“’Tis but thy name that is my enemy.”

—William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

I.

I am named after the daughter my father lost.

I remember the day I first learned about her. I was eight. My father was in his chair, holding a small white box. As my mother explained that he had a dead daughter named Jeanne, pronounced the same as my name, “without an i,” he opened the box and looked away. Inside was a medal Jeanne had received from a church “for being a good person,” my mother said. My father said nothing. I said nothing. I stared at the medal.

Later that day, in the basement, my mother told me Jeanne died in a car accident in New York when she was sixteen, many years before I was born. Two other girls were in the car. Jeanne sat between the driver and the other passenger in the front seat. The driver tried to pass a car, hesitated, then tried to pull back into her lane. She lost control and Jeanne was thrown from the car and killed instantly.

“Your father blames himself,” my mother said. “He can’t talk about it.”

“Why?” I asked.

“He gave her permission to go out that night.”

After Jeanne died, my father bought two burial plots next to one another, one for Jeanne and one for himself. When he and his first wife divorced, she stipulated that he forfeit his plot, and he agreed. Soon after the divorce, he went to court again, this time for beating up a bum on the street. “Why should you be alive?” my father had asked him. “You’re not working and my daughter’s dead.” The judge remembered my father and let him go.

“Did you know his first wife?” I asked my mother.

“No, he was divorced long before I met him. All this happened in New York.”

I lived in Ohio, where my father and mother met. In my mind, New York was made of skyscrapers, taxicabs, and car accidents.

“What did Jeanne look like?”

My mother said she had never seen a photo.

That spring I painted portraits of Jeanne in watercolor. I titled them Jeanne. My art teacher told me she was disappointed that such a good student could misspell her own name. From then on, I included an i.

II.

Federico García Lorca insisted that a heightened awareness of death is a requirement for the artist. In his 1933 lecture “Theory and Play of the Duende,” Lorca attempted to define artistic inspiration, and argued that an artist must acknowledge mortality in order to produce art with duende, or intense feeling. “The duende,” he wrote, “won’t appear if he can’t see the possibility of death, if he doesn’t know he can haunt death’s house, if he’s not certain to shake those branches we all carry, that do not bring, can never bring, consolation.”

The medal, her age, and the car accident were all I knew of Jeanne, but those details were enough to supply my imagination. At a state writing competition in junior high, I wrote a story about three girls standing in line for a movie that they have no intention of seeing. They want to be seen. They choose to stand next to a movie poster that shows a car crashed into a tree. Two of them chew gum and talk about boys. The other girl is thinking about her sister who died in a car accident. “Anne wants to lose herself in a movie” is the only sentence I remember. Her sister’s name was Annie. I titled the story “i.” I received first place.

I told myself Jeanne won.

III.

Parsed from the Greek, necronym literally translates as “death name.” It usually means a name shared with a dead sibling. Until the late nineteenth century, necronyms were not uncommon among Americans and Europeans. If a child died in infancy, his or her name was often given to the next child, a natural consequence of high birth rates and high infant mortality rates.

Ludwig van Beethoven, for example, had a brother named Ludwig Maria who was born in April 1769 and lived for only six days. The composer was baptized on December 17 of the following year and was likely born the day prior, given church customs in the Catholic Rhine country where he lived (no official record of his birth date exists). Marketed as a musical prodigy, Beethoven often felt it necessary to prove his age. In an 1809 letter to his friend Wegeler, he asked for his baptismal certificate: “…take note of the fact that I had a brother born before me, who was also called Ludwig, but with the additional name of ‘Maria,’ and who died. In order to determine my true age, you should, therefore, first find this Ludwig. For I know that other people, by giving out that I am older than I really am, have been responsible for this error—Unfortunately I lived for a while without knowing how old I was.”

“When your dad was a boy,” my mother told me, “and this was long ago—you have to remember he lived through the Great Depression—it wasn’t unheard of to name a child after a dead relative, especially a dead child.”

In their 1989 Dictionary of Superstitions, folklorists Iona Opie and Moira Tatum offer one reason for the necronym’s decline: many parents feared it was a murderous curse.

Another possible curse: the name haunts the child for life.

IV.

Every Sunday as he entered the church where his father, Theodorus, preached, Vincent van Gogh passed a gravestone marked VINCENT VAN GOGH.

