This is the first of three pieces in which I’ll be interviewing thinkers working on issues of justice, solitary confinement, and incarceration. Over the next several months, I’ll talk with Lisa Guenther about what solitary confinement does to bodies and minds, and to Linda Ross Meyer about what might happen if we start talking about justice in terms of mercy rather than retribution.

In this issue, I speak with Colin Dayan about how, in courts and prisons in the U.S., focus has shifted from prisoners’ rights to questions of how best to keep a prison system running. In that move, we have lost sight of the human individual. Dayan is Robert Penn Warren Professor of the Humanities at Vanderbilt University, recipient of Guggenheim and Danforth fellowships, an elected member of the Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the author of The Law Is a White Dog: How Legal Rituals Make and Unmake Persons.

—Jill Stauffer

THE BELIEVER: In The Law Is a White Dog you show both that solitary confinement in supermax units—special control units within some prisons—destroys the personhood of prisoners, and that U.S. courts have used legal language to sanitize the practice and render it permissible. Let’s start by getting a sense of what is so damaging about these supermax units.

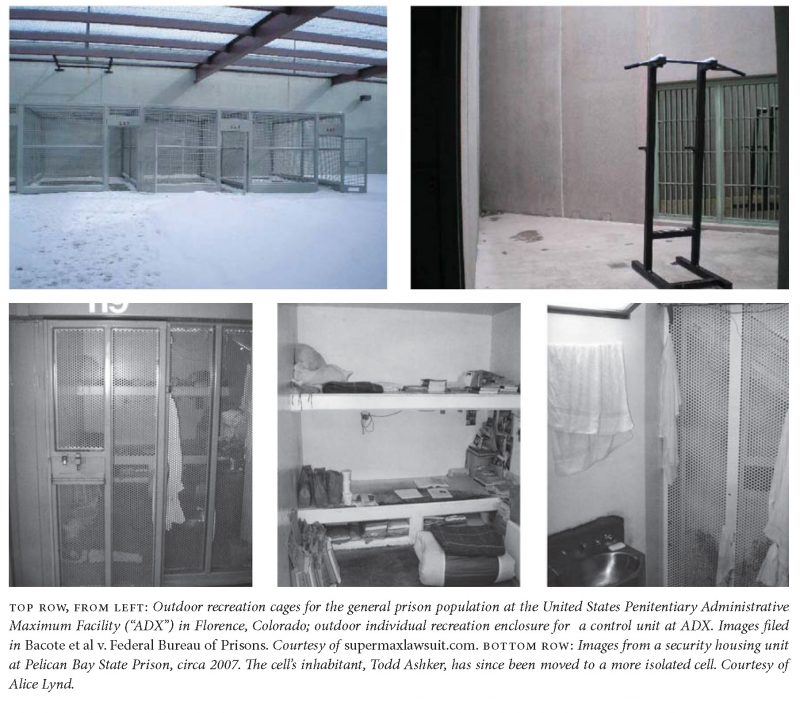

COLIN DAYAN: The isolation is unremitting. Prisoners are locked alone in their cells for twenty-three hours a day. Their food is delivered through a slot in the door of their eighty-square-foot cell. They stare at unpainted concrete walls onto which nothing can be put. Except for the occasional touch of a guard’s hand as they are handcuffed and chained when they leave their cells, they have no contact with another human being. Inmates have described life in the massive, windowless supermax as akin to “living in a tomb,” “circling in space,” or “being freeze-dried.” Some are held in these conditions for years or decades.

BLVR: No reading materials, no possessions, no art on the walls, no letters or phone calls from the outside world. If to be in the world is to be with others, then when you take from a person everything that links him to the human world, you refuse him human status. Or: to be without others is to lose the world. To me that sounds like an excess cruelty that we don’t associate with legal practices in modern democracies.

CD: I know. Basically, alongside the death penalty, we have invented a new form of death—a death-in-life that needs no judicial decision and is not open to scrutiny. Basic human needs—food, clothing, shelter: the constitutional minima—are met, but the risk of mental trauma and psychological decompensation is high. These destructive effects have long been recognized, not just by Alexis de Tocqueville and Charles Dickens. The sensory deprivations of the supermax have been repeatedly condemned since the 1980s by the United Nations Committee Against Torture, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Center for Constitutional Rights. In June of 2012, Senator Dick Durbin and the Senate Judiciary Committee began an unprecedented review of solitary confinement.

BLVR: So why isn’t this what the eighth amendment to the U.S. Constitution would call “cruel and unusual”?

