At a key moment in Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982), the title character (played by Klaus Kinski) pacifies a murderous tribe of South American Indians by playing Enrico Caruso records on a portable phonograph mounted on his riverboat. Set in the early twentieth century, the story centers on Fitzcarraldo’s monomaniacal drive to build an opera house in the jungle and have Caruso sing there on opening night. Over the course of the film, both the phonograph and the tenor’s voice act as awesome, transcultural forces, capable of enchanting hostile natives and “civilized” Europeans alike. More than any other vocalist of his era, Caruso enjoyed a reputation for commanding a voice that approached mythical levels of greatness.

In the first quarter of the twentieth century, Enrico Caruso (1873–1921) was the best-known singer in the world—both an internationally renowned performer and the standard-bearer of the young international phonograph industry. He embodied, in fact, a new kind of public figure, one whose celebrity grew out of the emerging culture industries and circulated through the modern mass media. But Caruso’s stature as a celebrity depended on his charisma as much as his voice. After working with him, Edward Bernays, the pioneering public relations consultant, described Caruso’s star power in his 1965 autobiography. Caruso, he recalled, was like “a sun god” whose “light obliterated his surroundings,” and for those who came in contact with him, Bernays quipped, the experience was “gilt by association.” The pun was ironic: in addition to his groundbreaking fame, Caruso was the subject of the first celebrity trial of the twentieth century.

On Friday, November 16, 1906, Enrico Caruso was arrested for “annoying” a woman in the Monkey House in the Central Park Zoo. According to the next day’s newspapers, Caruso insisted on his total innocence and pleaded that the police must be making a mistake. According to some accounts, he also wept loudly in his jail cell until his friend and employer Heinrich Conreid, the director of the New York Metropolitan Opera, bailed him out. The woman whom Caruso allegedly molested identified herself as “Mrs. Hannah Graham of 1756 Bathgate Avenue, the Bronx,” but reports noted that she had been reluctant to become involved in a police matter for fear of jeopardizing her reputation as a “respectable” woman, and that she submitted her name and address only under pressure by the arresting officer, James J. Cain. The following day, it became evident that no one named Hannah Graham lived at the address the woman gave, and questions of her identity—indeed, her very existence—became a central issue in the tortuous affair that then began to unfold.1

The combination of Caruso’s fame with the salacious but pedestrian nature of the incident attracted widespread attention. Newspapers probed and exploited every conceivable facet of the incident, and as they did, the issues at stake expanded considerably. By the time the case went to court a week later, law and entertainment were mixing in new ways, with news coverage ranging from analysis of the slit pockets of Caruso’s overcoat to detailed descriptions of a monkey named Knocko, before whose cage the alleged incident took place. To contemporaries the affair was both a puzzle and a performance, and they welcomed such plot twists as “Hannah Graham”’s disappearance and witnesses who contradicted arguments they were supposed to corroborate.

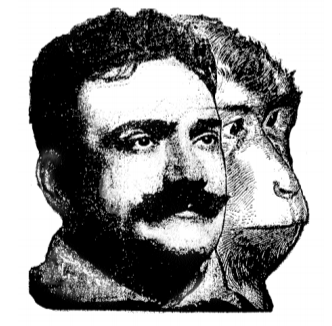

Then as now, the juxtaposition of the opera singer and the monkey lent an air of comic absurdity to the whole event. But for all its patent theatricality, the Monkey House Incident (as the episode became known) articulated serious social issues. Institutionalized police corruption and women’s daily battle against sexual harassment were no laughing matters. As the affair evolved, however, the known facts of the case doubled back on themselves and collapsed in a cloud of uncertainty. The prosecution and the defense gave wildly divergent accounts of what had transpired, and even when a legal decision was rendered, it left unanswered many questions raised in the courtroom and in the press. Ironically, the more uncertain the facts of the case were, the more real the issues it raised.

From the start, the shrewd Heinrich Conreid worked intensely to clear the name of the thirty-three-year-old Caruso, the Metropolitan Opera’s most valuable asset. Conreid knew, for example, that attendance at the Met was consistently higher on nights that Caruso sang. He began by issuing an indignant declaration to the press of Caruso’s absolute innocence, and he enlisted a prominent and well-connected former judge, A. J. Dittenhoefer, to lead Caruso’s defense. He also arranged for a sitting justice of the New York Supreme Court to speak on Caruso’s behalf with the magistrate who was to hear the case. Then, on the Monday following the arrest, he invited reporters to the opera house to what we would now call a press conference. There, Conreid did almost all of the talking. Most notably, this included the counteraccusation that the arrest was really part of a petty blackmail scheme to extort money from a random well-dressed gentleman, who happened to be Enrico Caruso. At the conference and in court, Caruso’s defenders stressed his limited command of English and noted that he might not have understood if a policeman had tried to extort money from him.

