheuser-Busch brewery, the thin three-story Victorian rowhouses that circle the stately grounds of Lafayette Square. Yet the bittersweet side of looking at Dry’s map from the perspective of the present comes from observing how large patches of the city have strangely and unexpectedly devolved. Whereas similar maps indicate a familiar trajectory of how a place gets from there to here, with strings of buildings gradually covering blank rural space, comparing Dry’s map to Google’s indicates how this kind of progress has reversed itself in contemporary St. Louis. Spaces that were once farms and orchards are now indeed sprawling neighborhoods and congested traffic corridors, yet many of the areas that were in Dry’s time thick with houses and markets and bustling action have grown into meadowlands once again.

Nowhere are these effects more striking than in the site of Pruitt-Igoe, once one of the largest and most notorious utopian experiments in public housing in the country, now a dense, fifty-seven-acre rectangle of pure, hemmed-in forest in the middle of the city. Designed by Minoru Yamasaki (who went on to build the World Trade Center) and completed in 1955, Pruitt-Igoe was a radical attempt at urban renewal. It was demolished in 1972—“the day that Modern Architecture died,” the architectural theorist Charles Jencks said of the spectacular demolition—due to widespread vacancy, high levels of crime and structural decay. On Dry’s map, near the exact center of Pruitt-Igoe’s future location, are a few square blocks of grassy field surrounded by lightly encroaching buildings; rural area becoming an urban space. Today, when viewed closely with the assistance of any of the free satellite-mapping services available online, this plot of land—in Dry’s time an intricately shaded black-and-white rendering and now a dense emerald patch—could almost pass for the interior of a national forest. All one can see in the contained space are vast, thick stands of trees jutting above the surrounding flat city blocks, effectively a city becoming wilderness again, probably even more wild than it was in Dry’s time.

*

Another parallel between Dry’s map and Google’s is the hundreds if not thousands of single figures standing awkwardly on street corners and at the edges of fields, seemingly in pure idleness. Unlike the pedestrians inadvertently captured by the ubiquitous roving Google Street View cars, all with blurred faces and harshly cropped bodies, the citizens wandering Pictorial St. Louis were placed in the scene with an author’s sense of intention. Though everyone in the absurdly broad tableau is captured spontaneously, as if through a distant snapshot, the details have been thoroughly worked over and sketched out. The reasons for portraying the varieties of labor are evident, as the map was partly intended to demonstrate the now-antiquated gears of the regional economy in action. But why include so many isolated figures standing idly on corners? Was the St. Louis of 1875 actually host to so many daydreamers, flaneurs, and cloud-gazers?

The fiction in such a portrayal is one element of the map’s charm. While a satellite can instantaneously frame any area at any time, Dry—most likely with a team of assistants—spent several weeks constructing his map. By using a viewpoint southeast of the city, across the Mississippi River in Illinois—possibly with the help of a hot-air balloon, though this seems to be up for debate as well—Dry was able to make a grid for the city, at 660 feet per inch, to evaluate the correct perspective to use in the drawing process. Each of these transposed grid-squares would later become the lithographic pages showing each quadrant of the city in the eventual map-book, a technique Dry describes in the work’s preface alongside a single page illustrating this cartographic method. From the high cross-river vantage point, he was able to render the array of precise architectural details on the dense plots of tall downtown buildings—high cornices and ornate rooftops that surely couldn’t be seen at the street level. The kind of geographic surveying performed by a camera-outfitted Google Street View car is merely an act of tracing, circling around the perimeters of buildings and blocks, whereas Dry’s process was truly an act of filling in, grid by grid, the full depth of the city at a given—albeit an artificial—moment.

With such a laborious method, the possibility of showing the entirety of a city in a single instant can only be imagined. Even if some of the figures in Dry’s grid were actual people, his view of the city as a whole is necessarily a quilted composite, both of passing days and of people’s movements through space. The man balancing a stack of boxes on horseback in one plate could be one of those daydreaming loiterers in another. And yet this fictive quality of the map in no way diminishes its cartographic facticity. Like all great works of art, Pictorial St. Louis goes through great pains to describe the world with utmost care and accuracy, while simultaneously reinventing and reimagining it as a site of speculation and wonder.