He appeared as a guest on The Arsenio Hall Show in 1989. Seated rigidly on a purple sofa, the lights beating down, a little sweat forming on his forehead, he did not in any way appear to belong in such a place, more often than not reserved for athletes in the NBA or rap stars of high commercial visibility. A careful dresser, he wore a navy-blue worsted suit, a shirt with red candy stripes, a red necktie, and a white pocket-square. Onto his feet he had slipped a pair of two-tone red-and-white spectator shoes. He was seventy-nine years old, small and spry and bandy-legged. He had hair white as an empty page. Upon being introduced—“For over fifty-one years,” Arsenio Hall announced, “our next guest has published the wildest newspaper, I think, in the country”—Ben Thomas parted the curtains and stepped onto the stage as if from another century.

Although the studio audience applauded and whistled and, as they were prone to do on The Arsenio Hall Show, whoop-whooped, it was quite unlikely that many of those present, or watching on television, had ever heard of either Ben Thomas or his Evening Whirl, an eight-page weekly newspaper, a one-man operation, that had covered crime, scandal, and gossip in the black neighborhoods of St. Louis since 1938. Thomas looked a bit dazed, and throughout long portions of his conversation with Hall he maintained a wide, mute smile on his face.

To Thomas’s friends and relatives watching the show in St. Louis or in the studio, this performance by the editor might have been peculiar, if not exactly worrisome. It could simply have been a case of nerves. Or, seen in retrospect, it could have been the first symptoms of senile dementia, for within four years of Thomas’s television appearance, stories in the Evening Whirl would begin repeating themselves verbatim in back-to-back weeks, the names of cops would sometimes get confused with those of the perps, and finally, in 1995, Ben Thomas’s dotage would force his retirement.

But no one foresaw that now. Both on the page and in life, Ben Thomas had a domineering presence—he was a fearful disciplinarian with his sons and a taskmaster with his assistants. He commanded attention; he had the gift of authority. Possibly this characteristic had resulted from a professional five decades spent publishing a newspaper in which his voice alone prevailed. His editorial predilections ran toward such subjects as lovers’ quarrels gone homicidal, preachers who spent their free time pursuing sex on the St. Louis stroll, the 1970s heroin dealers who ruled over the housing projects in this border-state river town—not North, not South, not quite the Midwest—or any person who got on the editor’s bad side. He’d put your face on the front page.

Although the Evening Whirl covered crime and scandal in St. Louis, the word “covered” when applied to Thomas and his paper suffers from some imprecision. Concerning a territorial war between rival gangs in 1978, for instance, Ben Thomas wrote:

There is a rumor around the town

That one of three will be cut down

The Petty Brothers or Dennis Haymon

Will join the soap man, Mr. Sayman.The city wonders who it will be,

Just take it easy, you will see;

Guns will roar and rip like hell,

And how the Evening Whirl will sell.

