The whole of the thought

In 1998, Maverick Records engaged a market-research company to collaborate on a promotional plan for Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie, the highly anticipated sophomore album from Alanis Morissette. “Because of the nature of the business, we knew that Alanis had earned a ‘Free Pass’ from radio and MTV,” the researchers wrote—“her first song would get massive airplay no matter what it was.” After that, they offered several possible fates, including a “doomsday scenario” in which no songs beyond that first single received significant airplay. In this disturbing outcome, they projected three million in sales—a fine yield for a mortal, but disastrous for a superstar whose previous record had sold over thirty million copies.

“Sadly,” the researchers reported, “we were dead on with this projection.” Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie quickly became a consummate example of the sophomore jinx, a slump from which Morissette’s career has yet to recover. When she sings, on one of the album’s underperforming later singles, that whenever she thinks of the early ’90s, an ex-boyfriend’s “face comes up with a vengeance, like it was yesterday,” she seems to be eerily forecasting present attitudes toward herself.

That song, “Unsent,” invites one of the only linear readings on a long and rambling record that is otherwise a mess. After Jagged Little Pill, a taut commercial juggernaut of an international debut, what could account for a follow-up so odd? For starters, its creator had already endured a doomsday scenario of a different sort: Jagged Little Pill’s success had been woozy, steep, and quick; a tour that began at tiny rock venues concluded, eighteen months later, in sold-out stadiums where crowd-control personnel were forced to request that fans “surf the internet, not the Morissette.” This is a lot for a twenty-one-year-old to deal with.

In the wake of this ambush of success, Morissette took two friends and three relatives on a six-week trip to India, with hopes of dealing with events that should have, as she would sing later, delivered her to “a far-gone asylum.” The purpose of her trip was a sequence of soul-based inquiries, and Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie constitutes her own research report.

There are more-obvious ways to organize the findings of the heart, but Morissette favors the inventory, the lawyerly catalog. “Thank U,” that free-pass first single, works entirely in this mode, with a chorus that thanks, in order of credit: India, terror, disillusionment, frailty, consequence, silence, providence, nothingness, and clarity. The verses offer suggestions, still in list form: “How ’bout no longer being masochistic? How ’bout remembering your divinity? How ’bout unabashedly bawling your eyes out? How ’bout not equating death with stopping?” The advice is delivered amiably and the suggestions are strong, but—it must be said—there are an awful lot of them.

Yet the “must be said” is precisely the driving force behind these lyrics, many of which sound less streamed from Morissette’s consciousness than dredged up, still snarling, from the thick muck at its core. On the B-side “These R the Thoughts,” Morissette sets the brief: “These are the thoughts that go through my head in my backyard on a Sunday afternoon when I have the house to myself and I am not expending all that energy on fighting with my boyfriend.” Plain enough, and the first item clearly follows on: “Is he the one that I will marry?” By item three, it’s getting weird: “Why do I feel cellularly alone?” At item five— “Can blindly continued fear-induced regurgitated life-denying tradition be overcome?”—the connection to consensus reality has vamoosed.

Under its nested title—Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie, qualified, modified, and undercut—the whole album does what it threatens to do on the box: it attempts to represent the self as comprehensively as possible, a modernist gambit to capture the whole of the thought. This positions it against the ideal aims of the pop song, which is truest when imposing order on the chaotic heart. In most pop, you may thank either clarity or nothingness, but not both. Most successful pop is a distillation.

But there are other genres with different priorities, such as the diary, which may privilege breadth or reach or thoroughness—even messiness— over order. In polite company, that is, or in a Top 40 song, it is either rude or baffling to minutely explore a half remembered conversation, an acquaintance’s need for therapy, or one’s own inability to seek happiness from an appropriate source. But neither rudeness nor bafflement is a concern for the diarist, who is at once the text’s narrator and its first addressee.

Even if we view all diaries as semipublic works, as Susan Sontag did, our awareness of their personal roots is part of the bundle. Some documents can be fully read or heard only when the reader or listener is in full knowledge that they are, in some real and early sense, private. Their privacy, their inwardness, must be part of the work; so must our own ostensible absence from it. Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie is a disorderly document, and it may seem a lot for Morissette to ask that we sort it out for ourselves. Then again, she may or may not be asking us anything.