CD: One of my most far-reaching claims is that “modern” forms of punishment, such as supermax confinement, are every bit as barbaric as such obviously horrific practices as disemboweling or drawing and quartering.

BLVR: So you’re suggesting that, even if we think we have progressed to an enlightened standard of human decency, we have not.

CD: Right. When I spent two years visiting supermax facilities in Arizona, I found to my surprise that what I had written about slavery in my Haiti book—the mechanisms of denigration, abuse, and torture—were not stories of a distant past. I found that what had existed in the Black Code [laws concerning the discipline and control of slaves in the French colonies] was being realized in the daily practices of prisons in the United States.

BLVR: The past haunts the present. We just use nice words in our legal briefs and keep the torture facilities clean and well lit.

CD: Yup. In fact, I argue that this radical dehumanization of prisoners is made possible by such legal formulae as “evolving standards of decency.” The unspeakable might well become possible wherever the legal or literal promise of humanitarian punishment is made.

BLVR: What do you mean?

CD: These units are clean and new, powered by cutting-edge technology and design. But just because these units aren’t like “the hole” popularized in movies like Murder in the First or The Shawshank Redemption doesn’t render them humane. If the prohibitions of the 1689 English Bill of Rights are conjured as a backdrop—disemboweling, decapitation, and drawing and quartering—then the ban on cruel and unusual punishments might well seem obsolete. It is aimed only at “barbarities” that have long since passed away. But cruelty takes many forms, and excessive harm can be redefined in terms that put it outside the precincts of punishment, making it increasingly difficult to prove an Eighth Amendment violation.

BLVR: How so?

CD: In the book, I wanted to demonstrate how rituals of law tread in realms that are outside the precincts of reason. Just as slave law relied on fictions of invisible taint, blood curse, and persons as things, I argue that legal thought today still traffics in the irrational. If I had to boil down the gist of this book to just a few words, I would say that the law deals in what we think of as the supernatural: creating creatures who are alive in fact but dead in law.

BLVR: Say more.

CD: Here is an example of what I call “the sorcery of law.” The main character is Justice Scalia, and the case is Wilson v. Seiter, in 1991. It changed and limited the Court’s intervention in horrific conditions of confinement. Here, the language of the law and the rationale invoked ensure that abuses and arbitrary actions can be masked by vague standards and apparent legitimacy. In Wilson, Scalia focused on the meaning and extent of punishment. He returned to Judge Richard Posner’s ritual of definition in Duckworth v. Franzen (1985): “a deliberate act intended to chastise or deter.” So the Supreme Court required not only an objective component (“Was the deprivation sufficiently serious?”) but also a subjective component for all Eighth Amendment challenges to prison practices and policies. The Court decided that if deprivations are not a part of the prisoner’s sentence—delivered by the sentencing judge—then they are not really punishment unless caused by prison officials with “a sufficiently culpable state of mind.”

BLVR: Wait. You’re saying that the subjective component that matters here—in cases about prison cruelty— is not the prisoner’s experience but the state of mind of the alleged abuser? What matters is whether a guard or warden intended harm rather than whether the prisoner is harmed?

CD: Exactly. No matter how much actual suffering is experienced by a prisoner, if you can’t establish that harm was intended, then the effect of that harm on the prisoner is not a matter for judicial review.

BLVR: And that’s a Supreme Court decision.

CD: Yes. Obvious signs of violence disappear in quest of the unseen. What was the official thinking? Was he “deliberately indifferent”? Did he have a “sufficiently culpable state of mind”? If we follow the logic of this case, all agency is transferred to the person of the government official, while the mind—through the defining strategies of legal reasoning—is literally sucked out of the prisoner.

BLVR: This is one way law has the power to make or unmake a person—by deciding whose words and whose bodily harm can be heard or recognized. But if what you describe is the standard of judgment, how could a prisoner ever prove an Eighth Amendment violation?

CD: In practice, it is almost impossible to do so.

BLVR: That is disturbing. So… who ends up in solitary confinement?

CD: Anyone. Solitary confinement has been changed from an occasional tool of disciplinary convenience in our prisons—punishment for infractions—into a widespread form of preventive detention. Many prisoners have been sent to virtually total isolation and enforced idleness for no crime at all, not even for infractions of prison regulations. As I found out in my work in the Arizona supermaxes, contrary to the perception that these units house “the worst of the worst,” it is often the most vulnerable—especially the mentally ill—not the most violent, who end up in indefinite isolation. Placement there is haphazard and arbitrary. It also usually focuses on litigious inmates, political activists, those disliked by correctional officers, or alleged gang members, all called “security threat groups,” in a sinister foreshadowing of the ongoing war on “terrorism.”