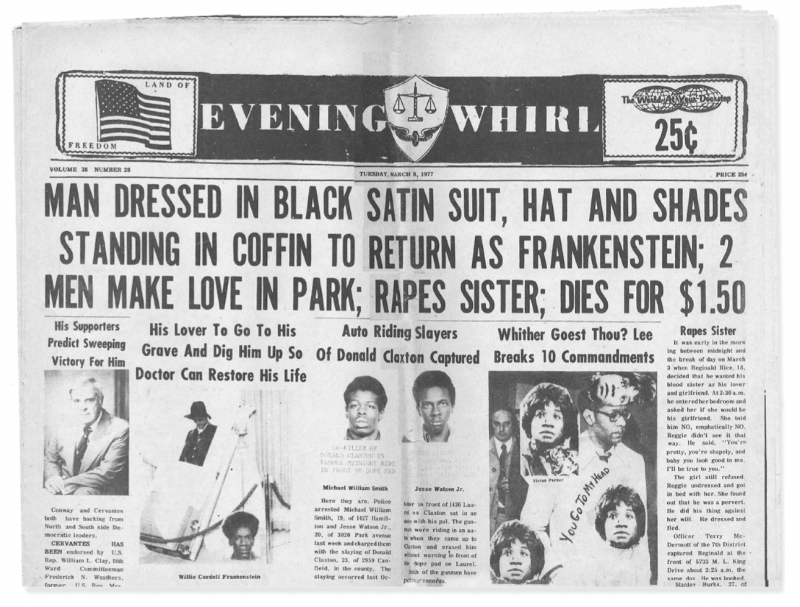

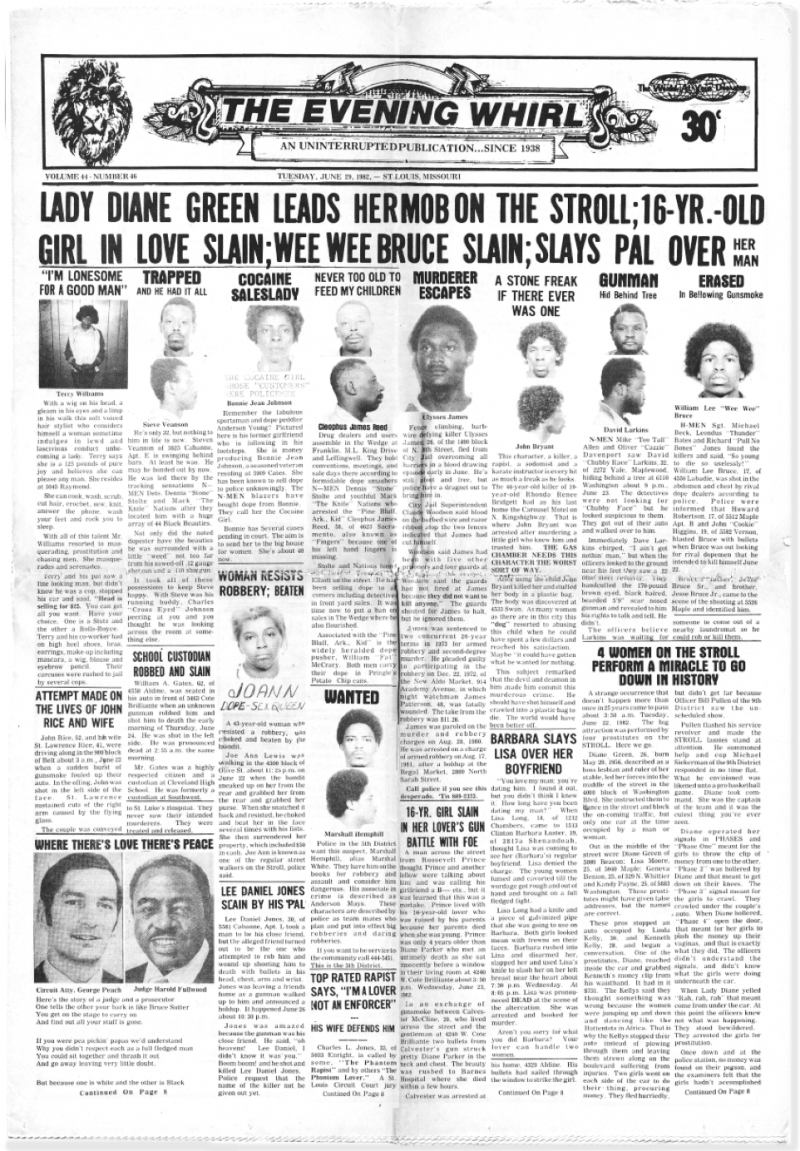

The Evening Whirl had a singular design—mug shots, both profile and obverse, were wainscoted two deep below the headlines. Pictures of the perps, Ben Thomas knew, sold newspapers. The faces were almost always black. Eight columns of triple-decker tombstones declaimed the week’s crimes and scandals, usually involving a killing, a cutting, a robbery, a rape, or some piece of local gossip. The lead story of nearly every edition was annexed with verse, built of four-line stanzas rhymed a-b-a-b. The meter of the lines approached the iambic. Headlines and pictures were sometimes cockeyed. Captions and advertisements were occasionally handwritten. With its shabby appearance and neighborhood scuttlebutt and atmosphere of danger, the Evening Whirl had the look and feel of an old, dark corner-saloon metamorphosed into a newspaper.

People likened Thomas to a Wild West newsman, an X-rated Walter Winchell, a blues lyricist. In later years he was also called an ancestor of gangsta rap. But he considered himself none of these things—in his own eyes he was a crusader against crime, an exposer of wrongdoing, and he had absolute confidence in the righteousness of every word that he wrote. His persona in print was that of a hanging judge; he thought of his paper as a public service. But the man also liked to sell newspapers. At its peak in the 1970s it had newsstand sales of 50,000. Thomas relied not on advertising but on circulation—the popular vote—and at a time when black business success came rarely, people around St. Louis referred to the editor as a “black millionaire.”

By the time Thomas came to Hall’s attention, however, the editor had entered the twilight of his career, and the health of the Whirl had begun to erode. Circulation had declined substantially. People had begun to think of the Whirl as a relic of another era, as a particularly offensive anachronism. Controversy and animosity had always surrounded the newspaper, and it arrived from two socioeconomic directions—from the criminals it brazenly attacked, and from the black bourgeoisie, whose sexual peccadilloes and petty connivings Thomas sought to expose whenever he could get the dish.

