Rarely have we seen such a neurotic antihero in a revisionist western as Eli Sisters of The Sisters Brothers. Encumbered less by loyalty than by his own wanting self-worth, Eli suffers from loneliness, longing for the companionship of a woman. Laboring in the shadow of his irreproachably masculine outlaw brother, Charlie, he confesses to rarely having known a woman longer than a night; even with prostitutes, he favors discourse over intercourse. At one point Eli admits, “I saw my bulky person in the windows of the passing storefronts and wondered, When will that man there find himself to be loved?”

Eli does not share his brother’s love for whiskey and whorehouses. He is fastidious about his health. He is worried about his weight and cares achingly for his horse. After a dentist gives him tooth powder and a toothbrush, a new invention at the time, he shows it to a woman he is trying to impress; excitedly, she retrieves her toothbrush so that they can brush their teeth together. “So it was that we stood side by side at the wash basin,” he reflects, “our mouths filling with foam, smiling as we worked.”

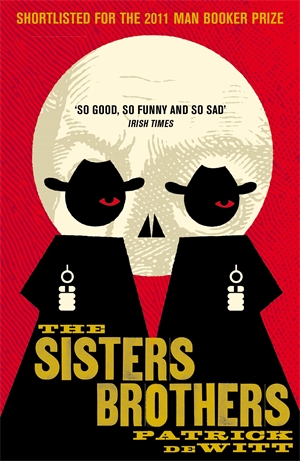

The Sisters Brothers is not the typical western, which (with the possible exceptions of Little Big Man and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) rarely makes use of humor as a convention, particularly a humor so absurd. But Patrick deWitt has found a way to isolate and quarantine the conventions of the traditional revisionist western, permitting himself a degree of risk-taking that leaves the reader no less aware of his fearlessness. Eli’s neuroticism is both humorous and sad; we’re not sure whether we should laugh at him or fear him.

Eli is dangerous by reputation, though, and people do fear him—his romantic idealism is an impediment only to Charlie, who is inordinately fixated by his own sheer lust for women and booze and money. Charlie is brutal and invasive, always demanding to make decisions and be in charge—in a sense, the typical outlaw, the human Yosemite Sam. Yet Eli never backs down. Early in the novel, while traveling on horseback, he sings a “mawkish ballad” meant only to irritate Charlie in a brotherly manner:

“His tears behind a veil of flowers, the news came in from town.”

“Oh, all right.”

“His virgin seen near country bower, in arms of golden down.”

“You are only angry with me for taking the lead position.”

“His heart mistook her smile for kindness, and now he pays the cost.”

“I’m through talking with you about it.”

“His woman lain in sin, her highness, endless love is lost.”

Despite his shortcomings, Charlie remains likable as well. The brothers’ personalities are vastly different, yet both are appealing, and so we root for them. We want them to survive, to rob, to win their fights. At times we forget their mission is to kill—until deWitt reels us back in with a reminder, at just the right time, that this is what Eli and Charlie are hired to do.

If an audience is not morally dubious about its attachment to hardened criminal protagonists—think of Tony Soprano or Vito Corleone—it is often because those criminals are likable: no matter what evil they do, they are human, and we see in them what we see in ourselves. More than his superior rendering of voice and sensibility, and the campaign his dialogue carries on against long stretches of exposition—“I had resolved to cease filling myself so gluttonously, that I might trim my middle down to a more suitable shape and weight. Charlie was groggy but glad, and wanted to make friends with me. Pointing his knife at my face he asked, ‘Remember how you got your freckles?’”—deWitt’s chief accomplishment is creating sympathetic meaning in two dangerous men united in a journey toward violence. His skill with moral ambiguity is no less remarkable given that he applies it to a genre that traditionally has little use for it.