- LAUREATE: François Mauriac (1952, France)

- BOOK READ: Vipers’ Tangle, trans. Warre B. Wells

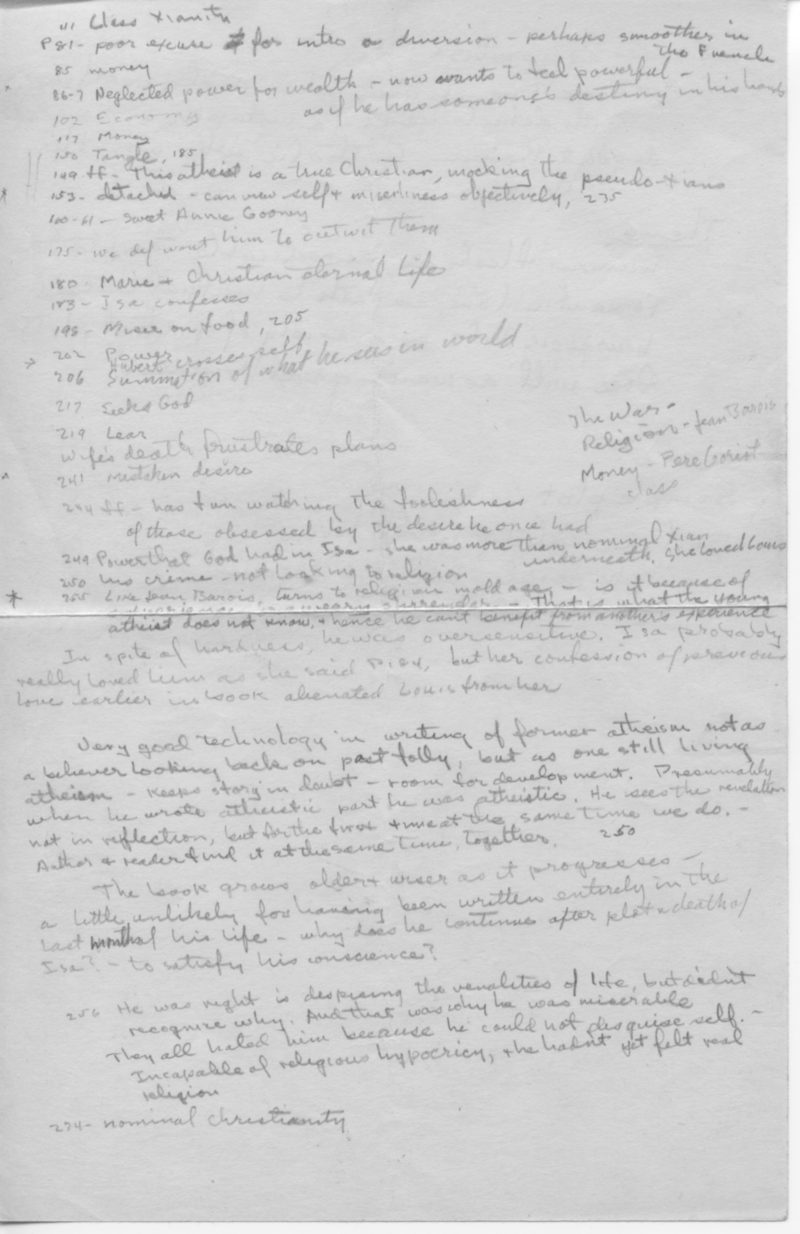

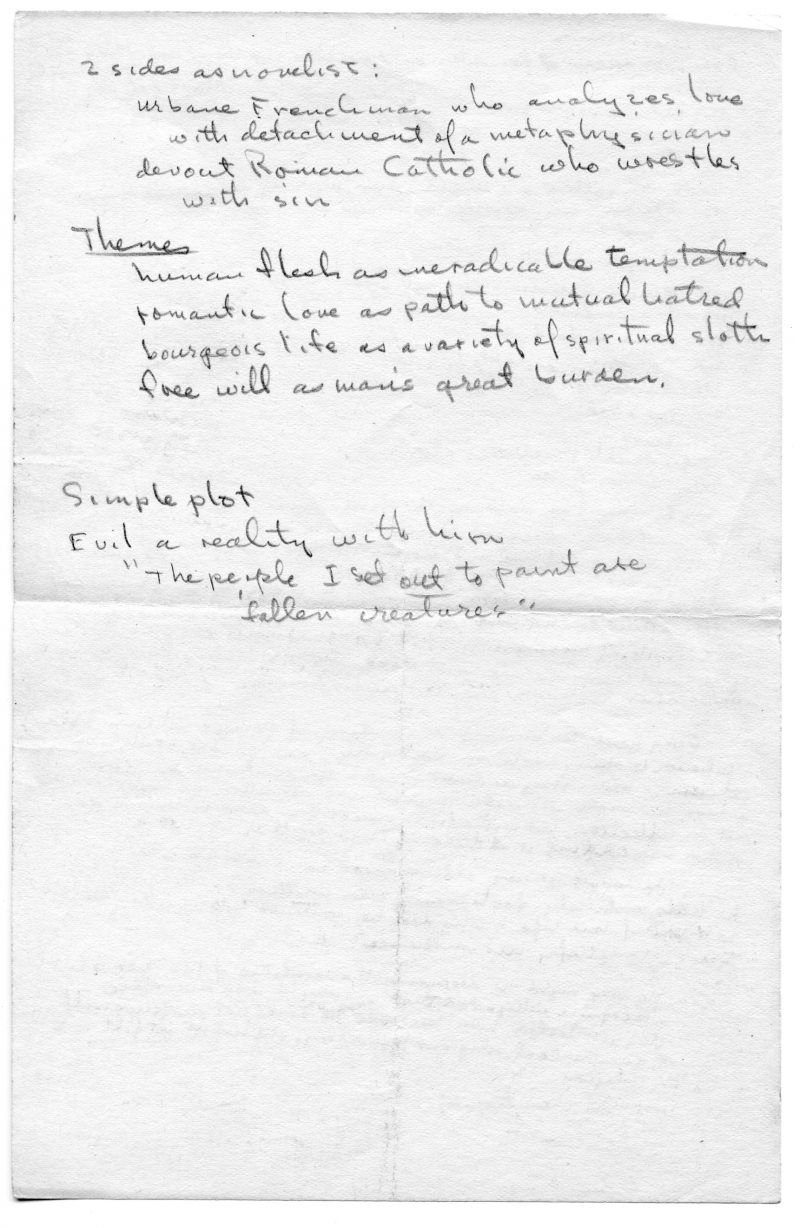

Above and below: Pages of notes found in

Daniel Handler’s copy of Vipers’ Tangle.

Some years ago I boarded an airplane and was greeted by the gentleman sitting next to me. It was the dawn of the iPod, and the fact that we were both listening to this new device was apparently reason enough to chat. He asked me if I agreed it was a terrific little machine and I said I did. He asked me if the shuffle function wasn’t really cool and I said it certainly was. Then his eyes lit up and he said, “Wouldn’t it be amazing if we both happened to be listening to the same thing right now?” and we both looked down at my little screen to see what was playing.

It was The Spellbinding Piano of Burma.

Part of my life will always be lonely. I have terrific family and friends and a professional life about which there can be no complaint, but much of my time is spent traipsing around literature in one way or another, and my traipses tend to be generally unaccompanied. I’m usually not reading what other people are reading. I get accused of playing cooler-than-thou—Me? Oh, I’m reading that Henry Parland book Eliot Weinberger likes—but the truth of the matter is that I just like this stuff. I like the Scandinavian modernism. I like the self-published queer rants. I like the secondary gothic novelists and the autobiographical verse novels of decades gone by. I like the forgotten essayist the NYRB has put back into print, and the uncool novelist New Directions keeps in print, and the wild experiments Ugly Duckling Presse prints itself. The only thing I don’t like about it is that nobody else is reading it. I don’t like that nobody else is reading it, because it seems bad for the world, which would be much improved if everyone knew who Barbara Comyns is. I don’t like that nobody else is reading it, because then it’s hard to find. And I don’t like that nobody else is reading it, because I don’t have anyone to talk to when I’ve read it myself. It’s tough, at a party, to say, “I just finished this novel, Four Frightened People” with the utter certainty that the other person will just say, after a lengthy sip, “Huh.”