Nearly every issue of the Evening Whirl included lists of curious blurbs that appeared under the heads WHY and WHO. They were bits of crime news posited in the form of a question, as in:

WHY

didn’t Primus Oden, 18, of 3916 N. Florissant, pick up a gun and mow down the robber that invaded the P.M. Gas Wash at 3720 N. Kingshighway and robber the place of $250 cash? Make yourself valuable and useful.

and:

WHO

was the charming woman that had a flat tire in front of 1500 N. Union and was offered assistance by a stranger, and of course she accepted, but was fooled by the man who said, “Come and go with me to get a new tire,” and he then led her into an alley at gunpoint about midnight where he robbed her of $5, her watch and raped her too? A dog! Beware of strangers.

Thomas sprinkled these WHOs and WHYs throughout his pages. Readers ran across them like police-blotter Easter eggs. They implicitly articulated the theme of his publication, a theme that Thomas, in his Evening Whirl creed, stated in this way: “The Evening Whirl is a weekly newspaper dedicated to the exposure of crime and civic improvement. Our chief aim is to keep the public well informed of the interesting happenings in our community from week to week. Our aim will always be to help, but never to harm, and let the chips fall where they may regardless of class or culture or status in life.”

In his editorials Thomas expressed his opinions rather more bluntly. They read like apologias. He was responding to his critics. “We know that all good christians [sic] and decent citizens love the Whirl for its daring exposure of crime and attempt to lessen it by mere exposure. Our chief aim is to let the people know what is happening in St. Louis. We print the good and the bad news. That is what it takes to make a newspaper. Even a preacher doesn’t always preach about the good things in life. He tells you of the vice and varied types of crime happenings. Then he tells you how to live a decent life and serve God. The Whirl does exactly the same thing.” As time went on and his critics grew more vocal, Thomas’s apologias appeared more frequently, and followed an opposite course in delicacy. “The Whirl has preached PURITY and condemned CRIME. Those who don’t like it can kiss our behind.”

Over the course of his career Thomas survived Molotov-cocktail firebombings and drive-by shootings. He suffered libel suit claims amounting to millions of dollars and an attempted boycott of his newspaper organized by the president of the St. Louis chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. And yet, despite this constant flak, despite the vehemence of his opposition, Ben Thomas survived long enough to wind up on Arsenio Hall’s purple sofa.

I first heard of the Evening Whirl while a graduate student in creative writing at Washington University in St. Louis. A professor of mine named Charles Newman, a writer of elusive novels and a founder of TriQuarterly magazine, suggested the Whirl as a possible story idea. Among a handful of the university’s literary academics—most prominently William Gass—the Evening Whirl had long been a favorite. Gass even gave copies of the Whirl to visiting writers as a kind of going-away present. Evidently, Mario Vargas Llosa and Carlos Fuentes were particularly taken by Thomas and his paper. In Gass’s explanation, the Latin American writers, so attuned to the structures of race and economic class, found in the Whirl something familiar.

When Ben Thomas died in 2005, he left behind a body of work comprising some 3,000 editions of his newspaper and untold millions of words. It has all largely gone missing. Most African-American newspapers have been poorly collected, and, perhaps not surprisingly, the Evening Whirl has been collected more poorly than most. No library in St. Louis, university or municipal, owns even a single copy. Scattered issues lie here and there in scattered institutions around the country. The newspaper repository at the University of Texas at Austin, for example, owns precisely two copies. Howard University has an eighteen-month run from the mid-1970s with a four-month lacuna. But these are not hard copies; all are microfilmed, and many of the images are warped and whitewashed in the manner of poorly shot microfilm. Nonetheless, relative to any other library, the Howard collection is unequaled in its breadth.

But by far the largest number of Whirls amassed in one place belongs to a private archive. Stored inside three plastic mail crates, one stacked atop the other, they sit in a closet in the basement of a house in St. Louis not far from the boyhood home of T. S. Eliot. Anthony Sanders, the owner of the house and the current editor-in-chief of the Evening Whirl, uses the basement as his newsroom. Along with Barry and Kevin Thomas, the founder’s sons, who have lived in Southern California since their boyhood, Anthony Sanders took control of the Whirl in December 1995. A few months earlier, the Thomases had moved their father, deemed senile and incompetent, out of St. Louis for good. Despite his failing health, Thomas did not want to relinquish his throne. Under some duress, his sons brought him to California, where he had long owned vacation homes, first in the Mid-Wilshire district of Los Angeles, and then near the ocean in Laguna Beach—examples of what the Evening Whirl’s income could buy you. But these properties had lately been sold by the boys. And so, for the ten years between his retirement and his death at the age of ninety-five, Ben Thomas resided in the Los Angeles exurb of Valencia, first at Kevin’s place and then in a nursing home, while halfway across the continent his legacy moldered, as shopworn as its creator.

Shortly after arriving in St. Louis in the summer of 2000, I sought out Sanders, who escorted me into his basement and introduced me to the mail crates. The Whirl editions were yellow and fragrant with age. Brittle at the edges, they shed flakes like confetti, and after several hours spent parsing through the pages I had to wash my hands. Water from the faucet ran black with ink. The dates of the newspapers stretched from July 1971 up through Ben Thomas’s final days, with major gaps impeding the way. They constituted the disordered, incomplete record of a career, of a life.

