I. The Heartsnatcher

Boris Vian—poet, novelist, jazz lyricist—appears on the screen in the fifth minute of Roger Vadim’s 1959 Les liaisons dangereuses. In the minor role of a French foreign minister, Vian accuses Jeanne Moreau of ignoring him. She argues to the contrary that she likes him a lot. Her remark “hurts his heart,” Vian replies.

“Oh, you have one?” she asks.

Yes, he does, since the moment that her husband introduced them.

“Be grateful,” Jeanne Moreau answers, “hearts are scarce these days.”

A minor film appearance would be a silly place to begin a survey of a career as kaleidoscopic as M. Vian’s, were it not for the fact that the cinema killed him. Legend has it that at a private showing of the unauthorized film adaptation of his controversial novel I Spit on Your Graves (also 1959), the actors’ lousy performances allegedly provoked him to exclaim, “These guys are supposed to be American? My ass!”1—whereupon he dropped dead of a heart attack. He was thirty-nine.

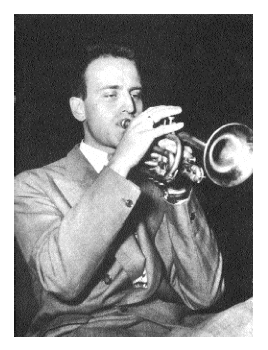

For a man of such a frail constitution, Vian was restlessly active throughout his life. Born in Ville d’Avray, France, in 1920, Vian endured a malady-riddled childhood that left him with a weakened heart. This organ, an instrument of life, he knew would also cause his death, a realization that colored everything to which he turned his attention (that is to say, a considerable lot). During World War II, he trained as an engineer, wrote a couple of novels, and played jazz trumpet with amateur nightclub bands. This love of jazz (and a good time) put him at the center of the newly liberated postwar renaissance. Vian literally wrote the manual on Saint-Germain-des-Prés,2 the neighborhood over which the stars momentarily aligned to concentrate the terrestrial cool. He knew everyone: Jean-Paul Sartre, Alberto Giacometti, surrealist Georges Hugnet. His friends and admirers included literary superstars Raymond Queneau, Jacques Prévert, and Albert Camus. In the fourteen years of his literary career, Vian himself wrote at least ten novels and forty-two short stories, four collections of poetry, seven plays, six opera librettos, fifty-plus journalistic articles, and translated twenty works from English, including novels by Raymond Chandler, Nelson Algren, and the five-hundred-page memoir of General Omar Bradley, which he reportedly completed in two weeks.

But his literary work failed to achieve the same reputation as that of contemporaries like Alain Robbe-Grillet or Nathalie Sarraute. Vian’s four pseudonymous pulp novels, however, did gain critical mass: they were so scandalous that everyone wanted a copy (and so scandalous that he was taken to court and fined for outraging public morals). Plenty of admirable authors start out writing pulp (Kurt Vonnegut, David Markson). Some raise it to the level of art (Raymond Chandler, Georges Simenon). Very few begin writing pulp, hit their stride writing literature—and then decide to give it up to be the French Cole Porter. In 1953, Boris Vian abandoned fiction and began a second career as a lyricist, writing more than four hundred songs in the six years before his death. His is one of the unlikeliest and most diverse careers in literature.

II. The Dead All Have the Same Skin.3

It began with Vian’s succès de scandale, his novel J’irai cracher sur vos tombes (I Spit on Your Graves).4 His first work in print was, if not precisely his own, the centerpiece of one of the better literary hoaxes of the twentieth century (although, by his own admission, it “hardly deserves attention, from a literary viewpoint”).5 This lurid potboiler was written in French in the summer of 1946 on a lark. A friend’s fledgling publishing house, Editions du Scorpion, asked Vian for a translation of an American pulp novel, so Vian wrote his own. They passed it off as a translation of an American thriller written by a (fictitious) African American named Vernon Sullivan, who hadn’t found an American publisher. The book was a tremendous best seller in the spring of 1947, largely because of two well-timed scandals: the first, in the fine French legal tradition of Zola and Flaubert, involved a lawsuit that sought to ban the novel, followed in April by the discovery of a copy of the book in a murderer’s hotel room, with appropriately murderous passages circled. Three other Vernon Sullivan books followed. By 1953, when Vian stopped writing fiction, it was generally known that Vernon Sullivan was himself a fiction.