The artist’s brother Vincent was born, and died, March 30, 1852. The artist was born March 30, 1853. I remember being sixteen years old in the Toledo Museum of Art, staring at his painting Houses at Auvers, when I heard a museum guide say this. Whether the knowledge affected van Gogh—that he shared both his name and birthday with a dead sibling—remains unknown, the guide said.

“Does anyone have any questions?” he asked.

My mind filled with loud, hurried thoughts and just as suddenly emptied, like a flock of birds scattering from a field.

I was sixteen, the age Jeanne would always be.

“No questions?” he said, and the tour followed him into another gallery. I stayed behind with Houses at Auvers.

In the center of the canvas stands a white house with a blue-tiled roof. A long stone wall climbs the canvas from left to right in loose brushstrokes. I remember the gray-blue sky looked numb to me. I reminded myself that I was looking at the representation of a white house. I could not open its door and step inside. But when I reminded myself that van Gogh was named after a dead sibling, Houses at Auvers appeared almost three-dimensional.

Thinking of Jeanne, I left the painting and carefully drove home.

V.

My father was eighty and dying in what used to be the living room. His bed was underneath my painting of a tree, a bad imitation of van Gogh—a high-school assignment that my parents had insisted on framing.

I was eighteen and quietly reading beside his bed. I was supposed to write a paper about Hamlet for my Shakespeare seminar at college.

“He was a man, take him for all in all,” Hamlet says of his dead father. “I shall not look upon his like again.”

I would write about grief and the question of madness.

I knew that my father “had really lost it” after Jeanne died, and I already felt myself “really losing it,” too. At night I tied nooses, scratched the soles of my feet. I heard voices that told me I needed to die. I told no one, because it all seemed rational: my father was dying and so of course pieces of my mind would die, too. He and I were extremely close. Shortly after I was born, he retired from his painting job at the hospital where he and my mother met. As a child I told him, “I’m going to be a painter like you.”

“I was just a maintenance painter,” he explained. “But you can be a great painter.”

When I was a small girl, he and I played a game called “Art Museum.” I painted dozens of pictures (nothing spectacular: tall, rectangular houses with triangle roofs, trees, our dogs and birds and ducks) that I then displayed throughout the house. He would walk from room to room, contemplate my paintings, and always say, “I want them all.”

As I sat there at his deathbed, annoyed by its irony (what was a deathbed doing in a living room?), my father opened his eyes and gasped at some vision hovering above his bed. I stood before the vision, trying to block whatever it was that was frightening him, but he looked through me as if I didn’t exist.

“Dad?” I said. “Do you see me?”

I called for a hospice nurse. She and my mother appeared in the doorway.

“He saw something,” I told them.

The nurse said that sometimes happens.

“They see the dead,” she explained. “Someone from their past comes to them.”

Jeanne.

VI.

I recently combed through van Gogh’s letters and was surprised to find that he mentions his dead brother in a condolence note to a former employer. In the letter, dated August 3, 1877, van Gogh tried to comfort Herman Tersteeg, whose three-month-old daughter had died: “My Father has also felt what you will have been feeling these past days. I recently stood early one morning in the cemetery at Zundert next to the little grave on which is written: ‘Suffer the little children to come unto Me, for of such is the kingdom of God.’ More than 25 years have passed since he buried his first little boy there, in those days he was moved by a book by Bungener, which I sent to you yesterday, thinking it would be a book after your own heart.”

The book he refers to is likely Laurence Louis Félix Bungener’s Keeping Vigil Over the Body of My Child: Three Days in the Life of a Father. There Bungener describes, in the form of a diary, how religion helped him through the death and burial of his daughter. First published in 1863, when van Gogh was ten, it is Bungener’s only book devoted to his daughter. For van Gogh to remember his father reading it, and then to mention his own recent visit to the child’s grave, at the age of twenty-four, shows his overwhelming sympathy for his parents’ grief. That he quoted the gravestone word for word, paired with his repeated use of little, I find heartbreaking. He ends the letter, “Do not think ill of me for writing to you as I have done, I felt the need to do it.” As far as I can tell, nowhere else in the recovered family correspondence is the dead child acknowledged.