*

He was born in 1910 in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, raised by maternal grandparents who were born into slavery, and educated in the early 1930s at Ohio State University, where he claimed he ran on the track team with Jesse Owens. (For the rest of his life he would ceaselessly tell stories of his exploits on the team with Owens, especially when in conversation with single women.) By the time he arrived in St. Louis in 1934 Thomas was already purged of his country-rube beginnings. As an undergraduate he worked as an OSU campus correspondent for a black weekly in Pittsburgh, and when he settled in his new city, he found a job at the St. Louis Argus, which in those Jim Crow times was the newspaper of record for the city’s black community. (The mainstream dailies, which wouldn’t hire black reporters in the first place, covered black neighborhoods only infrequently.)

Despite the Depression and Jim Crow, St. Louis hit its cultural apex in the 1930s. The Swing Era was in full sway, and Thomas became the Argus’s lead entertainment and music reporter, a post he held for a little over three years. Whenever big acts visited town—Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong—Thomas became part of each one’s entourage. For a brief time in the mid-1930s he dated Billie Holiday. His nickname was “The Baron,” which he often used in the Argus as his byline. Always entrepreneurial and trolling for new hustles (he was also a jazz and nightclub promoter) Thomas eventually decided to apply his talents to his own weekly publication. He titled it the Night Whirl, and for the first year of its life, in 1938, it covered music, nightlife, and local celebrity gossip—the social whirl of black St. Louis.

But less than a year later, Thomas caught wind of another kind of story that had nothing to do with jazz acts or club owners. Two high-school teachers had escorted a group of boys on a picnic to the country; pedophilia was the allegation. No other paper in town had the temerity to print the scoop. In 1991, Thomas conducted an interview with an archivist and oral historian from the University of Missouri-St. Louis. He recalled in his steady baritone, “So I changed the name from Night Whirl to Evening Whirl”—it was, the editor believed, a newsier title—“because right then and there I was through with amusement news… And sweetheart? I had no idea that they were gonna keep runnin’ me back to the press to print more papers. I put that paper out, and I went back to the press for the third time before I could satisfy Saint Louis. It’s been a crime sheet ever since.”

Thomas sold 50,000 copies of that first crime issue, at a nickel apiece, several orders of magnitude beyond his normal Night Whirl circulation. If he had wanted to make a dollar by hustling newspapers, this, Thomas discovered, was how.

*

Never simply a crime newspaper, the Whirl stuck close to its roots as a scandal and gossip sheet, and however adamant Thomas became in later years about his anti-crime crusade, he relied upon titillation as his most powerful newspaper-selling tool. Always economical, the resulting headlines told the entire story. They read like abstracts:

TEACHER PASSES OUT AFTER TORRID SEX WITH ANOTHER TEACHER IN MOTEL; SHE DRESSES AND LEAVES HIM; HIS WIFE COMES, GETS IN BED WITH HIM; HE AWAKES MAKING LOVE TO WIFE AND HAS HEART ATTACK

Almost always Thomas appended these tales with verse, often in the form of dramatic monologue:

Pearl there’s one thing I want you to know,

You’re nothing but a husband-stealing hoe;

Your ears may quiver and your hips may shiver,

If you have Max again I’ll throw you in the river.

Respectable burghers were Evening Whirl favorites. They were the success-stories of the black population, coveted examples of racial uplift, and yet Thomas attacked them anyway. The Whirl stood in complete opposition to one of the traditional and well-established projects of the mainstream black press—that is, to print whenever possible only the positive doings of the African-American community as a way to encourage its rise up the socioeconomic ladder.

For his part, Thomas felt he was being democratic. “The average man, be he a preacher, a schoolteacher, a doctor, a lawyer—whatever, they like to get out and get around sometimes,” he told a reporter from the Chicago Tribune in 1989. “And when they get caught, that’s when I cash in on them.”

In graphic, salacious detail Thomas chronicled scandals picked up from the police or whispered over the telephone by anonymous sources or confided over drinks in dark barrooms by trusted informers. Lawyers caught cuckolded, doctors who had sexually harassed their patients, churchmen busted by streetwalkers who suddenly presented badges, political leaders discovered to be homosexual—potential targets such as these would say prayers of mercy, and open that week’s Whirl with trembling hands.

In 1979, for instance, a lawyer was caught in flagrante delicto with another man’s wife:

PROMINENT ATTORNEY CAUGHT IN BED IN HOTEL WITH HIS LOVER

AS HER HUSBAND ENTERS WITH GUN, HE KNEELS AND PRAYS

Thomas spared no invective. He also seemed in awe.