Ronnie Scott

Twilight is a mask factory

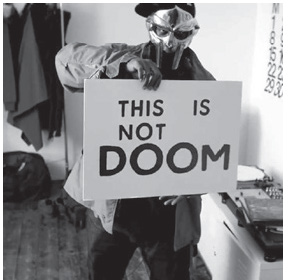

On the night of February 25, 2010, a mob of hip-hop fans huddled in Toronto’s Kool Haus, shouting, “It’s not him” and “Get the fuck off the fucking stage.” The subject of their ire was the mercurial Daniel Dumile, better known as MF Doom, the spastic, in ventive rapper who has, since 1999, concealed his face behind a metallic gladiator mask. (Dumile has also created additional rap characters, including Zev Love X, Viktor Vaughn, and King Geedorah.) Onstage, a man of approximately equal size to Dumile made vague rap gestures—gesticulating hands; nodding head; slow, rhythmic stroll—but rarely let the mic leave his mouth, even for ad libs. For a rapper who’s supposed to be garrulous and crude, the tight-lipped dude hardly seemed to be keeping it real.

There had already been a spate of incidents like this one. Dumile’s reliability, which has been called into question regularly, was disputed most aggressively between 2007 and 2012, owing to his use of performing standins, known variously as “Doomposters” or “MF Dupes.” In a 2009 interview with Ta-Nehisi Coates in the New Yorker, Dumile, who has alternately denied and affirmed the yarns spun by conspiracy theorists, ascribed a theatricality to the stunts: “I’m the writer, I’m the director. If I was to go out there without the mask on, they’d be like, ‘Who the fuck is this?’”

The story of Black Bastards, the sophomore effort from KMD, Dumile’s pre–MF Doom rap group, might shed some light on that question. Planned for release in 1994, the album was allegedly shelved by Elektra Records for its seditious cover illustration: a Sambo figure hanging from a gallows, the album’s title spelled out as a game of hangman: BL_CK B_ST_- RDS. Scoffing at the label’s reluctance to release the album, rock critic Robert Christgau urged readers to “make a face at Elektra.”

In tandem with Dumile’s own ecstatic imagination, the music industry’s early ambivalence toward Black Bastards may be why he makes all of his faces: to reclaim ownership of his career, his narrative. “…if there’s going to be a first impression I might as well use it to control the story,” he told Coates. “So why not do something like throw a mask on?”

Indeed, why not? This is the same man who says, as his alter-ego Viktor Vaughn, “Dub it off your man, don’t spend that ten bucks. / I did it for the advance, the back end sucks.” When Dumile jokes in the New Yorker interview about sending “a white dude” and “Chinese niggers” to perform as MF Doom, it’s hard not to read in his antics a rebuke against both the trappings of the music industry and the strict, if understandable, expectations of fans who think they have him figured out. Dumile embraces not only his provocateur status but also the racial coding behind it; on the Vaughn album Vaudeville Villain, he calls himself a “shuck-n-jiver.”

According to Valerie Cassel Oliver, editor of Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art, black performance art is “rooted in spectacle and… occupies the liminal space between black eccentricity and bodacious behavior, between political protest and social criticism.” To wit, Adrian Piper’s 1973 piece The Mythic Being navigates physicality and disintegration by creating, in the words of Naomi Beckwith, “a live character in the public realm and… a visual representation in drawings and advertisements.” David Hammons’s 1983 Bliz-aard Ball Sale, for which the artist vended snowballs on a street corner, critiques the art world’s high capitalism. William Pope. L’s The Great White Way, begun in 2001, was an intermittent nine-year, twenty-two-mile crawl up Manhattan’s Broadway in a Superman costume. The late interdisciplinary artist Rammellzee often materialized in public masked as one of twenty-two characters he’d created. In the context of this lineage, Dumile’s antics lay bare his desire to commodify his own artistry by simultaneously selling spectacle and appearing nowhere.