It’s a little sad that the Nobel Prize in Literature is full of books that fall into the nobody-reads-it category. When I decided on this somewhat-harebrained scheme of reading one book by each winner, I decided I’d try to buy as many of the books as possible in the bookstores in my hometown of San Francisco. Armed with my long list, I started with the stores that sell new books and I found maybe one-tenth. I moved on to my favorites, the used-book stores, full of dusty obscurities and startling treats, and raised the fraction to about half. The other fifty or so books—books by authors awarded the highest literary prize in the world—were too obscure even for stores selling books nobody reads. Most of this missing half were from the earlier winners—the prize was first awarded in 1901—but even some of the more recent Nobels are on nobody’s bookshelves. (Read any Dario Fo lately?) This is sad because of the usual things that we book-types like to be sad about, but it’s also sad for me, personally, right now, because it’s lonely to read these books and feel that, like The Spellbinding Piano of Burma, they’re echoing in my head and my head alone.

(And I’ll pause here and say to the scattered souls who are furiously replying, “But I read Dario Fo all the time!”—don’t you feel, you know, lonely?)

I know I could try to cure my own loneliness the usual way—by forcing my own peculiarities on others standing nearby. And indeed I often suggest, to personal friends and general readers, that they join me in my traipse through the Nobel prizewinners. My journey so far has turned up many a book that I’ve enjoyed thoroughly, books that have challenged my every assumption about what literature is and does and tastes like, and books that have suggested new ways of literature I’d never have dreamed up with my nose in a best seller. But they’re not books I’d really recommend the way you just recommend a book to somebody. It’s like saying The Spellbinding Piano of Burma is a great album. It is. But if somebody says, “I need something new to listen to,” I’m going to say something more like The Five Ghosts, which is an album you can just throw on and love. The writings of Wole Soyinka, not so much.

And so here we are at Vipers’ Tangle, by François Mauriac, about midway on the Nobel obscurity spectrum, roughly equidistant from Toni Morrison and, oh, let’s say Grazia Deledda. Mauriac was a high-profile intellectual in France, particularly after the Second World War, when he would tussle in the pages of various newspapers with Albert Camus, and this novel reads like a novel by a public intellectual, in that it’s an unbridled, uninterrupted monologue in the service of an idea.

The novel consists largely of a series of letters from Monsieur Louis, an aging lawyer, to his wife. He’s not pleased with her:

If I have not given you anything on your birthday for years, it is not because I have forgotten; it is by way of revenge. It suffices…The last bunch of flowers I received on my birthday, my poor mother plucked it with her deformed hands. She had dragged herself for the last time, despite her weak heart, as far as the rose-walk.

The voice is like this for the duration—cold and woolgathery, with the sort of psychological signposts that probably seemed more subtle at the time. Louis’s wife has failed to live up to the standards displayed by Louis’s mother, for a variety of reasons, ranging from an unpleasant family—“that obese grandmother of yours, who hid her bald skull under black lace”—to continuing thoughts, at least as far as Louis can see, of an old flame. A loving household slowly constricts into silence and tension, chronicled and justified by Louis, who in relating his detached and loveless life gradually finds reason to believe that joy is possible. The epigraph from Saint Teresa of Avila gives us a hint, in case you weren’t aware of Mauriac’s Catholicism; at the close of the novel Louis is stumbling his way toward grace.

It’s a tough gambit, the hero finding redemption through his own inner machinations rather than any contrivance of plot, and the transformation does feel a bit convenient, not to mention something of a letdown, as Louis’s icy seethings melt into something a little more watery and a little less fun. The novel made me think of Death on the Installment Plan, an uninterrupted French rant that never softens—an even-less-pleasant narrator, but a more exciting read. The delights of Vipers’ Tangle are in the language of anger—“Your hand groped for my face in the darkness… but perhaps that hand of yours did not recognize the familiar features in that set face, with its clenched teeth”—and occasional loopy asides like “It was so hot that we could not keep the shutters closed, despite your horror of bats.” The novel is less compelling as it moves toward the light, like any story where the villain turns out to be not so bad after all. You’re happy to hear it, up to a point, but a little disappointed that the villain didn’t end up tossed to a pack of ravenous wolves rather than welcomed into church.