Vian’s inspiration came in part from Faulkner and American crime fiction, and in part from his association with black American jazz musicians. Vian was keenly aware of the abuse suffered by black Americans, because he heard about it from his friends and saw it practiced (in one of his jazz columns, he deplores the epithets shouted during a Dizzy Gillespie concert in France). If his heart was in the right place, his craft was not. Spit’s story is one of blind revenge: the black narrator’s brother is killed, his family scattered, and he decides to take the lives of two rich white sisters as retribution. The plot is nearly senseless. Vian had never been to America, so his descriptions of scene and costume are vague,

his geography is inscrutable, and

his presentation of racism is a simplistic caricature (making Richard Wright’s Native Son seem by comparison a masterpiece of subtlety). The book is more provocative in its misogyny than in its racism, as its narrator spends most of his time seducing high-school girls rather than manifesting anything like a thirst for justice.

Whatever its faults, the novel is typically Vianian. Stylistically, reality and verisimilitude are beside the point; causes are divorced from their effects; the narrative point of view switches at the last minute; and everyone dies in the end.

Which brings us to Death.

Vian’s work, even his “throwaways,” is marked by an enthusiasm for life, a hedonistic gusto and

a righteous, quasipolitical6 anger against war and injustice. So it might seem a contradiction that his characters, minor and major, should die so brutally and offhandedly. It’s easy to mistake for cruelty what is a profound sympathy. His novel Heartsnatcher features the crucifixion of a stallion in enough vivid, passionate detail to rival what Northern Renaissance painters reserved for Easter altarpieces. Vian always intends to inspire this horrified dismay, that a life could be destroyed for any reason, especially those as inane as bureaucracy, religion, greed, politics, stubbornness, or simple stupidity. Throughout Vian’s œuvre the agent of death is often an authority figure. Police, employers, lawyers are all selfish and brutal, abusive, and exploitative, for no reason but that they can be. In his short story “Journey to Khonostrov,”7 authority is the mob (or, if you prefer, democracy). Five strangers on a train torture and mutilate a sixth, Saturn Lamiel, because he refuses to converse with them. No reason is given for Saturn’s refusal (except that he is, obviously, saturnine), and he endures their abuse with an implacable lassitude. As they arrive at the station in Khonostrov, Saturn awakes and remarks, “I’m not too talkative, am I?” as blood sloshes “in every corner.” Then the story abruptly ends. This is “Bartleby the Scrivener” reimagined: in Vian’s version, the penalty is more swift and painful than expulsion and starvation. Here the nonconformist has a blowtorch taken to his feet and his left ass-cheek amputated. If Vian has a theme, literary or biographical, it is how to live under threat of Death, sudden, indifferent, and capricious.

III. The Pathetic Fallacy, without the Fallacy

Vian’s literary work owes a debt to the surrealists for its strangeness. But a closer audit of the accounts reveals that they’re not really trading in the same currency. Vian’s images are neither arbitrary nor aleatory, and his language makes no attempt to excavate the subconscious mind. Instead he mines the language itself to create associations.