An awareness of his father’s grief clearly persisted in van Gogh. With that in mind, I researched the dates of his self-portraits and found that the first surviving one was painted after his father’s death—as if only then could van Gogh become his own person. Van Gogh went on to paint more than thirty self-portraits, which reveal his changing technique and psychological decline. In September 1889, while hospitalized in Arles for what his doctors called “acute mania with generalized delirium,” he simultaneously painted two versions of himself. In one, he is thin and pale against a dark violet-blue background. In the other, he appears healthy against a light background. Of the portraits, van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: “People say—and I’m quite willing to believe it—that it’s difficult to know oneself—but it’s not easy to paint oneself either.” That same September, van Gogh painted himself one last time, and gave the work, Self-Portrait Without Beard, to his mother for her birthday.

Then came another Vincent van Gogh.

In January of 1890, Theo’s wife, Jo, gave birth to a boy whom Theo named Vincent. He chose van Gogh, the boy’s uncle, to be godfather. “I’m making the wish,” Theo wrote to his brother, “that he may be as determined and as courageous as you.” (A letter from Jo to her family, dated the previous June, reveals that the name had been chosen shortly after she became pregnant: “Theo would like ‘Vincent,’ but I don’t attach much importance to names.”)

In a long, congratulatory reply, van Gogh suggested they call the child Theo in memory of their father, Theodorus. “That would certainly give me so much pleasure,” van Gogh explained. He then wrote to his mother: “I’d much rather that he’d called his boy after Pa, whom I’ve thought about so often these days, than after me, but anyway, as it’s been done now I started right away to make a painting for him, to hang in their bedroom. Large branches of white almond blossom against a blue sky.”

Less than six months later, at thirty-seven, van Gogh died from a gunshot wound to the chest. According to Theo, who remained at his brother’s bedside until the end, the artist’s last words were“La tristesse durera toujours” (“The sadness will last forever”). Theo suffered from syphilis, and after his brother’s death his health declined rapidly. Six months later, Theo died. He is buried next to van Gogh in an Auvers cemetery.

When I think about Jeanne, I see Houses at Auvers, painted the last year of van Gogh’s life.

VII.

My father is buried underneath a tree that looks like the one I painted. When I was a child, his ex-wife offered him the plot next to Jeanne; he refused.

“I have a family here,” he had said.

The last time I visited his grave, I told the dirt that as much as I thought about Jeanne and how much I wanted to be like Jeanne, I spent more time not thinking about Jeanne.

In 1964, the psychologists Albert C. Cain and Barbara S. Cain coined the term replacement child to refer to a child conceived shortly after the parents have lost another child. Their article “On Replacing a Child” describes replacement children as suffering from neurosis or psychosis in psychiatric settings. Born into an atmosphere of grief, the new child is “virtually smothered by the image of the lost child,” the authors observe. “These children’s identity problems [were such that] they could barely breathe as individuals with their own characteristics and identity.” Fifteen years later, the clinicians Robert Krell and Leslie Rabkin identified three types of replacement children: bound, resurrected, and haunted. The parents of a “bound” child may be overprotective physically, but remain emotionally distant in preparation for another loss. A “resurrected” child is treated as a reincarnation of the dead sibling. A “haunted” child lives in a family overwhelmed by guilt, which imposes “a conspiracy of silence.” I am not a replacement child, according to the precise definition of the term. Nor did my father make me feel like one. He never mentioned my half sister. If anything, I was left half-haunted.

My senior year of college, when I was hospitalized for a “mixed episode” of mania and depression (racing thoughts, hallucinations, overdose), I told doctors that my father was dead. I told them that my father had lost a daughter named Jeanne.

“He added the letter i to my name,” I said.

I tried to explain that her death at sixteen almost destroyed him, and that his death was destroying me.

“This is grief,” I said.

The doctors said grief operates differently.

My father died and I was not in the room with him. Would Jeanne have stayed in the room? Was she the vision he saw?

VIII.

After I graduated from college, I moved to New York. I remember often thinking in those days: I live not far from where Jeanne died. But I didn’t know where she died, exactly.