The reissue of Black Bastards, released for Record Store Day in 2015 on Dumile’s own label, Metal Face Records, is housed in a pop-up board book, recalling not the iconic Little Golden Books series so much as The Story of Little Black Sambo, Helen Bannerman’s controversial 1899 book whose titular character has become a murky relic of the Jim Crow era’s “darky iconography.” The Sambo figure’s face recurs throughout the book with an anti-sign superimposed on it. (The cover’s “hangman” pun is typical Dumile, as it should be—its illustrator is The Emef, yet another of his personas.)

The book also includes a picture of Dumile as Zev Love X, one of his only self-released unconcealed photos in recent memory. It’s fitting, in a sense, that his reinvention of Black Bastards as memoir comes as he continues to distance himself from the conventions of performing (at a recent festival, he literally phoned in a pre-recorded routine). It helps us appreciate his two-step between seriously evoking racialized characterizations of performing black people and flippantly alluding to his PR stunts; between the authenticity expected of a singular author and the honesty afforded by multiplicity; and between real-life eccentric and mythic being.

On “Biochemical Equation,” a 2005 track with RZA of the Wu-Tang Clan, MF Doom wonders:

He wear his beard like a frizzyhaired grizzly

And kept his appearances exquisitely rare—where is he?

Is he in your backyard or on your front porch,

Or standing in the corner of the club with the blunt torched?

Kool Haus patrons probably had similar questions that confusing February night. MF Doom eventually turned up at the club, emerging to perform “Accordion,” a popular cut by Madvillain, his collaboration with the producer Madlib. The audience put on their happy faces.

Niela Orr

I don’t go for movie stars

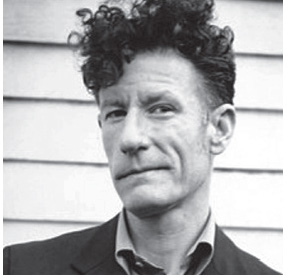

I n the spring of 1992, Lyle Lovett, then on the public radar as an odd-looking crooner of quirky country music, released his fourth LP, Joshua Judges Ruth. It’s an extraordinary album: while Lovett had previously crafted a body of songs that were wry, salty, surreal, goofy, sinister, and sad, every track on Joshua possesses several of these qualities at once. The patient, spacious arrangements evoke an astonishing range of the musical heritage of Lovett’s native East Texas—country, folk, blues, rock, gospel, boogiewoogie, even jazz and ranchera by way of Western swing—as well as the fraught interracial history from which that heritage proceeds. It’s also an album of mature concerns—featuring three songs about death in a row—on which Lovett refers to his family and his upbringing with uncharacteristic candor. Joshua’s quiet confidence seemed to sneak up on many listeners; respect for it deepened in the months following its release, and anticipation grew regarding what Lovett would do next.

What Lovett did next, in the summer of 1993, was meet Julia Roberts, then on the public radar as the biggest female film star in the world and a favorite topic for scandal sheets owing to her short-lived romances with strapping A-minus-list leading men. Within a few weeks, Lovett and Roberts were married, and overnight the follow-up to Joshua Judges Ruth became a subject of interest not only to a relatively small group of Lovett admirers but also to millions of supermarket-tabloid browsers, clamoring for clues about the least likely celebrity pairing since Christie Brinkley and Billy Joel.

For Lovett, this turn of events presented—among many other things, to be sure—a rhetorical challenge: how to advance his established project as a songwriter and performer in the fresh glare of massive public attention? How to jointly address his new and old audiences in a manner that was genuine, courteous, and controlled?

He submitted an answer in the fall of 1994, in the form of his fifth LP, I Love Everybody. It consists of eighteen songs, all of which Lovett had written in the 1970s and early ’80s— before he recorded his first album, and long before he crossed paths with his new bride. But it’s not a compendium of B-sides and rarities, nor does it contain new versions of previously released material: just fresh studio recordings of some of Lovett’s earliest songs, all unknown to almost everyone except friends, family, and the habitués of the coffeehouses and dance halls where he’d launched his career. Songs so old, that is, that they might as well have been new.