Many women have described [the lawyer] as one of the sexiest sex-men his age. They say he deals heavily in sex. Many sex stories about the great lover have been revealed, but not printed. But this time an arrest and police report were in evidence.

The married couple of the story had evidently come upon hard times. The husband, who “had reasons to suspicion the fidelity of his wife,” trailed her and the lawyer to their hotel room and “smashed through the door like a football player on the Dallas Cowboys Football Team. And there they lay buck naked in the bed all absorbed in a love duel. Trysting time had come around and [the wife’s] paramour was functioning.” The occasion inspired seven stanzas. Thomas prefaced his verses by explaining that they were not his. Instead, they were part of an extemporaneous song sung by the wife while in bed with the lawyer. A portion of the poem read,

Daddy, oh daddy, I love your stroke,

You conjure my soul with every poke;

Love me this morning till the cows come home,

Carry on fool; you’re real gone.I’ll quit my husband if you quit your wife,

And be your woman the rest of my life;

I’m a good rocking mama night and day,

We will have only the devil to pay.

It was hard to tell, as the story went on, whether Thomas’s purpose was to condemn or defend the actions of the lawyer. Thomas concluded the article:

Since the door was smashed in and [the husband] was holding the nudists at bay with a gun, the hotel manager begged of him not to kill his wife and her lover of renown. [The husband] was staging a talk show and the lovers were forced to listen, look and keep still in their imposing pose that would tear any husband’s mind asunder. [The lawyer] was not allowed to plead this case. He was on trial. The judge was his woman’s husband….

[The lawyer] feels guilty of NOTHING. He realizes that he hasn’t broken The Ten Commandments. He did not covet his neighbor’s wife because they didn’t live in the same neighborhood. There is no law against two grown sexists fornicating. Millions do it every day. That includes preachers, teachers, business executives, nurses, lawyers, bankers, electricians, plumbers and laymen.

One cannot know, of course, whether Thomas achieved the pun of the story’s last word deliberately, but the result is nothing short of masterful. Like this particular attorney, Thomas felt guilty of nothing in printing such pieces, and his neighbors in St. Louis came to expect this. Around town people would often say to each other, as a kind of half-joking, good-luck good-bye, “All right, now, we don’t want to read about you in the Whirl.”

*

Though Thomas had an eye for the absurd and the comic, his voice in the Evening Whirl also contained heavy doses of anger. In the 1960s and ’70s, Thomas watched as poverty, drug addiction, and gangland violence increased in the black neighborhoods of his adopted hometown. The social whirl of St. Louis now involved more gunfights than jazz acts. Sixty percent of crimes committed in St. Louis in 1973 were perpetrated by blacks against other blacks. It all must have seemed particularly nasty to Thomas, who had reached retirement age, and whose memories of youth involved heavy nostalgia and idealization for that Jim Crow/Swing Era period of music, parties, and a tight-knit community supporting and insulating itself against the wider white world, with its subtle and not-so-subtle oppressions. Whatever the broader political and economic reasons behind the problems of the current moment, to Thomas it seemed as if the black community of St. Louis was responsible for destroying itself. His frustration set to boil, Thomas became consumed with outing the symptoms of the collapse—and he came to see this as his noble crusade, his life’s purpose.

Thomas’s anger was particularly evident when one of the last remaining gang lords of the 1970s, a man named Nathaniel Sledge, was murdered early in 1980. Thomas felt obliged to sum up the ’70s with a kind of retrospective:

The decade that ended December 31, 1979, was the bloodiest decade for, by and with blacks in the history of the city of St. Louis. Hundreds of black men and women died each year from 1970 to 1980 by the slashing and plunging blade or by the smoking bullets. It is a disgrace to our race to have so many murders within the race.

One might blame the white man for leaning toward segregation and discrimination, but he certainly doesn’t destroy our lives with bullets and knives. We are our own worst enemy. Even blacks slay more whites than whites slay blacks. We seem to be attuned to murder as a pastime.

Later in the piece, Thomas wrote that Sledge “went at it wholesale killing 2, 3, 4 and five at a time. Why did he remain free and never go to prison for these massive slayings?” Thomas responded to his own question by invoking the character of the Intimidated Witness. “Many known killers have gone free and scores of persons knew they were guilty. Their knowledge without application is fruitless and worthless.” It seemed as though Thomas had taken it upon himself to provide the service that intimidated witnesses wouldn’t—to take on, via the ink of the Evening Whirl, their collective civic duty.

