In Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud famously compares the structure of the unconscious to Rome’s many strata of buried ruins. In the opening lines of A Series of Small Boxes, Thomas Devaney invokes a Rome that’s equal parts real and remembered, actual and written. In an age when various political and religious figures promise to deliver truth in the guise of salvation, poetry may be better off working the gap between fact and the imaginary, albeit without making compassion and doubt subservient to fancy. “You don’t have to get abstract to see everyone’s beat-up badly. / It’s not the future it’s Lunchtime all around.” The modesty—here also defined to mean generous and encompassing—of Devaney’s poetry is an awareness of the slow, deliberate effort it takes to create a better world.

Similarly, life may approximate the accumulation of sediment more than any heroic process of building, reconstruction, or dismantling: “our ephemera often have a hold well beyond their spheres.” The silt of experience seeps, deepens, and redirects during its conversion into memory, but it does so without any guarantee of accompanying clarity or insight (which is precisely where Freud saw his opportunity): “Dirty waters found us before we found them. / It might sound obvious, but by the time everyone knew, / there was no one to tell.” Devaney’s poems carefully gather the particles of everyday encounters: DVD titles, a satisfying meal, reports from Iraq, interactions with friends and family, the sound of birdcalls, the memory of “Milton, bacon, your face in a year of rain.”

Although Devaney titles one of the book’s most striking poems “Trying to live as if it were morning,” you don’t just wake up one day and suddenly change your life. Instead, you gradually develop some self-reflective distance from it, and learn to manage and negotiate the psychic crap you thought would eventually disappear with age. A Series of Small Boxes seeks this breathing room in a number of ways, whether through repetition, deadpan juxtapositions, or the complication of perspective: “We had a hard time with time. / We weren’t the we we thought.” Identity can be a shaky thing and frequently relies on external confirmation. Yet the opened spaces in Devaney’s work also generate a sense of loss that overrides the poems’ personal dedications, just as addressing someone in writing—perhaps writing itself—implies a prior absence.

Devaney recommends the use of small boxes to negotiate this loss, whereas larger ones indicate that which is taken away, whether during childhood or amid increasingly disheartening attempts to be a citizen in the world: “My best advice has always been small boxes. / So we move. Pack your songs, fringe history of television, / kindergarten constructions, extra socks, somehow it all will fit; / and what doesn’t you can bring along too, if you’d like…. / Big boxes cast big shadows, but let’s be clear: / big boxes are not the opposite of small boxes. / These boat-sized boxes have their place / in the real estate of the world.”

Blurring the boundaries between public and private, Devaney’s poetry rarely ventures far from the quotidian concerns, struggles, triumphs, and failures that only seem monumental when viewed from too close up—that is, when they’re not put into relation with the experiences of others. Home may remain contingent, at least for now. That’s what the boxes—and poetry—are for.

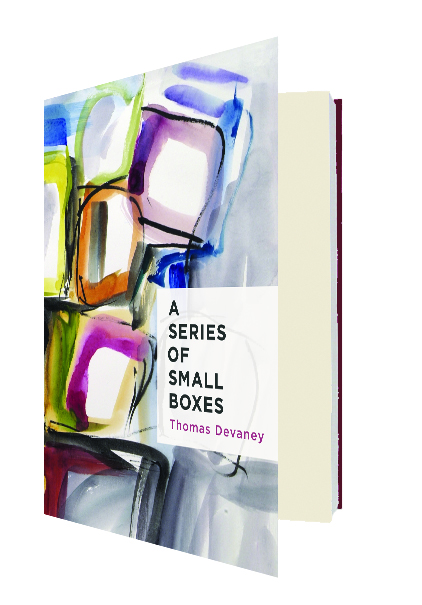

Format: 68 pp., paperback; Price: $15.00; Size: 6″ x 9″; Publisher: Fish Drum; Editor: Suzi Winson; Print run: 1,000; Book designer: Basia Grocholski; Typeface: Meta; Image featured on the cover: Abstract paintings of boxes by the publisher’s mother; Total number of poems in the book: 34; Number with dedications: 17; Activity about which the author appears to be conflicted: Miniature golf; Things Obi-Wan Kenobi valued late in life, according to a poem titled after him: “Comfortable shoes” and “a good haircut”; Representative line: “New Jersey is the greatest poem never written.”