Naturally, then, upon its release, I Love Everybody registered as a personal record. But it’s also a reticent one, speaking eloquently about where Lovett came from while remaining mischievously tightlipped about his present circumstances. From its title— surely too amiable not to be sarcastic— to the drumroll that ends its final track, the album is a study in layered ironies; as such, it enabled Lovett to continue his measured disclosures to sympathetic fans while simultaneously introducing himself, on his own terms, to a nation of curious onlookers. Best of all, it deftly deflected the perfunctory prying of those who approached the album seeking only coal for the gossip furnace: since all of the songs were at least eight years old, they couldn’t possibly be about marrying Julia Roberts.

Except they kind of were. Lovett might have written the material long before, but he’d selected and recorded it recently, and the album abounds with winking references to recent events. The narrator of “They Don’t Like Me,” for instance, bemoans his disapproving new in-laws (“He’s really not that ugly, dear; / she could’ve done much worse”). This can’t have been more than a comic trifle when originally composed, but brought out of retirement on I Love Everybody, it turned into a secure space for Lovett to acknowledge public skepticism regarding his marriage. The fact that the song as written couldn’t possibly acknowledge it is, of course, what makes the space secure.

Occasionally Lovett applies these methods to even subtler ends. “I don’t go for fancy cars,” he sings at the opening of the album’s centerpiece, “for diamond rings / or movie stars. / I go for penguins.” He sings “movie stars” with a smooth, jazzy rubato that doubles as the See what I did there? of a practiced vaudevillian: clearly he does go for movie stars, even if the narrator of “Penguins” doesn’t. By dusting off this old song—originally a character sketch of an acquaintance with an extensive collection of toy penguins—he suggests that he’s more surprised than anyone to learn this about himself.

But the suggestion gets trickier as the song proceeds and Lovett’s identification with the speaker deepens. “Throw your money out the door. / We’ll just sit around and watch it snow”—those lines rhyme in East Texas—“I go for penguins. / Oh lord, I go for penguins. / Penguins are so sensitive / to my needs.” Aside from repetitions, of which there are many, these are the lyrics in their entirety. Lovett sings them over a funk drumbeat, accompanied by upright bass, horns, and backing vocalists, but no piano or guitar to lend harmonic cues about the song’s emotional direction. Without them the song seems full of holes, constantly on the verge of getting started in earnest, right up until the moment it comes to a halt. It leaves us aware of everything it declines to do: to explain its odd assertions of value, even to admit that an explanation might be necessary.

Music derives meaning not only from what it says and how, but also from the contexts in which it’s encountered: a song we liked in high school becomes the first dance at our wedding or that song from that commercial. Yet artists rarely get the opportunity to perform this kind of recontextualization themselves, with work that was theirs to begin with. Lovett plays this game throughout I Love Everybody, employing curation over composition, working like a collagist of his own past to tell the story of his marriage by pointedly not telling it. He and Roberts separated in 1995, and divorced not long after. He still performs “Penguins” at concerts, but he no longer sings the line “or movie stars.” Instead, he hums through it: yet another audible, eloquent erasure.

Martin Seay

Please believe me

Writing music and writing fiction require mostly different skills to reach mostly similar ends. Both reach for a kind of enchantment. The purposes of that enchantment vary widely (satiric, didactic, aesthetic—what the hell, oneiric), but in order to achieve the desired effect, the artist will often pretend there’s some autobiographical content on display— and then deny it when pressed. You do this because people want your songs and books to be “true,” or “honest,” or “authentic.”

Because metaphor is a ladder to the truth and not the truth itself, and art (at least good art) is built from metaphor, all art is necessarily a lie, an imitation, a parody. But it’s good business to become the thing people want you to become, which is invariably yourself. This presents an insoluble problem, though, because the self is always a construct. There is very little of me in the me of my songs or novels or scripts or occasional forays into journalism. When I do use incidents from my own life in a story or song or script or essay, I twist them into a Gordian knot of fiction that no sword could cleave.

Other writers, I’m sure, work differently. They are all wrong.

