FEATURES:

- Speaks Spanish, English, and French

- Batteries included

- Not dishwasher-safe

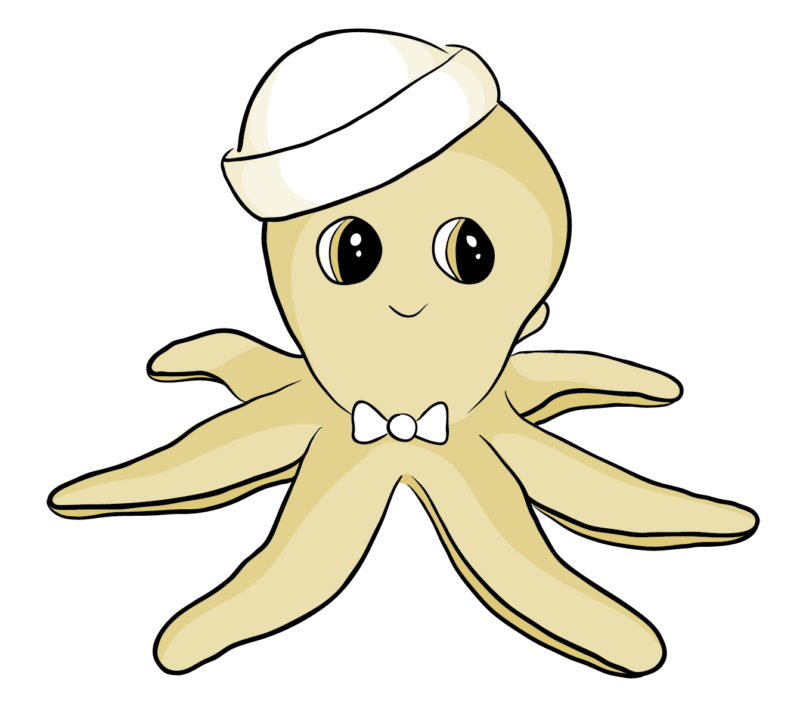

Its body is light blue and 100 percent synthetic. It’s a good-natured and naive octopus, and its smile is genuine. Its eyebrows are green, as are the two blushing spots on its cheeks. It weighs 11.4 ounces. It’s clearly intelligent—as nearly all octopuses are, of course. It wears a bow tie, and a sailor’s cap is cocked rakishly just a little to the left. If you squeeze the animal’s head (which is objectively small, but enormous compared to its body), a melody plays (Bach, I’m almost positive). Really, there are four melodies (all four by Bach, I think): to go from one to another, you just have to squeeze the creature’s head.

There is much to be said about the octopus’s tentacles, with their matching, somewhat indecipherable images embroidered in eight different colors. When you press them, a surprisingly feminine voice recites the names of those colors. Eventually, after mashing each tentacle hundreds of times, my son will be able to name those colors in Spanish, and in French, and in English as well, because a switch located on the mollusk’s head allows the eight-colored octopus to also express itself in those languages.

Following is a brief description of the Spanish-speaking female voice:

- ¡Azul! (Blue!) The octopus’s voice pronounces the word with enthusiasm, subtlety, and just a smidgen of surprise, as if it had forgotten the name of the color and was remembering it only now. I should also mention that the sound of the z (pronounced like the s in sea) leads one to believe this is a Latin American octopus we’re dealing with—no Iberian lisp here.

- ¡Verde! (Green!) There is enthusiasm in the invertebrate’s voice, but also impertinence, as if it needed to clarify that we are talking about that specific color and no other. The labiodental pronunciation of the v comes off as a bit ridiculous, given that, as the Royal Spanish Academy has indicated in various documents, “in Spanish there is no difference at all between the pronunciation of the b and v.”

- ¡Amarillo! (Yellow!) I’m really not sure if there is tenderness on the part of the octopus when it pronounces this word. The voice sounds forced, inauthentic, mechanical.

- ¡Marrón! (Brown!) At this word, the octopus’s voice becomes unexpectedly sensual. Anyway, as far as I know, here in Latin America we call this color café and not marrón. The peninsular Spanish is cause for confusion, considering the aforementioned z in azul. Could this perhaps be an octopus from the Canary Islands, in Andalusia?