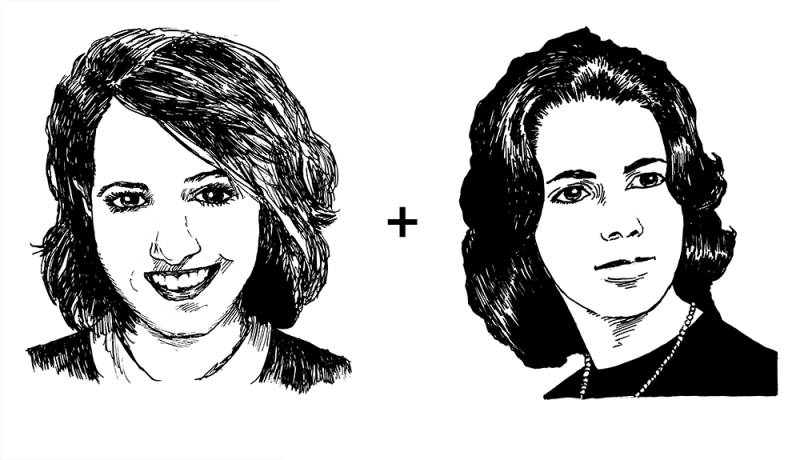

One Sunday afternoon, in the office of the literary magazine where I worked, I was editing an essay about the history of dissection. The essayist wrote that the English physician William Harvey dissected the bodies of his father and sister. At that moment I felt as if a gust of wind had opened a heavy door. I thought of my father and Jeanne. What did his body look like inside his coffin? What had Jeanne ever looked like? I went online and searched for “Jeanne Vanasco.” The page of results asked, “Did you mean Jeannie Vanasco?” I scrolled down to a link for her high-school memorial page and clicked. Someone had posted Jeanne’s photograph. For the first time, I could see her face. I tried to enlarge it, but she only became more difficult to see: dark, wavy hair cut above her shoulders, head turned slightly to the left, a pearl necklace. I stared at the photograph as if looking at her for long enough might allow me to enter the mind and body of the girl whose death almost destroyed my father. A week later I was hospitalized again, for a “mixed dysphoric state.” Was it possible that I was grieving Jeanne? But how do you grieve someone you have never met?

“He didn’t even want you to know about Jeanne,” my mother told me. “He thought you might think he compared you with her, and he didn’t. He simply saw the name as a sign of respect. He spoke to a priest about the matter, and the priest encouraged him to name you after her, provided he never compared you. ‘I would never do that,’ your father replied. I thought you should know. I didn’t want you to learn about her some other way. I thought you should hear about her from us.”

I hope my father never knew why I studied as hard as I did, why I researched the lives of the saints (I wanted a medal from a church), why I sat before my bedroom mirror with a notebook and documented my appearance and what exactly I needed to fix. I needed to be a smart, kind, beautiful daughter.

I tried not to hear her name when he said my own.

IX.

Salvador Dalí died from gastroenteritis at the age of one year and nine months. Nine months and ten days later, the artist Salvador Dalí was born.

“I deeply experienced the persistence of his presence as both a trauma—a kind of alienation of affections—and a sense of being outdone,” Dalí writes in his memoir, Maniac Eyeball: The Unspeakable Confessions of Salvador Dalí.

Dalí famously exaggerated the facts of his life, and yet as someone named after a dead child, I believe him when he says, “I lived through my death before living my life.”

He often recalled a childhood visit to his older brother’s grave, where his parents allegedly told him that he was their first son’s reincarnation. They kept in their bedroom, he claimed, a retouched photograph of the dead child. The “majestic picture,” he said, hung next to a reproduction of Velázquez’s painting of Christ’s crucifixion: “the Saviour whom Salvador had without question gone to in his angelic ascension conditioned in me an archetype born of four Salvadors who cadaverized me.” The four Salvadors: Dalí’s father, Dalí’s brother, Dalí, and Jesus (“savior” in Spanish translates to salvador). “The more so I turned into a mirror image of my dead brother.” Dalí felt his name transformed him into a lifeless skeleton.

In his 1963 painting Portrait of My Dead Brother, Dalí constructed a composite portrait of himself and his brother with a matrix of dark and light cherries, where the dark cherries form the dead Salvador and the light cherries the living one. His decision to merge his face with his brother’s reflects his father’s grief: “When he looked at me, he was seeing my double as much as myself. I was in his eyes but half of my person, one being too much.” Dalí depicted his brother as seven years old, an age his brother never reached. In his memoir, Dalí writes, “At the age of seven my brother died of meningitis, three years before I was born.”

Maybe he lied unintentionally at first, but later he still refused to admit that he was born nine months after his brother died. Even after Luis Romero published a book about Dalí, with Dalí’s help, that revealed when Dalí’s brother was born and died, Dalí maintained that his namesake had lived seven years. I can understand the psychological need for that distance. And I can understand Dalí’s need to merge the image of his face with that of his brother’s. When I painted myself in grade school, I pretended that I was painting Jeanne. I wanted to make myself Jeanne. I wanted to be her for my father. Of course Dalí needed to paint Portrait of My Dead Brother.