When the trial began, on November 22, the prosecution unleashed broader charges against Caruso, accusing him of harassing not one woman but several. As if to compensate for the courtroom absence of “Mrs. Hannah Graham,” whom the police still could not produce, patrolman Cain took the stand and testified that Caruso molested not only her, but also five other women in four separate incidents in the Monkey House, before he approached “Hannah Graham.”2

Cain described a sexual free-for-all, claiming he first observed Caruso approach two “respectable” women, who were accompanied by a male friend, and then stand so close behind each of the women that he pressed his knees into the backs of their legs. When this forced the women and their companion to leave the Monkey House, Caruso got close to two young girls, approximately twelve and fifteen years old, and rubbed his hand on the buttocks of the older girl. The next incident, Cain said, came when Caruso rubbed the front of his body against the hips of “a colored lady” whom he cornered, followed by the penultimate incident—another pass at the two young girls, who had left the Monkey House and then returned. Finally, Cain said, Caruso approached the woman known as Hannah Graham, pressed his legs and body against her, and touched her with his hands through slits in his pockets. “Mrs. Graham,” Cain recounted, then struck out against Caruso, pushing him backward, at which point Cain stepped forward and placed him under arrest.

This remarkable account strained under cross-examination. First, as Caruso’s counsel, A. J. Dittenhoefer, asked, “You allowed him to go from one [woman] to another without arresting him?” It seems extraordinary that Cain watched Caruso go from victim to victim without once interfering with him or even speaking to him, although he testified to having watched Caruso for three quarters of an hour. In response, Cain claimed he was waiting for the right moment to catch Caruso in flagrante delicto, but it seems Caruso’s repeated assaults on at least five different women would have been incriminating enough. Moreover, it appears unconscionable that Cain made no attempt to protect or even to warn the women and girls after he understood Caruso’s intentions and method. Another problem with Cain’s testimony stemmed from his assertion that Mrs. Graham had had a small child, between four and six years old, with her in the Monkey House. He claimed the child did not accompany them to the police station, and wasn’t under the care of anyone else present, but it is hard to believe that this “respectable” woman would have left a young child alone, especially in an environment as evidently hostile as the Monkey House.

The significance of Cain’s testimony was amplified by the fact that he was the principal witness in the case. Much to the defense’s surprise, when the trial began Cain, not Graham, was listed as the official complainant, and despite several claims by the police that they had found “Mrs. Graham” and were about to produce her in court, “Mrs. Graham” never appeared. Instead, the only significant witness called by the prosecution to corroborate Cain’s testimony was a consumptive loafer named Jeremiah McCarthy. His recollections on the stand initially seemed to support Cain’s, but later in the trial his credibility came into doubt when Dittenhoefer showed that McCarthy had been fired from his most recent job for dishonesty and possibly stealing.3 Beyond him, the prosecution offered little else. Newspaper appeals notwithstanding, none of Caruso’s six alleged victims stepped forward to support the accusations, nor did any other bystander who was in the Monkey House that day.

For the defense, Caruso took the stand and, through an interpreter, denied everything. He acknowledged seeing “Hannah Graham” but claimed she eyed him flirtatiously and that he did nothing to initiate any kind of contact. He testified as well that he had spent only a few minutes in the Monkey House, not forty-five minutes, and that Cain had arrested him outside as he was leaving, not in front of the monkey cage. The defense then called three witnesses. One was Richard Barthélmy, Caruso’s French voice coach, who confirmed the time that Caruso left the Hotel Savoy, where he lived. Another was Heinrich Conreid, who testified about Caruso’s limited English. The third was a German-born attorney and former U.S. diplomat, Adolph Danziger, who testified he saw Caruso in the zoo but witnessed no untoward behavior. However, under cross-examination Danziger also conceded that Caruso was a personal friend of his and, more significantly, that he had not spoken with Caruso when he saw him in the zoo because the singer was standing so close to some other people that he believed Caruso to be part of their party and did not want to intrude.

