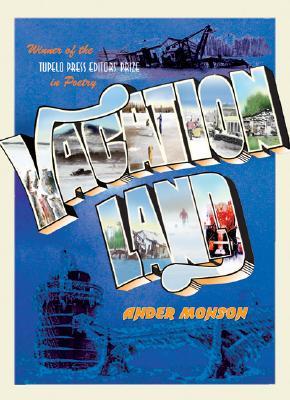

Ander Monson grew up in remote, grim northern Michigan and (if we trust the poems) lost at least two of his closest friends before they had finished high school. Or, if you prefer: Ander Monson has breathed life into a fictive northern Michigan townscape where two teenagers have died in an auto accident before finishing high school, and a third narrates poems about them. The loss of Jesse, a childhood friend and partner in misdemeanors, and “Liz, my X, my axe to break the freeze” dominate the book, which consists mostly of careening, bristly laments for them and for the half-gutted mining and forestry towns whose ghostly half-lives as resorts provide the book’s title: “This is my vacationland, my very own / Misery Bay, my dredge, my lighthouses, my vanishing / animal tracks in snow.” In Monson’s northern Michigan, death is just “the other Canada.” As for the survivors, “We are what is left. We drift. / I guess this is a sort of manifesto.”

This manifesto encompasses plenty of complaint—there’s not enough money and not enough to do. Monson kicks against “awful playlists and shitty DJs” on album-rock radio and “coin-op beds that vibrate in the Budget Inn.” But the poems also celebrate defiant excess. In this land of scarcity, right living involves using up what you have, whenever you have it; otherwise someone might wreck, steal, or use it and you might not get any more. This rule applies to parties, trucks, and emotional commitments—a carpe diem for obscure doomed youth. Monson’s elegies stack up realist-novel (or even YA) detail, but their method of stacking shows an exuberant anger and a comfort in disconnection that marks the poems as contemporary. Uncommitted to storylines, the speaker lets language go where it will, even when it leaves him out on the ice.

Vacationland teems with self-conscious forms (sonnets, lists, outlines, “self-portraits”) and eye-catching titles (“Big Fungus Elegy for X as Meteor”). Monson runs the slightly gimmicky online journal Diagram, and some of his forms are (attractive) gimmicks, too:“Index:A” records the disorienting life of an amputee through entries such as “Abandonment, by the father, the mother, the family,” “Above-knee peg leg,” and “Acceptance of help.” His best poems work less like diagrams and more like rants, rolling the details of particular, unsalvageable lives into versions of grief as general (or as American) as the rock anthems these kids love.

If that description makes the book sound limited, don’t worry. It is no more so than the first five Bruce Springsteen albums. Sentences as complex as the Boss’s arrangements imply that blue-collar and teen-colloquial lingos carry an outlook wholly compatible with Romantic hopes. The last elegy begins “Liz your party is a wreck,” and ends by praying for “the reinstatement / of the temporary privileges of the heart.”

Monson’s first book of poems serves as a companion to his prose debut, Other Electricities, which follows the same characters through some of the same events. The play between lyric sincerity in the poems—as if all describe the poet’s life—and apparent invention in the stories—as if none had a basis in fact—is an added virtue, though never merely a game. Readers of poetry ought to care not whether Jesse and Liz have genuine tombstones but whether these elegies cause us to mourn them. Monson has intelligence to spare, but no reserve and no decorum—all have been thrown off the bridge, lost under the car-exhaust-tinged snow.