Vian’s characters inhabit a fertile linguistic territory between the literal and the metaphorical. The fabric of Vian’s fictional worlds is subject to his characters’ emotional and psychological states. For example, in one of Vian’s lovelier passages from his novel L’Ecume des jours,8 a heartbroken young gentleman is moping outside a friend’s party when he sees two girls pass by and enter the house: “His heart swelled up to ten times its normal size, became completely weightless, lifted him up above the earth, and he went straight in after them.” Vian is not simply being lyrical when he says the young man’s heart lifted him off the earth—Vian means that his heart lifted him off the earth. A character’s emotions and the language used to bring those emotions into existence persist as both sign and signified in palimpsest, visible through one another. One thing is rarely “like” another, unless that other thing is distractingly impossible, and his metaphors are more lyrical and evocative than descriptive. Or as Vian puts it in his foreword to L’Ecume, the book’s “material expression… is a projection of reality, under favorable circumstances, on to an irregularly tilting, and consequently distorting, plane of reference.” His influences are closer to science fiction, with its allegory and symbolism. Vian is closer to his friend Raymond Queneau, who shares a love of wordplay and puns, exulting in the generative possibilities of verbal ambiguity. Reading Vian quickly makes one realize it is utterly beside the point to talk about “reality” when talking about fiction.

Queneau described L’Ecume des jours as “the most heartbreakingly poignant modern love story ever written.” During and after his lifetime, it has been the most successful of Vian’s novels and is the lynchpin of his literary reputation. Vian declares in his foreword, “only two things really matter—there’s love… and there’s the music of Duke Ellington.” This novel takes up the subject of the former, incorporating the major themes of his short stories—the cost of desire, life in the shadow of death—with a more sophisticated twist. Police are still murderous, jackbooted thugs; doctors are still quacks and butchers in equal measure; and work is still soul-crushing in all its forms. But L’Ecume offers the harsher truth, that even in a perfect world no one is immune to misfortune, and there is no one to hold to account.

Colin is rich. He has a beautiful apartment where the mice are well groomed and sunlight comes to frolic. He has money, friends, and a suave valet. The only thing missing is love. Then Colin meets Chloe, and they fall instantly in love: whirlwind courtship, big church wedding, attenuated honeymoon. Throughout the book, Chloe is surrounded by flowers (her name is Greek for “tender bud”). Out of some perverse affinity, a parasitic water lily nests in her lung, weakens her health, and destroys the young couple’s life together. Their beautiful apartment deteriorates—the windows shrink and close up; “half-vegetable, half-mineral projections” descend from the lowering ceiling; the mice turn gray and visibly sadden; the sunlight tarnishes. Colin has to sell his possessions and take a job (the ultimate sacrifice) to pay for his wife’s treatments.9 Love drives Colin to sacrifice everything for Chloe, even though she can’t be saved.

Not even the well-groomed mouse escapes. His loyalty to Colin drives him to a heartfelt (if illogical) sacrificial bargain with a cat, who in return for eating the mouse will do something to help Colin, starving to death in his grief.

The dilemma that Vian feels so strongly is that love, one of “only two things [that] really matter,” is sacrifice, and an ineffectual one. No one escapes. What keeps L’Ecume (and all of Vian’s work) from turning into the lugubrious melodrama of a Thomas Hardy novel is the lightness and wit of Vian’s prose. When one character says with resignation, “That’s life,” Colin counters, “It isn’t.” Vian disavowed any existentialist affinities with his friend Sartre. Vian loved all of life, even as he recognized its cruelty. L’Ecume blossoms with vivacity and sadness.

IV. Of Loving Unwisely and Unwell

Written later in the same year (1946), Vian’s next novel, L’Autumne à pékin (Autumn in Peking),10 can be read as as the twisted, Fatal Attraction version of L’Ecume. A group of men labor in the desert of Exopotamie to build a railroad (not to any place), while a love triangle slowly builds to a conflict among three friends. Also on the scene (perhaps best imagined in the tenor of a Sergio Leone film) are an abbot and his loose society of hermits, the big hotel where everyone lives, a doctor who builds model planes, and the archaeological excavation in the backyard. Everything around them is desert. The love triangle depends primarily on Angel, who loves Rochelle deeply and resents that his friend Anne (a man) is using her for sex. Bit by bit the railroad gets built, its route taking it directly through the middle of the hotel (and over the underground archaeological site). Meanwhile Angel worries that Anne’s attentions are physically degrading Rochelle. Just as Anne is about to give her up, Angel kills them both.