In terms of newsstand sales, the Whirl didn’t really start gathering momentum until the 1950s. Not coincidentally, it was during that decade that the city’s black street gangs first developed a certain entrepreneurial élan. “Crimes were happening and reports of them appeared in the dailies in about 3 inches of space unless a white person was involved,” Thomas wrote in a short history of his career, printed in the Whirl in 1984. Coverage of black neighborhoods by the big mainstream newspapers virtually didn’t exist. And those African-American papers that were in operation, including the Argus, tried to avoid any news that might have cast a negative light on blacks. Thomas and his newspaper, therefore, filled the gap. By the 1970s, the circulation of the Evening Whirl reached its peak, estimated by Thomas’s sons at anywhere from 30,000 to 50,000 issues.

Among the reasons people bought the Evening Whirl was that it detailed the doings of the community’s most mythologized figures. Within their poverty-stricken confines, St. Louis’s black drug lords and career criminals achieved folk-hero status. And because the Evening Whirl told their stories over and over, and in such gutbucket style, Thomas played a major role in that mythmaking. A Whirl headline, 1972:

VICELORDS T.J. RUFFIN AND “FATS” WOODS TO RUN FOR MAYOR OF CITY

The story’s lead:

Two representatives of the underworld came to the Whirl Office by appointment Thursday evening at 5:30 p.m. very nattily dressed. They said they came to announce the entry of T.J. Ruffin, 47, of 3920 Beachwood, a ruthless gunman and killer deeply wedged in the heroin traffic, and the impossible “Fats” Little Al Capone Woods, 25, of Cass Avenue, as candidates for the mayor of St. Louis. Both said neither Cervantes nor Poelker [the city’s legitimate mayoral candidates] would have a chance at the lofty position. They reasoned that the two crime overlords had taken over the city anyway and were running it as they saw fit with a few cooperative police and their own men.

Even when he used satire to make a point, Thomas succeeded at the same time in creating antiheroes.

During the first half of the 1970s Thomas directed much of his rage—and myth-forging influence—at a group of heroin dealers led by James Harold “Fats” Woods and Earl Williams Jr. Based in an apartment located several blocks from the massive Pruitt-Igoe housing project (perhaps the worst public-housing fiasco in the history of HUD), Woods and his group were arguably the city’s most powerful black gangsters of any decade. Earl Williams served as the gang’s lead assassin. Between 1970 and 1973, he beat murder raps on three separate occasions. Over the previous decade he had collected a total of twenty-six arrests. A jury had yet to convict him. In the fashion of the day, he wore wide-brim hats and jawbone-length sideburns. He had learned his trade with a high-caliber rifle as a Marine Corps sniper in Vietnam, but for his work stateside he preferred, a bit self-indulgently, sawed-off shotguns. He lived on the first floor of a high rise in Pruitt-Igoe, but in order to reach him, and offer one’s regards, it was necessary to pass through a platoon of armed sentinels. He had ensconced himself in the projects like a nazir in his tents.

Enraged by Earl Williams’s ability to beat the rap, Thomas published this headline in August 1970: COMMITTED MURDER 3 WEEKS AGO; COMMITS ANOTHER AND HE WALKS THE STREETS FREE. He led the article by saying, “If I, Benjamin Thomas, were to be a judge in the circuit courts of St. Louis I would retire in shame.” He went on to relate how authorities had released Williams for lack of evidence despite the fact that the hit man had shot two of his rivals to death. “This newspaper viciously condemns such court action and suggests that our court system be abolished and replaced with a court of honor that would protect the innocent and the worthy citizens who detest crime. I hope I am elected to the State Legislature. I will do something about this horrible situation and do it fast for the safety of decent human beings.” The editor noted that 282 people were murdered in St. Louis in 1969, and that in 1970 so far 161 had met the same fate. “The year,” he wrote portentously, “is only half gone.”

Thomas did indeed run for Missouri state representative, in 1970, with crime curtailment and gun control constituting the whole of his platform. He made sure to play up his Evening Whirl credentials, not that he needed to. The name recognition was built-in. Ultimately, though, his campaign failed; he lost in the Democratic primary by a wide margin. The incumbent, a woman named DeVerne Lee Calloway—the first black woman to hold elected office in Missouri—focused not on crime but on liberal welfare reform. She went on to a fifth term in the House. Thomas the politician was unable to compel the electorate as well as his newspaper could compel his readership. When separated from the pages of the Evening Whirl, his message lost a good portion of its power. Though he never again stumped for office, though he never again took the podium to deliver an anticrime harangue, each week in the Evening Whirl Ben Thomas continued to preach his gospel.

*

At the Delmonico Diner, on Delmar Boulevard in North St. Louis, a coterie of Baptist ministers gathers each morning before work. They eat breakfast, read through the local papers, and conduct heated political debates, exercising their wits in preparation for Sundays at the pulpit.