- ¡Blanco! (White!) The bilabial sound is overly marked, probably to contrast with the (absurd) labiodental sound of the v in verde. I’d have to say there’s an unpleasant, slightly ominous shading to the voice here.

- ¡Rojo! (Red!) The pronunciation is funny, as if the cephalopod were hesitating, as if it were guessing at rather than stating the color’s name.

- ¡Morado! (Purple!) I’d call this pronunciation fairly neutral, perhaps just slightly wonderstruck.

- ¡Anaranjado! (Orange!) Inexplicably, on reaching the orange tentacle, the voice that emerges is another person’s charmless vocalization. Let me be clear (it’s hard for me to understand this, and thus to explain it): the eight tentacles of the octopus are associated with eight different colors, seven of which are voiced by a certain or uncertain female speaker (let’s call her, in honor of the aunt who gave us the octopus, Margarita), but when you press the leg that corresponds to orange, or naranja, or anaranjado, or whatever you want to call this controversial color, there is a different voice, which does not transmit any enthusiasm and, on top of that, is clearly foreign (let’s call its owner Barbara). “Anarrranhadou,” says Barbara, unable to camouflage her problematic pronunciation of the r and of the vowel o.

I have no choice but to open, with utmost caution, the back of the octopus’s head and switch the critter’s language. All eight colors in English are recited by the voice of another woman, whose name is Margaret, and the same happens in French with the elegant Marguerite. The voices of Margarita, Margaret, and Marguerite are manifestly different and correspond to native speakers of, respectively, Spanish, English, and French. And of course neither Margaret nor Marguerite is responsible for the irritating voice of Barbara.

What follows is my idea of what happened. That morning, Margarita got to the studio early and happily recited her eight colors; since she didn’t have plans for the rest of the day, she decided to wait around for Margaret and Marguerite, because they’re all friends. I don’t know what language they communicate in, but I’m almost entirely sure they are friends or at least friendly, even loyal, colleagues. Margaret said her lines or her words—her eight one-word lines—and then it was Marguerite’s turn, and then the three of them left and disappeared into the streets of Beijing or Shanghai (if we go by the tag on the octopus, Baby Einstein brand, all of this is taking place in China) in search of a café where they could sit down and gossip. And then someone at the production company listened to Margarita’s recording and realized that instead of anaranjado, as was the plan, she had said naranja, and this struck the producer as a terribly serious problem. He called Margarita right away, but Margarita’s cell phone was out of batteries, and it didn’t even occur to this producer to contact Margaret or Marguerite, as he didn’t think they were friends (he found the very idea of friendship a bit nebulous). The entire staff of the production company threw itself into a desperate search for some native Spanish speaker, but there didn’t seem to be anyone in all the immensity of China who was capable of pronouncing anaranjado naturally. The best they could find was a willing and helpful announcer, who ended up ruining everything, but of course this isn’t Barbara’s fault. How unfair, how cowardly it would be to blame Barbara.

Determined to forget the ear-splitting asymmetry, I put my little chilpayate into the baby sling and go out for a walk. I feel him settle in against my chest and fall asleep. At the grocery store I buy four jicama roots and five mamey fruits, and I think about how Mexico City, where I live now, is four thousand–plus miles away from my country, and how in Chile there is no jicama or mamey, and how my chilpayate would be called a guagua there. How terrible I would find it, now, to live in a country with no jicama or mamey.

Then I’m back home, in the rocking chair. The baby is still sleeping on my chest. He has a cold, and he’s emitting the funniest little mini-snores. My wife is stretching on the rug; her back hurts. “What color is the mamey fruit?” I ask her. “Mamay-colored,” she replies. The baby squirms on my chest, restless, about to wake up.

Jazmina picks up a novel and lies down on the sofa, and as she does she accidentally—I presume—sets off the octopus, which plays one of its melodies. She turns it off and puts it aside. I identify with that octopus, I think. With its impaired orange tentacle. That’s what I am to my son, I think, with healthy, happy dramatics: a tentacle that talks a little strangely, a foreign leg. Just then the boy wakes up and looks at me sleepily but smiling, as though saying to me: Anarrranhadou.

—Translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell