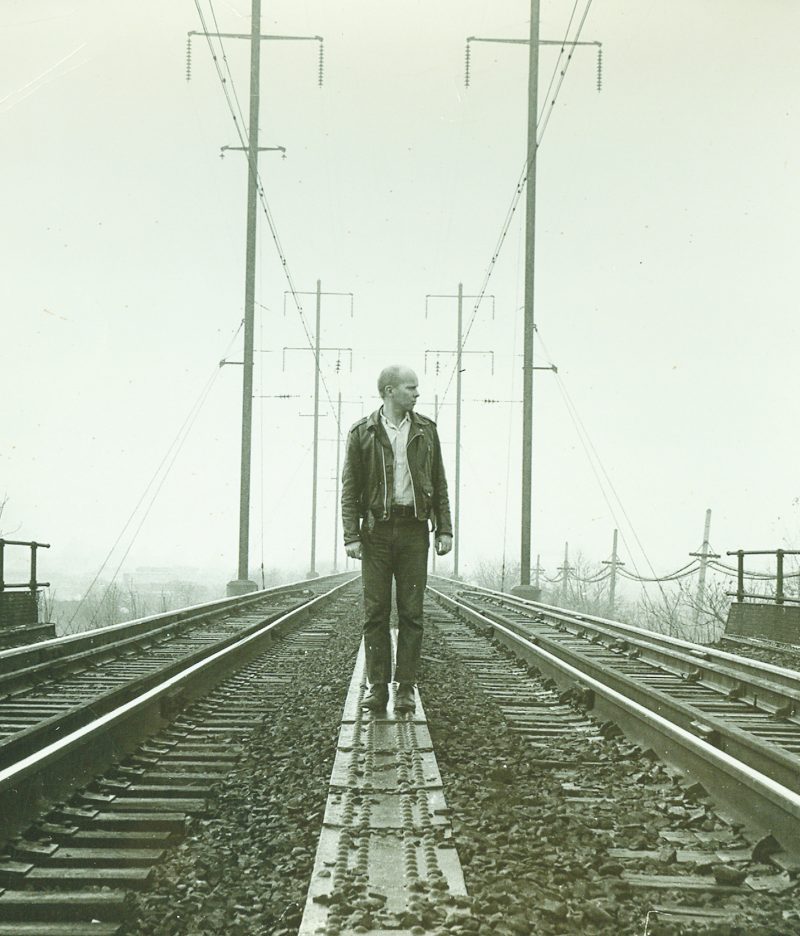

“With Ray, he made it very clear to me from our meeting, in the autumn of 1956, that I wasn’t supposed to ask about the past,” says William Wilson of mail artist Ray Johnson. Wilson kept this tacit promise over decades of close friendship, during which Johnson—who rarely mentioned his own family—came to Christmas dinners, celebrated the birthdays of Wilson’s twin daughters, and became close friends with Wilson’s mom, feminist assemblage artist May Wilson.

The few stories Wilson does know about Johnson’s Depression-era childhood in Detroit appeared unexpectedly in conversation, prompted by a song they were listening to, or a book Wilson was talking about, or something a friend had just said or done. One such story involved an afternoon in a rowboat with a friend, during which, according to Wilson, Johnson made “an erotic error.” This is all Wilson knows about the incident, because “if he told about the past, I was not allowed follow-up questions.” As close to Johnson as anyone ever was, Wilson still had to deduce the meanings and implications of such stories for himself—a dynamic that led to a lifelong study of his friend. Wilson’s collection of Johnson’s artwork is large, and his writing on Johnson is prolific. Regarding the “erotic error,” Wilson theorizes that the rebuilding of that friendship (following what is assumed to be a failed sexual advance) influenced Johnson’s art by teaching him “about construction as bringing forth something for which we have no prior rules.” It may also have taught him that intimacy required concealing aspects of his identity, even from his closest companions.

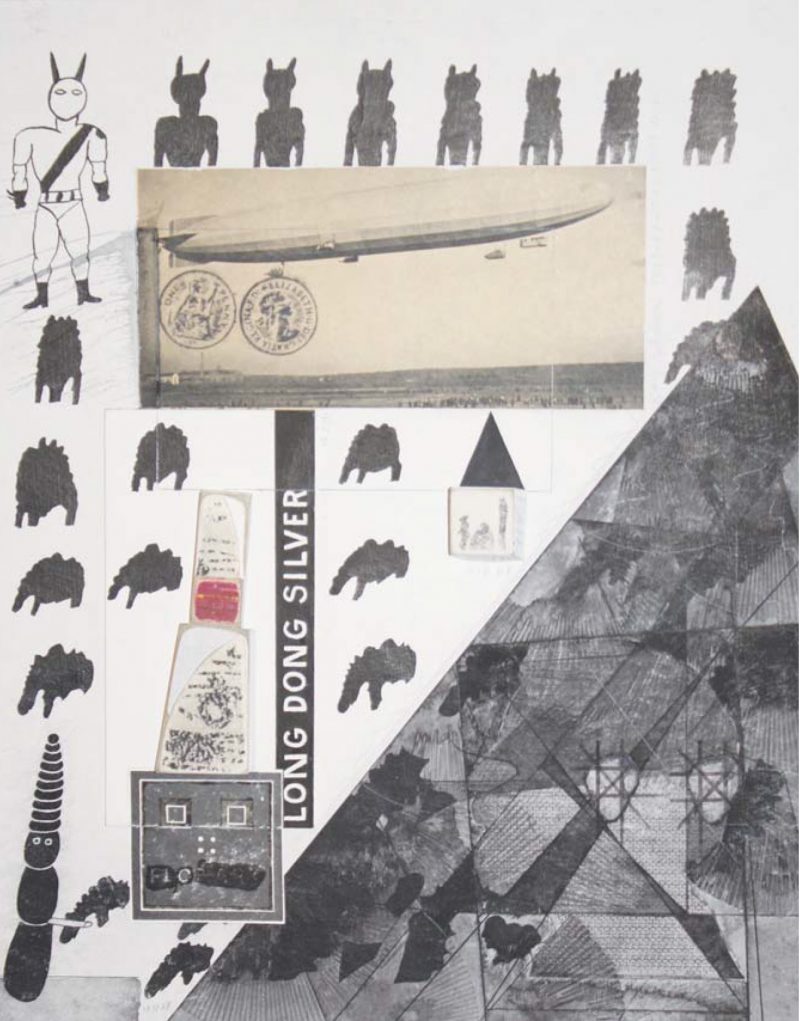

Johnson revealed more of himself, albeit obliquely, in his collages (called “moticos”) and his letters, sent regularly to everyone on his lengthy mailing list. “It would be very hard for me to separate him as a person from his work,” said sculptor Richard Lippold, who met Johnson at Black Mountain College, a former art school in North Carolina. In 1948, Lippold moved to Black Mountain—where Johnson was studying under Josef Albers—for a professorship, bringing along his young wife, a dancer named Louise Greuel (for whom John Cage would compose “Music for Piano 2”).

Richard Lippold and Johnson quickly began an affair, which then became a relationship, and they continued to see each other until 1974, long after all parties involved had moved to New York. “It’s very hard for me to say,” said Lippold about his partner of twenty-six years, “but who was this man? He kept so much of himself to himself… his whole life was a kind of game, like...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in