In 1532 an Italian fellow named Viglius wrote to a friend about his upcoming trip to Venice, where he planned to see the new invention that was currently obsessing the medieval cognoscenti: the Theater of Memory. He wasn’t entirely sure what the Theater of Memory was but had heard that it was “a work of wonderful skill, into which whoever is admitted as spectator will be able to discourse on any subject no less fluently than Cicero.”

When he returned from Venice a few weeks later, Viglius wrote again to tell his friend what he had seen. “The work is of wood,” he wrote, “marked with many images, and full of little boxes.” The “theater” turned out to be a contraption the size of a small room, housing an apparatus with gears and a series of little wooden windows that opened and closed to reveal various words and images etched inside. By manipulating the windows, a visitor could retrieve nuggets of information on any number of topics: the seven virtues and vices, the teachings of Solomon, the orientation of celestial bodies, and all manner of other medieval factoids. The Theater’s inventor, a fellow named Giulio Camillo, “calls this theatre of his by many names,” wrote Viglius, “saying now that it is a built or constructed mind and soul, and now that it is a windowed one.”

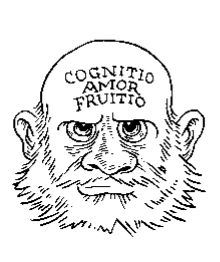

Camillo had created a device that captivated the literate Venetian public, but the invention was not entirely his own. In truth, the Theater was a cheap factotum of an old monastic trick: the Art of Memory. In its original incarnation, the Art had required no physical equipment; it was strictly a mental regimen, involving an arduous training program that allowed cloistered monks (with no shortage of time on their hands) to pass their days memorizing the scriptures, religious commentaries, and assorted classical works. The technique worked something like this: A monk would apprentice himself to a master of the Art, who would teach him the technique of visualizing a great house or palace filled with a number of rooms. Each room contained a series of symbolic objects tied to a theme. For example, a room devoted to theology might play host to (surprise) a theologian, his head tattooed with the words cognitio, amor, fruitio, his limbs with the words essentia divina, actus, forma, relatio, articula, precepta, sacramenta, and so on. The trainee would learn to make a painstaking journey from room to room, visualizing each object, marking, learning, and inwardly digesting the metaphorical interior design.

It took dedicated monks years to master the Art, but those who did reported astonishing mnemonic feats. One fellow claimed to have memorized more than one hundred thousand rooms, enabling him to recall the entire canon law, two hundred complete speeches by Cicero, three hundred philosophical sayings, twenty thousand legal points, and more. Another practitioner devised a system that would allow the student to learn every known fact of theology, metaphysics, law, astronomy, geometry, arithmetic, music, logic, rhetoric, and grammar. Over the centuries, the practice yielded increasingly elaborate exercises that often devolved into a kind of exponential crossword puzzle: an endless source of diversion for the solitary monk whiling away long days in his cell.

By the sixteenth century, the old monastic wisdom traditions were starting to find their way out of the cloisters and into the city streets. In the wake of Gutenberg, Europe was undergoing a convulsive information explosion. The old medieval knowledge systems, with their cathedrals of grotesque imagery and esoteric theaters of memory, looked increasingly quaint and abstruse. Gothic cathedrals were now competing with plain white Lutheran churches. Illuminated manuscripts were giving way to the new mass-produced vernacular Bibles. And the old scholastic Art of Memory would soon decline in the face of a new empirical scientific method. There would be no room for memory palaces and tattooed theologians. Writers like Erasmus scorned the old Art of Memory as “an example of those cobwebs in monkish minds which new brooms must sweep away.” In sixteenth-century Venice, however, a few of those cobwebs lingered.

Camillo was a former monk himself, who had left the monastery to seek his fortune in the town square. Determined to make something of himself, he hit upon the idea of taking the old Art and cashiering it into a device suitable for public consumption. He even came up with a catchy tagline: turning “scholars into spectators.”

No one knows exactly what Camillo’s Theater looked like—no drawings have survived—but he once described it as follows:

Following the order of the creation of the world, we shall place on the first levels the more natural things. Those we can imagine to have been created before all other things by divine decree. Then we shall arrange from level to level those that followed after, in such a way that in the seventh, that is, the last and highest level shall sit all the arts.

Proceeding from the physical chassis of the Theater, to the metaphorical house of wisdom, then upward through a series of associations to the celestial realms, and finally to the arts, the Theater gives us a glimpse of how the internal Art of Memory must have worked: proceeding from the gross physical plane of the windows to successive layers of abstraction, ultimately ascending to a transcendental understanding of celestial truths and the secrets of the arts. It was a stairway to the stars.

For newly literate Venetians, Camillo’s technological innovation must have offered a tantalizing proposition. Step inside, click open a window or two, and presto: the world’s wisdom revealed. No need for those plodding old monastic mind games. But was it really a “constructed mind,” let alone a “soul”?

For all the popular attention his Theater received, Camillo never actually finished it. The version he showed to the public was really just a demo. Like many an entrepreneur, he had designed a proof of concept to sell investors on his idea, hoping to raise funds so he could finish the project. In those days, the closest thing on the medieval Continent to a venture capitalist was the King of France, who granted Camillo a seed funding round of five hundred ducats. The project ran way over budget, however. Ultimately Camillo burned through more than fifteen hundred ducats before he finally had to pack it in. During it all, Camillo kept up a happy face, ensuring friends that the king was bound to reward him handsomely once he witnessed the fruits of his labors.

The king never gave him another ducat. Camillo never saw his reward. He died without ever completing the project, or finishing the great treatise that he promised would lay bare his secret algorithms. Nor, let it be noted, did he or any of his patrons ever become as smart as Cicero. Camillo died in obscurity, and Cicero is still Cicero. In the end, all he had to show was an unfinished contraption, full of boxes and windows.