Or maybe that’s just me. It certainly felt like just me reading it. I closed the book wondering what I might say about Vipers’ Tangle, but I also wondered who I might say it to. Then I found the answer, in the back of the book. My copy of Vipers’ Tangle was one I already owned, sitting unread on my shelves after I bought it who-knows-when. It’s an old hardcover, with that used-book smell and a few sticky pages at the back. I unstuck them, and a piece of paper—I swear this is true—fell into my hands. I unfolded it, and in tiny, bygone handwriting covering both sides of the yellowing sheets, I read notes from another reader.

Most of the notes are direct comments on the text, with page notations—the exact kind of notes I take for a piece like this one. He—and I’m pretty sure the writer is male, as we’ll see—finds a flourish on page 81 a “poor excuse for intro or diversion—perhaps smoother in the French” and finds a description on page 206 a “summation of what he sees in the world.” But on the other side of the sheet, the note-taker lists some broader ideas, with the quaint tone of an old-fashioned English teacher:

2 sides as novelist:

Urbane Frenchman who analyzes love with detachment of a metaphysician

devout Roman Catholic who wrestles with sinThemes

human flesh as uneradicable temptation

romantic love as path to mutual hatred

bourgeois life as a variety of spiritual sloth

free will as man’s great burdenSimple plot

Evil a reality with him

“The people I set out to paint are fallen creatures.”

I liked considering Vipers’ Tangle in a context in which “free will as man’s great burden” was something you could say without flinching, but I was most intrigued by that “fallen creatures” quote. I didn’t remember it from the novel, so I thought it might be something Mauriac had said. I laid this old, lost sheet of paper next to my laptop and typed the quote into Google.

I got just two hits—which looks strange in this time when there’s chatter about everything—and the top one was from the archives of Time magazine, a review of Mauriac’s novel The Loved and the Unloved, from the October 6, 1952, issue. The “fallen creatures” quote is indeed credited to Mauriac, from an essay appended to the novel. But what struck me was how the review began:

As a novelist, François Mauriac has two sides: 1) the urbane Frenchman who analysizes love with the detachment of a metaphysician, and 2) the devout Roman Catholic who wrestles with sin.

Mauriac’s latest novel, The Loved and the Unloved, rehearses his usual themes: human flesh as uneradicable temptation, romantic love as path to mutual hatred, bourgeois life as a variety of spiritual sloth, and free will as man’s great burden.

I looked from the screen to the piece of paper and back again, the identical and unlikely wording a bridge, some fifty years apart between two readers—let’s face it, the only two—of my copy of Vipers’ Tangle.

It’s too bad the review is uncredited, as it’d be fun to shout out my companion, my fellow traipser into François Mauriac, by name. (Megan Roberts, intern extraordinaire at the Believer, traced the review to one of three men—Max Gissen, Theodore E. Kalem, or Henry Bradford Darrach Jr., all deceased—before the trail went cold.) And of course it’s possible that I read those notes the wrong way round, and that some other lonely reader of Vipers’ Tangle sought out, before the days of web archives, someone else who was thinking about Mauriac, and jotted down Time magazine’s phrases for their own literary traipse. But in that moment the whole enterprise of reading books shone clear. A neglected but highly prized writer, a reader’s intimate glimpse at a critic he’ll never meet, an old, used edition given new meaning thanks to the web—everything came together. With one hand on an old sheet of penciled notes, the other clicking links, I felt that sharp, startling spark when you meet someone you like—the exact opposite of loneliness. It’s not dissimilar to the feeling of coming across a perfect phrase, some prescient idea or image, in a book; it’s a different kind of read, but it’s a read nonetheless. It has a music of sorts, foreign but soothing, strange and familiar at the same time, that amazes and transfixes me—as a reader, as a writer, as a person. Against all odds, in the dust and blur of the world, the obscurity and discovery of literature is spellbinding.