One cold December morning before Thomas died, I arrived at the Delmonico to discuss the Evening Whirl with two preachers: the Reverend Earl Nance Jr., the head of the St. Louis Clergy Coalition and pastor of the Greater Mount Carmel Baptist Church, and the Reverend E.G. Shields Sr., pastor of the Mt. Beulah M.B. Church, another big local congregation. With jokes and handshakes, the preachers greeted almost every other diner at the Delmonico. After a leisurely interval, they sat down. Men still desiring an audience walked over to the table and lowered themselves to whisper into the preachers’ ears. Examining the day’s Post-Dispatch, Shields and Nance dissected the latest Jesse Jackson scandal, in which Jackson had admitted to fathering a child out of wedlock, but soon, and more than a little appropriately, the preachers’ conversation turned to Ben Thomas and his Evening Whirl.

“I don’t think you’ll find too many ministers who will admit to reading the Whirl on a regular basis,” Rev. Shields said. “It was a scandal sheet. Ben was always looking to put something about ministers on the front page.”

This was an understatement. Aside from murderers and maybe hookers, stories on wayward preachers amounted to the Whirl’s most fertile genre. Everywhere in St. Louis, it seemed, “prayermen” were cultivating harems or fleecing the faithful with healing roots or instigating with their “dictatorial” ways “unglorious battles” with their congregations. There was the clergyman who had acquired four wives, and, in defense of his polygamy, was quoted by the Whirl in a monologue: “All of us are God’s chillun, and we can marry as much as we want to… When I moved out it was the next sucker’s job to take over, ’cause he’d be the one sleeping with her and enjoying her.” There was the pastor who, according to a 1984 Evening Whirl headline, begged MOTHER AND DAUGHTER TO BE HIS BABES; HE ASKS THEM TO INDULGE IN ORAL SEX; HE’S JAILED. The pastor was quoted as saying to the daughter, “If I have to put you to sleep to make love to you, I will do so. Do you know how to put lipstick on my dipstick? Amen! Glory! Now you have heard my story.” There was the preacher who allegedly beat his children with “tree limbs and electric cords,” and who, Thomas continued, “badly needs his own ass whipped until he can’t sit down on it on a pillow without crying like a baby and meowing like a pussy cat.” There was the “renown” reverend who had allocated $17,000 a year to his gay lover out of the congregation’s tithings. “He is like a hound dog after and with this man whom he describes as his husband and wife and thrill of his life.”

Not surprisingly, preachers around town grew ever more wary, and weary, of Ben Thomas’s scribblings. The Reverend Nance said, “Oh yeah, they printed rumors. Preachers were always feeling the heat from that kind of thing.”

The Reverend Shields said, “Between the both of us, we knew any number of ministers who were written up in the Whirl. I was kind of glad when he stepped down.”

(Neither Nance nor Shields ever saw their faces on the front page of the Whirl, it bears remarking.)

Though the Whirl’s preacher reports undoubtedly grew out of Thomas’s desire to attack the hypocrisy of the serially sinning cleric, the editor also seemed to have a preternatural compulsion to undermine the provinces of power, wherever they existed. The church was (and arguably still is) the most influential institution in black America, and had been since before the Civil War. Hundreds of churches did business in St. Louis, and for Thomas they were, on the whole, just that—commercial enterprises masquerading as spiritual. Obviously Thomas had no problem with commerce; it was the masquerade he attacked. Wherever a minister abused his station, whenever he drove around town in a fancy car or enticed young women with his congregational pay stub or lorded over the laity with an iron fist, Thomas was there to report it, substantiated or not. More than once an irate minister sued the Whirl for libel, and more than once the Whirl lost.

The money Thomas made by printing these stories mitigated the occasional legal obstacle. Indeed, as with all of Thomas’s journalistic endeavors, his true motivations were ambiguous, for he waged his crusade against the city’s profligate clergy for reasons of cash flow as much as principle. Like copy on gangsters, accusatory headlines about churchmen sold newspapers, and sold them fast. Both gangsters and preachers, at least when they appeared in the pages of the Evening Whirl, were exploiting a class of the vulnerable—poverty-stricken addicts in the one case, the poor devout in the other. Barry Thomas says of his father, “Even if preachers were quote-unquote good or honest, that a preacher would ask for money—it looked dishonest to my father. He’d say, ‘Why take money from poor people?’ And then you’d see preachers driving around in big Cadillacs while all of their members were destitute.”

As the Reverends Nance and Shields discussed Ben Thomas at the Delmonico, a man walked into the restaurant. He was older, perhaps in his early seventies, tall and broad-shouldered, with graying hair and a thin mustache. After a round of hearty good-humored greetings with Shields, Nance and almost everyone else in the restaurant, he sat down at the table and removed his leather gloves. Without a word passing between him and the wait staff, food appeared in front of him. Nance apprised the newcomer of the discussion at hand. Instantly the man’s face changed shape.

“The Evening Whirl! That was the dirtiest, lousiest evidence of lies about the truth about a people I’d ever seen! What angered me about it, you could find it in Clayton.”