Autumn is a novel of oppositions: doctors whose main therapeutic gesture is mercy killing; the hermit whose saintly act is fornication; bureaucracy vs. labor; love vs. lust; and the industrial railroad vs. the archaeological excavation. By far the most surreptitious and allusive of Vian’s novels, Autumn is also fortunately the most declamatory. Characters explicate their philosophies in profound conversations in order to compensate for the narrative’s arcana. The novel has the sort of intensity one might recognize in the late-night conversation of precocious college freshmen earnestly debating profound metaphysical issues one minute and girls the next. Girls specifically, because Autumn is a guy’s book. Its sexual politics (not to say Vian’s) are as bohemian, clichéd, and French as a man in a beret with a baguette in one hand and a glass of Beaujolais in the other. If one can look past its chauvinism (not to say Vian’s), it is studded with pithy aphorisms (“it happens that in our flesh, we are deceived”) and side characters who largely redeem the frustrating protagonist.written later in the same year (1946), Vian’s next novel, L’Autumne à pékin (Autumn in Peking),10 can be read as as the twisted, Fatal Attraction version of L’Ecume. A group of men labor in the desert of Exopotamie to build a railroad (not to any place), while a love triangle slowly builds to a conflict among three friends. Also on the scene (perhaps best imagined in the tenor of a Sergio Leone film) are an abbot and his loose society of hermits, the big hotel where everyone lives, a doctor who builds model planes, and the archaeological excavation in the backyard. Everything around them is desert. The love triangle depends primarily on Angel, who loves Rochelle deeply and resents that his friend Anne (a man) is using her for sex. Bit by bit the railroad gets built, its route taking it directly through the middle of the hotel (and over the underground archaeological site). Meanwhile Angel worries that Anne’s attentions are physically degrading Rochelle. Just as Anne is about to give her up, Angel kills them both.

V. Glory Hallelujah

L’Arrache-coeur (Heartsnatcher)11 is the last of Vian’s fiction. His least plot-driven book, it unfolds in three parts, a meandering, entirely wonderful, often appalling series of vignettes. It begins with one of the oldest narrative tropes in literary history: one morning, a mysterious stranger comes to town. But this stranger will change no one’s life nor purge the town of its depravity. The psychiatrist Timortis arrives with no history and no desires. All he wants is “to have envies and desires of my own—and I shall take them from other people… I want to bring about some kind of transference of identity.”12 Timortis gets a home with Angel and Clementine as a reward for helping the latter deliver the triplets Noel, Joel, and Alfa Romeo. But from the pain, Clementine has also given birth to a loathing of her husband and of physical contact.

Timortis’s project of identity vampirism also fares badly. A great deal of his time is spent running errands and seeing the sights in town: the Old Folks Fair, where the aged are auctioned off; the egg-shaped church, where the town vicar boxes the Devil in an exhibition match; the carpenter’s shop, where apprentices collapse from abuse; and the boatman Glory Hallelujah, who fishes severed limbs out of a river of blood with his teeth. It is Glory Hallelujah’s fate to shoulder all of the town’s shame, allowing it to behave as horribly as it does. It is Glory Hallelujah with whom Timortis finally connects, and whose mantle he assumes when Hallelujah dies.

Meanwhile Noel, Joel, and Alfa Romeo learn to talk, to walk, and to fly. Overprotectiveness compels Clementine (ignorant of their gifts) to slaughter the trees in the garden, to clean her boys’ bottoms with her tongue, and to surround the house with a barrier of Nothingness. Clementine is another dark face of love—or Mother as the Ur-authority figure—who denies her children experience, with its inherent risks, smothering them in the name of love.