After three days of testimony, defense and prosecution rested and the magistrate delivered a judgment: he found Caruso guilty and fined him $10, the maximum amount allowed by law. Immediately, the defense began an appeal on legal and procedural grounds, but by this time tangential social issues raised by the incident had taken center stage. By coincidence, zoos had recently been in the news in New York, when, two months earlier, the Bronx Zoo had “exhibited” a twenty-five-year-old pygmy man from the Congo named Ota Benga. Controversy erupted; crowds rushed to see him. Some historians have interpreted the incident as an expression of American ideas about race and empire at the turn of the century. In light of this episode, the Monkey House Incident might be seen as an expression of a concurrent conflict over immigration and American national identity. Each day of the trial, throngs of Italian and Italian-American opera fans had flocked to the courthouse, filling the halls with “Bravo!” and “Viva Caruso!” whenever the tenor entered or exited. Although a great class divide separated Caruso from his devoted Italian supporters, he was born of humble origins, exuded a folksy charm (though perhaps less so in court), and remained forever adored in poor and working-class immigrant neighborhoods. With the presence and the cheers of Caruso’s Italian supporters, the whole incident embodied the contemporary clash between native-born Americans and immigrants.

Caruso’s arrest occurred only weeks after William Randolph Hearst narrowly lost his bid for the governorship of New York, a campaign based heavily on support from immigrants, and it came only two years before the New York debut of The Melting Pot, Israel Zangwill’s landmark play about the integration of immigrants into American culture. Throughout the era, there was intense debate over the impact of immigrants in the United States, and vitriolic attacks on immigrants’ moral character were not uncommon. The Monkey House Incident pitted the native, largely Irish police force against the Italian Caruso and the foreigners he called to his defense—Danziger, Bartélmy, and Conreid. The prosecutor, Deputy Police Commissioner James Mathot, laid bare this climate of nativist hostility in his closing argument, fulminating against both Caruso and his rambunctious paisani in the courtroom. “They ask us why Hannah Graham has not appeared,” Mathot said in his summation.

It is because of the crowd of moral perverts and dogs and curs out there in the courtroom who come here to listen… Our mothers and our sisters are not safe in the streets; they cannot go about without being subjected to insult by this scum from the lazaretto of Naples.

Meanwhile, foreign reaction to the incident highlighted how curiously American the incident was. In London, people believed the American police were corrupt and therefore that Caruso was innocent. In France, newspapers found the affair insignificant and typical of Americans’ puritanical sexuality. In Germany, the Berlin Post lauded the Americans for trying to make public places safer for women. And back in the United States, a letter-writer to the New York Times argued that the case could teach the French and Italians something of the importance of women’s rights.

These latter arguments raise an important question: to what extent was the affair really about the security and dignity of women? On the one hand, the incident triggered a public discussion about the daily harassment of women in New York. When a man wrote in to the New York Times to say he had never seen any improper treatment of women in public places in New York, numerous women quickly responded with assertions to the contrary. Typical were letters claiming that inappropriate behavior by well-dressed men was far from unusual and praising the police prosecution of the case. According to one letter about harassment on elevated trains, “these detestable practices do not seem to be confined to any particular line of cars nor any one class of men.”

On the other hand, few who were concerned about women’s virtue and security were likely to be comforted by the legal proceedings. For one thing, the charge against Caruso was not personal assault but rather disorderly conduct, which was only a defense of women in an indirect way. For another, part of Caruso’s defense strategy was to impugn Hannah Graham’s character as a virtuous, “respectable” woman, asserting that, whoever the woman was, she had initiated contact with Caruso with a flirtatious glance. Such a strategy only confirmed women’s fears about the hazards of taking legal action against a harasser. Finally and most importantly, Cain’s testimony that he watched Caruso commit four incidents of harassment before he could intervene would have reassured no one. If his was a battle for the protection of women, the results suggest a Pyrrhic victory.

Even the argument that the arrest was an attempt to restore law and order must contend with the strong suggestion of police misconduct. Conreid, Dittenhoefer, and the New York Herald, for example, all reported unsolicited letters about other men arrested for molesting women in Central Park who avoided notoriety by paying off the policeman and “victim.” One such alleged incident even took place in the Monkey House. Indeed, even the former New York City police chief, William Devery, joined the doubters’ chorus. “The arrest of Caruso… was an outrage,” he told the New York World. “His conviction was had on no evidence at all… The whole thing looks to me like a shake-down. Certainly the arrest was phony.”