In the lower left corner of the painting, he reproduced the scene from Jean-François Millet’s painting The Angelus, in which a man and a woman recite a prayer over a basket of potatoes. A potato fork, sacks, and a wheelbarrow are strewn around them. In The Tragic Myth of Millet’s Angelus, his 1934 book devoted solely to The Angelus, Dalí argues that the peasant mother killed her son and anticipates being sodomized by her husband before she cannibalizes him.

When Millet completed the painting, in 1857, he painted a man and woman praying over a dark coffin-like shape. In 1859, after the American who commissioned the painting declined to take it, Millet painted a basket of potatoes over what Dalí insisted was a small coffin (a 1963 X-ray of the painting vaguely supports his argument).

Not all art historians agree about the coffin’s presence, but they do agree that Dalí’s inclusion of The Angelus in his own painting acts as a metaphor for his parents’ overwhelming grief for their firstborn.

“That painting by Millet,” van Gogh wrote to Theo about The Angelus, “that’s magnificent, that’s poetry.” Van Gogh reproduced the work in 1880 and titled the result The Angelus (after Millet). Did he see a connection between the incarnation and his own birth? Did he see a child’s coffin?

Neither van Gogh nor Dalí had children.

X.

Surrounding the ten-year anniversary of my father’s death, I stopped researching necronyms and started searching for details about Jeanne.

I found her childhood address and toured what had been her home. I interviewed one of her classmates and neighbors. I met one of her high-school friends.

“You look so much like Jeanne it takes my breath away,” her friend told me.

I learned that she had died March 2, 1961, twenty-three years and seven days before I was born.

The more I found out about Jeanne, the more I found myself slipping into some strange state. I lost control of my neck and arms and voice. I repeated, “Jeannie’s going to die. Jeanne’s dead.”

I contacted the cemetery where she was buried. I asked about the plot next to hers, if it still belonged to my father.

“Your father bought it, so it belongs to him,” the cemetery worker said.

“If he’s dead—” I began.

I said that my father chose to be buried in Ohio.

“Did he leave it to anyone in his will?”

“Not specifically,” I said. “He wanted everything of his to go to me.”

“Then it belongs to you.”

Next I visited her grave. There, on the gray granite headstone, was an engraved image of the Virgin Mary. The Virgin’s eyes looked down toward Jeanne’s name, which was almost obscured by leaves. The shadow of two blank maple trunks cut across the empty patch of land beside the grave—land that I now owned.

I called my mother. Without mentioning my trip to Jeanne’s hometown, I asked if my father had ever said anything more about Jeanne.

“When you were a little girl just learning to walk,” she said, “our neighbor Sheila calls me at the hospital. I was still working there, in medical records. Your father was at home with you. ‘Barbara,’ Sheila says, ‘you better get home. Terry is pacing around the backyard, weeping and holding Jeannie. He won’t put her down.’ So I went home and gently asked your dad what was happening. ‘It’s just a hard day,’ he said. That was in April or May. I took that to mean it was Jeanne’s birthday. You kept crying, but your father refused to put you down. He was terrified you would hurt yourself.”

The morning after that phone call, I was hospitalized for a “mixed dysphoric state with psychotic features.”

“Get into the ground, Jeannie” is what I heard.

“Stop,” I told the voices.

But to those around me, I was talking to air.

“My father died,” I explained to my doctors in the hospital.

Like the doctors before them, they asked: “When?”

“Ten years ago,” I said, “and I visited Jeanne’s grave on the ten-year anniversary of his death.”

“Jeanne?” they asked.

I tried to explain that I was named after a dead half sister. I tried to explain the letter i in my name. I felt hot tears running down my face. I was held at the hospital for a month.

Before my release, my doctors insisted I had to stop researching Jeanne, but stopping felt impossible. I returned to the hospital three more times.

For now, I am done with Jeanne.

Kristina Schellinski, a Jungian analyst and self-declared “replacement child,” writes in her 2009 article “Life After Death: The Replacement Child’s Search for Self” that guilt may arise from “the fact that the ‘I’ is not truly ‘I,’ that the replacement child is not free to live his or her own life, and may therefore feel a sense of guilt towards his or her own self realization.”

Is that why my father added an i to my name? To remind me that I was my own person?