Vian’s verbal play and lush, spontaneous imagination are at their peak in Heartsnatcher. The images are arresting and poetic, the language is exuberant. By contrast, the characters are restless, in search of release from fear and desire. Sadly, Clementine and Timortis finally manage to achieve that stasis, which may in fact be worse than death. It’s not a cautionary tale, but a study of the unavoidable dilemmas of desire, love, and pain. Vian’s insight is that they are all inextricably bound up together.

Through the three novels one can detect a maturation of style and an increase in cynicism. Love against the outside—love against itself—finally, love perverted into oppression. Which is not to say that Vian underwent a corresponding shift in his biography, only that his fiction charts asymptotically closer to nihilism, with only his prose style to buoy the mood. It might be this, in addition to the novels’ poor reception, that persuaded him to focus on the performative. In his lyrics and plays, the serious and farcical comfortably blend without the complications of plot or desire.

VI. It All Goes in the Hole.

His politics are most visible in his plays, The Knacker’s ABCs (1950), The General’s Tea Party (1962), and The Empire Builders (1959). The first two are broad satires in the spirit of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu plays or, at a stretch, Aristophanes’ Lysistrata. They are deeply political, and although their targets are the military and war, these plays are concerned more pointedly with the human foibles behind them.

The Knacker’s ABCs (subtitled in English “a paramilitary vaudeville in one long act”) crystallizes the recurring Vianian theme of the Pit. What began in L’Ecume as the sewer under the Medical Quarter and became the river of blood in Heartsnatcher is here literally the knacker’s pit. In the play, a horse butcher from Normandy and his family prepare to celebrate the nuptials of daughter Marie to a German soldier (both daughters and the mother are all named Marie) during the Allied invasion. American, German, and French soldiers wander in and out during the action as bombs explode offstage. To describe the plot, such as it is, is an exercise in blocking, a carousel of characters in constant rotation, an important side-effect of which is to demonstrate Vian’s understanding of the human condition. His characters are unique, yet interchangeable (multiple Maries, an apprentice compelled to cross-dress, soldiers trading uniforms and accents). They all desire the same things—sex, primarily, and a bit of respect—and all are destined for the same end: a grave in a stinking pit of slaughtered horse parts. They get tossed in one at a time as they get knocked out. For a finale the entire set explodes, and everyone dies. It’s a heartfelt farce, almost Chaplin-esque: Noises Off set during World War II.

The most often staged of Vian’s plays, The Empire Builders has more in common with Ionesco’s Rhinoceros and other absurdist theater than with Vian’s other works. It is his last literary work and was not staged until after his death. It is a dark, cynical, satirical allegory in which a former horse butcher, living with his wife, his daughter Zenobia, and a maid named Mug, is pursued by a mysterious piercing Noise. It drives the family upward through the building, into smaller and smaller apartments over the course of three acts. They gradually abandon their belongings and each other, until only the father is left. Alone in a garret, wearing his military uniform and holding his pistol, he confronts the Schmürz.13 The Schmürz (part mummy, part lethargic zombie) has accompanied them from the beginning, mute, indestructible, passive but persistent. Like the Noise, it menaces largely through its indomitable Otherness. The daughter is the only character who openly acknowledges its existence, while the others affect total ignorance, even as they pummel and physically abuse it. The family’s ambitiously bourgeois lifestyle and the father’s military past (“the empire builders”) are the key to the play. In light of the turbulent political climate of 1950s France, when colonial outposts in North Africa and Indochina were in open revolt, the Schmürz is a mangled every-victim, confronting the beneficiaries of its exploitation in their own living rooms. The father, although willfully blind and amnesiac, cannot escape a direct confrontation. Alone at the end, the father strangles and shoots his silent, resilient visitor, who refuses to die. The Noise grows louder, a final sounding, sending the father nearly out the window. As the curtain descends, other shadowy Schmürz-like figures invade the stage. The consequences of being caught by the Noise or overwhelmed by the Schmürz are never made clear… but one can imagine it is the Pit rising, rather than waiting, to meet the characters.