By way of a defense, Deputy Police Commissioner Mathot responded to these accusations by asserting that Caruso was not the first prominent man to be arrested for this type of indecent behavior. Other distinguished persons, he claimed, including a bishop and various highly placed businessmen, had similarly been arrested, but these cases had been kept out of the press to avoid unnecessary embarrassment to the “mothers and sisters and daughters and wives whose social position would be ruined by such an exposure.” Intended to quell rumors, this disclosure had the opposite effect, unleashing a firestorm of condemnation and speculation, and calls for a full investigation. For several days newspapers demanded to know if there was any truth to Mathot’s statement, and only after repeated denials by police chief Theodore Bingham and his dismissal of Mathot did the flap begin to subside.

So did Caruso do it? Did he molest the woman who called herself Hannah Graham—or anyone else in the Monkey House that day? As problematic as the case against him was, and as suggestive as the claims of police blackmail, circumstantial evidence suggests that this kind of behavior toward women might not have been out of character for Caruso. A 1903 newspaper profile remarked that Caruso’s first love was garlic, and his second was young American women. A 1905 article noted, “Right here it might be apropos to chronicle that Signor Caruso likes our American oysters.… And the American women!… Same as the oysters. Loves ’em.” Then, a 1906 profile focused on Caruso’s playful penchant for chasing women, which included running around backstage at the Metropolitan Opera. “It is said that you kiss all the beautiful girls that let you!” the reporter said to Caruso. “‘I kiss the homely ones, too,’ he replied, ‘to do penance.’” The lighthearted report concluded, “He runs after Nordica, Fremstad, Marion Weed, at rehearsals, and behind the scenes at plays. He tries to kiss them, but they do not let him.” These accounts probably have as much to do with the emerging emphasis on male opera stars as with Caruso’s behavior, but they do cast the entire incident in a slightly different light.

Caruso’s celebrity was at the core of the Monkey House Incident, and that the affair did no lasting damage to his career was one of its most significant outcomes. Credit for this goes in part to Heinrich Conreid, one of the world’s leading impresarios. Conreid knew the importance of good press and courted media coverage accordingly. From this point of view, the publicity value for Caruso could hardly be overestimated; the Pittsburgh Gazette quipped, “To think that Caruso’s not paying one cent for all this advertising.” In the end, the real verdict came in the opera house, not the courthouse. With much anticipation, Caruso made his season debut at the Met in La Bohème on November 28, 1906, and when he took the stage, he was greeted primarily with rousing, indulgent applause. Under headlines such as “Caruso Triumphs Before Opera Jury,” newspapers reported a widespread consensus on Caruso’s popular vindication. And it probably did not hurt that Conreid had circulated among the press a letter of support for Caruso from fellow Metropolitan Opera members.

Five months after his conviction, Caruso and his attorneys dropped his appeal; pursuing it, he said in a statement, would “only result in stirring up a matter that is now forgotten.” This was wishful thinking. Edward Bernays noted that memories of the incident still vexed Caruso in the late 1910s. Whether the tenor was troubled or not, as the incident faded from the newspapers it passed into lore. Forty years later, the writer A. J. Liebling recalled (in Between Meals) that he first encountered the Monkey House Incident as a well-worn myth, which he “accepted as fully as the story of George Washington and the cherry tree.” Curiously, he also noted that he had since “learned” that the whole affair had been “a press agent’s trick, put up to attract attention to the tenor’s appearance in a new role.”4

Seen nearly a century later, the Monkey House Incident marked a new emerging relationship between law, entertainment, and entrenched social problems, in which real and fiercely contested issues were illuminated by the spectacle of celebrity. At the same time, the incident seems to mock New York’s other great scandal of 1906–1907: the murder of architect Stanford White by Harry Thaw over White’s affair with Thaw’s wife, and the sensational trial that followed. With Caruso, the incident in question did not concern murder or even adultery, but the alleged molestation of a woman whom many believed did not exist, in front of a monkey named Knocko. Thaw was later found not guilty by reason of insanity; Caruso was convicted and fined $10.

In the final reckoning, Knocko might well be seen as the one certain victim in the Monkey House Incident. The affair sparked a surge of interest in the Monkey House, which stimulated Knocko to perform more and more for the crowds gathered before his cage. Within a short time, Knocko fell ill and was removed to the Central Park animal hospital. According to the New York Times, zookeepers attributed his illness directly to overexcitement. A day later, Knocko died. The last trace of Knocko is an article reporting that his body was to be sent to a taxidermist and then put on display at the American Museum of Natural History.