When I played in Guided By Voices, fans often approached Robert Pollard (a notoriously opaque lyricist) with suggestions to “improve” this or that line from one of his songs. He was good-natured about it, but genuinely puzzled. “When they make an album, they can make the words mean what they want,” he would say.

But most rock lyrics are impressionistic doggerel buttressed by the emotional heft of the music; calling a songwriter an unreliable narrator is like calling the sky blue. The songwriter’s job is to be an unreliable narrator, because a song is a mirror, not a picture. It reflects the listener’s emotions, not the songwriter’s intentions. Even the most nakedly vulnerable song ends up as the soundtrack to someone else’s heartbreak, and whether or not it reflects the writer’s actual experience, or even his or her imagination, should be irrelevant. We want the song to be real.

My first novel, Artificial Light, had a prominent character called Kurt C. He bore little relation to Kurt Cobain, though most readers naturally assumed a connection, which was very much intended. The Kurt in my book lived in Dayton, Ohio, was no longer a musician, and did not kill himself. I was trying very loosely to reboot the myth of Samson as a kind of sun-god metaphor, so I needed a Christ figure. I used a few actual aspects of Cobain’s personality and grafted them onto an update of Dostoevsky’s Prince Myshkin. (Similarly, the Orville Wright in Artificial Light is not the Orville Wright who co-invented the airplane, though he shares some character traits and biographical facts with his namesake.) Both Kurt and Orville were excellent liars, of course. Just like Jesus.

As far back as I can remember, even when committing acts of journalism, I could not, for the life of me, tell the truth. At least not as “myself.” The persona I assumed when writing about rock music, essentially a musically illiterate, alcoholic asshole, bore no relation to my “real” personality. (OK, maybe some relation.) But because I’ve always been morbidly shy and borderline agoraphobic, I constructed a shell by gluing together bits of other people’s personalities and used it to disconnect myself from the prolix opinions of my rock critic alter ego, which, for all I knew, were either courting outrage or not being read at all.

In the pre-internet era it was easy to believe that what you were writing was evanescent, immaterial, unimportant—because it was. But now technology has purportedly removed all barriers to information and access—the only currency rock critics ever had in the first place— and intense, voluminous, often angry communication from fan to artist is easier than ever, which both delights and scares the hell out of the latter. Without a mediating presence, your opinions—you—quickly become anodyne and boring.

Fortunately, it’s also easier than ever to construct a personality rather than present your true self, which, again, doesn’t exist anyway. So that’s what we do, only now we call it curating, and pretend it means something, because—and this will never not be true—we, as a species, love pretending more than anything. It’s the first thing we learn how to do. Trust me on this one: the most unreliable narrator is always you.

James Greer

NON-EXHAUSTIVE LIST OF VERIFIABLY FALSE SONG TITLES

“My Name Is Robert,” Dan Deacon

“My Name Is Trouble,” Keren Ann

“My Name Is Jonas,” Weezer

“You Can Call Me Al,” Paul Simon

“My Name Is Mud,” Primus

“I Am Fred Astaire,” Taking Back Sunday

“Me Lene Popi” (My Name Is Popie), George Dalaras and Goran Bregović

“They Call Me Country,” Jamey Johnson

“I Am John,” Loney, Dear

“Call Me Lightning,” Joan Jett

“I’m Paris Hilton,” Lil B

“They Call Me Cadillac,” Randy Houser

“My Name Is Despair,” the Charlatans

“My Name Is Earl (I Want a Girl),” Gerry & the Joy Band

“My Name Is Jing Pow Ki Poo Just Like That Other Guy,” Monotrona

“I’m Jim Morrison, I’m Dead,” Mogwai

“Call Me Rambo,” Ackie

“My Name Is Carnival,” Jackson C. Frank

“My Name Is Jack,” John Simon

“I’m a Truck,” Red Simpson

“My Name Is Love,” Rob Dickinson

“Call Me the Breeze,” J. J. Cale

“I’m a Wheel,” Wilco

“I Am a Rock,” Simon & Garfunkel

“I Am a Tree,” Guided By Voices

—list compiled by JW McCormack