Vian’s outraged pacifism infected even his pop songs. “Le deserteur” (first performed in 1954) is sung as a letter to the French president, wherein the singer refuses to go to war and “kill wretched people.”14 The song, written as a reaction against the French war in Algeria, threatened to detonate Vian’s nascent career as a crooner. Because of its politically volatile lyrics, the song was banned from the radio and production of the entire album discontinued by the label. Later the French pop star Mouloudji would change the ending slightly and popularize the song, which led to its adoption by American pacifist folksingers like Joan Baez and Peter, Paul and Mary.

VII. Songs Possible and Impossible

Vian wrote his first song, “Au bon vieux temps,” in the winter of 1943, in a style of “comic-realism of old black Southern songs.”15 His passion for jazz began at age seventeen, the same age he took up the trumpet; by 1942 he was playing in an amateur jazz orchestra at the club Tabou in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Through the late ’40s and early ’50s, Vian was writing criticism for the magazines Jazz Hot, Camus’s Combat, and Jazz News. His articles16 embody the same wit and irreverence found in his other work, and even occasionally manifest the same morbidity (for example, one article is titled “Should All White Jazz Musicians Be Executed?”). Vian’s is an uncomplicated, contagious enthusiasm, a criticism without agenda or malice. As he explains himself, “What are critics really after? I can speak only for myself, but I know what I’m looking for: to increase demand, for more opportunities to listen to Ellington, Parker, Gillespie, Louis, Ella, Peterson and the others… The audience knows or doesn’t know what jazz is. The critic merely helps them know a tiny little bit more.”

At the same time, he was writing songs and performing as a singer (his health had forced him to give up the trumpet in 1950); and he was writing plays, operas, and musicals. In 1955 Vian recorded his lyrics for a pair of 45s, “Possible Songs” and “Impossible Songs.” Among the tracks were his more famous songs “Complainte du progrès,” “J’suis snob,” “La Java des bombes atomiques,” and the infamous “Le Deserteur.” Vian worked for record labels Philips and Barclay in the late ’50s, producing jazz anthologies and writing songs like “J’coûte cher” and “Rock and roll-mops” for French singers.

Vian’s songs fill almost a thousand pages, constituting an entire volume of his complete works, with titles and tones ranging from (in English) the sweet “A little love and sentiment” to “I have no regrets” to the self-explanatory “I’m a perverse monster.” According to musical accomplice Henri Salvador, Vian didn’t like writing love songs, dismissing them as “cucul,” or corny. His songs rather are about politics and passions: the joy of going to the movies, of vacations, of being twenty (“J’ai vingt ans, la vie est belle”), of drinking to forget, and of the atomic bomb (along the lines of Randy Newman’s “Political Science”). Vian even wrote a pro-feminist song, exhorting women not to give up the joys of the single life for unions with the unreliable gender. The complexity of Vian’s language, with its puns and neologisms, diminishes along with the psychological complexity of his work. In the songs and plays he seems almost to set aside language so he can express his humor and politics artfully but unabashedly.

VIII. “In Our Flesh, We Are Deceived.”

Vian appears once more in Les liaisons dangereuses, only for a minute, in the scene just after Valmont’s seduction of the gullible Marianne.

The whole melodrama from here unfolds in a way all too familiar to Vian: aristocrats exercising power in depraved and capricious ways; a cascade of improbably plotted betrayals; an impeccable beauty pouting gorgeously in soft focus, waiting to go insane; and a fatal head-wound impending at a party across town in the form of an innocent brick by a fireplace. All of which is set to a soundtrack by Thelonious Monk and Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

As his final scene is drawing to a close, Vian grabs his coat to leave for a meeting, and Valmont asks, “Do you know the way?”

Vian answers: “By heart.”