BLVR: So if you are an inmate who knows enough about the law to help yourself or other inmates get fair treatment, or if you are a political activist among the prisoners, you just might end up in solitary confinement “for your own protection” or to make the job of wardens and officers easier. And once you’re there, there’s no telling when you’ll get out. And since this is an administrative decision rather than an intended evil perpetrated by an officer, it doesn’t count as punishment, can’t be cruel and unusual, and won’t be reviewed by any court! That is shocking.

CD: And the isolation can last for decades.

BLVR: Your book is pretty detailed about the conversations you had with wardens and corrections officers. How did you get access to the Arizona prisons? It’s not so easy to do.

CD: I know! Although Pelican Bay in California allowed 60 Minutes inside their walls—a revelatory visit that resulted in the famous case Madrid v. Gomez in 1995—the wardens of the Arizona units were proud of their policy: no journalists ever allowed inside. But I was just “the professor,” and I think there was something about my Southern accent—which comes out pretty strongly when I’m nervous (or drunk)—my interest in the history of Arizona incarceration, and my being a woman, that made me seem a perfect sounding board. Allowed unexpected access, I was granted interviews with wardens and correctional and classification officers. Although they did not allow me to talk with prisoners, I soon began getting letters from inmates who had heard about my work from their lawyers and family members.

BLVR: Let’s get to the uncomfortable question lurking in the background. Attitudes about prisoners in the U.S. are pretty retributivist. Lots of people tend to think that if you’re in prison, you did something wrong, deserve to be punished, and punishment needs to be more than a loss of liberty. It has to be unpleasant. So why should a law-abiding person who may never end up in a court of law or a jail care about what happens to lawbreakers?

CD: The penal project in any society goes hand in hand with the categorization and exclusion of those judged unfit or expendable. And as increasing numbers of our citizens find themselves without jobs, homes, or money, we will see that there are more “receptacles” waiting for them.

At a time when our government is labeling certain persons as threats—alleged terrorists, enemy aliens, illegal immigrants, ordinary people who want to get on airplanes— we need to consider how ever-larger groups of persons can be seen as outside the pale of care or empathy. The right to exclude and detain without notice of charges or evidence of guilt has become commonplace. This country has long had a reverence for police power: images of blacks set upon by dogs prompted by police, or the new brand of militarized but casual forces of the state assaulting unarmed citizens or peaceful protesters with batons or pepper spray. The quality of life professed for some depends on the surveillance and exclusion of others.

BLVR: The process of categorization of persons as threats and nuisances that happens in prisons also happens to all of us. Ugh. I always try to end my interviews on an up-note. Is that even possible here?

CD: It’s hard. But here in Tennessee I had the opportunity to teach a seminar with prisoners who had read The Law Is a White Dog. That experience was one of the most amazing of my entire teaching career. Not only did they “get” the point of the book, but they affirmed what I have always believed: for those who are oppressed, the law is far from abstract. It is not incomprehensible. Their interpretations and questions and courage demonstrated to me how to give flesh and blood to law, to make it count for those most affected by it. It is no accident that in Lewis v. Casey (1996), the Supreme Court decided that prison law libraries were not necessary for constitutional access to the courts. It is also no accident that prisoners who litigate best and help their fellow inmates often end up in supermax confinement.

So what can be done on a local level matters most now. As I wrote in “Words Behind Bars,” the limit on reading is currently one of the most damaging things happening in prisons, stripping prisoners of the right to know, to learn, and to think. We must fight against what is nothing less than behavior modification—what Justice John Paul Stevens called “close to a state-sponsored effort at mind control.” We should remember now, in the harrowing twenty-first century, what Frederick Douglass wrote in his 1845 Narrative. Describing how his mistress/owner, Mrs. Sophia Auld, changed from angelic to demonic, he recalled:

“Nothing seemed to make her more angry than to see me with a newspaper. She seemed to think that here lay the danger.” As educators, we can make a difference. I believe that prison practices are not accidental but rather a concerted attempt by many officials to transform large segments of the population so that they can never again return to meaningful contact with the outside world—even when out of prison. We can all stand up for the humanity of prisoners. And we can try to offer opportunities— for thought, for writing, and for reading—to those categorized as the worst of the worst.