The man’s name was James F. DeClue; Clayton was an affluent, mostly white suburb of St. Louis, where for decades a local newsstand had sold the Evening Whirl. DeClue sketched a hypothetical scene. A white father, on his way home from work, buys the Whirl at the Clayton vendor, and later that evening his kids get hold of it. They spread the paper wide across the dinner table for a gander at the doings of the black race in St. Louis. Mug shots among the brussels sprouts. “Children’s minds would be infected with the idea that this is how these people live,” DeClue said. “But nobody would fight him. It must’ve been some kind of mob hook up.”

In the mid-1980s James F. DeClue was pastor of the Washington Tabernacle Baptist Church, for years the most important black church in the city. During the same period he was also president of the St. Louis chapter of the NAACP. Sometime during his tenure there, DeClue became fed up with Ben Thomas and the Evening Whirl, and in his capacity as president, he took the extraordinary step of attempting to organize a boycott of the newspaper. The seriousness of this is not to be underplayed, for according to NAACP rules, any boycott of a business requires the permission of the national office, in Baltimore. DeClue’s gambit, however, never made it that far.

“Mostly I was just trying to find someone who would join me in a fight against him and his paper,” DeClue said. “I tried to convince my members to boycott it, to not buy it. I wasn’t successful. For one thing, it was a popular magazine, and the level of pride in the community was such that they didn’t think it was a problem. No matter whom we talked to, groups of ministers, businessmen, there seemed to be some kind of fear. Maybe they were afraid they’d end up in it.”

“What’s the saying?” Rev. Nance said. “‘Don’t get into a brick fight with the man who owns the brickyard’? Or, ‘Don’t hit the king unless you can kill him.’”

*

On the concrete driveway of a suburban house in Southern California, a ninety-year-old man stood with his hands behind his back, surveying the scene. The day was bright and dry and warm, November 2001. Hills the color of khaki loomed in three directions. In their arid crooks and gorges, at about the time of Ben Thomas’s birth, Cecil B. DeMille had staged his Westerns. But now, two superhighways, the 5 and the 210, coursed through the canyons like paved-over riverbeds, and rising above the valley’s racket of corporate parks and shopping malls and palm trees tall as freeway street lamps, vast neighborhoods—stucco, Spanish tile—were cambered to fit the hills. This was Valencia, set down and let loose in the once-wild chaparral of the Santa Clarita Valley, about forty miles north of downtown Los Angeles.

“Right now,” Ben Thomas said, “if you asked me what city I was in, I’d be guessing.”

“Take a guess,” said Barry Thomas, who stood beside him.

“I lived in Columbus once. Am I in Ohio?”

“You’re in California.”

“California! Well. I wouldn’t have guessed that.”

Earlier that morning Thomas had dressed carefully in 1970s chic: brown polyester trousers, a silk shirt with wide purple stripes over a red turtleneck sweater, burgundy patent-leather shoes. His eyes were still intense, their color extraordinary—deep brown surrounded by a band of cobalt blue. Photographs of Thomas taken just five years earlier showed a man with broad shoulders and an almost corpulent face. Now, his ankles and wrists were bone thin and he weighed only 145 pounds. Still, considering his age and despite his frailty, Thomas moved nimbly. He looked athletic and fit, a little huggable man.

In Valencia, Thomas was not altogether aware of what status he had with regard to the Evening Whirl. A pencil always peeked out of his breast pocket. In explanation, he responded, “Well, I’m a newspaperman.” Sometimes he believed he was on short-term leave, and that he’d would soon be back making the rounds at police headquarters. At other moments the old vitriol over his contentious retirement would loosen his synapses. Once, informed of the paper’s new ownership, Thomas, his voice pitched with disgust, said, “When I get back to Saint Louis, I’m going to clear out the entire staff.” He was reminded that he had retired and therefore had no staff.

“Well, I’ll come out of retirement then! No one can stop me. I own that paper. I can do anything I want. There’s not one person alive,” he said, holding his thumb and forefinger a quarter inch apart, “who owns this much of that paper!”

In Thomas’s bedroom at his son’s house, old photographs covered the tops of a dresser and a bookshelf—an ornate photo-biographical collage. More than half were pictures of girlfriends. The shelf also held a half dozen spiral notebooks and yellow legal pads. Out of them stuck envelopes, scraps of paper, dog-eared pages. They contained hundreds of poems, all of which Thomas had composed since his move to California: “Lonesome,” “Puzzled,” “Forever,” “Whenever,” “On the Ball,” “Get Up and On the Go,” “Day and Night,” “I Am Ready,” “Screaming In My Sleep.” Thomas would sometimes take a notebook, seclude himself in his room, and write for hours. One poem, called “Confused,” has this last stanza:

Nothing special was on my mind.

Was there something I had left behind?

Somehow I twisted and I turned,

The more I did it, the more I burned.

In July 1995, in a wood-paneled auditorium at Washington University, the Greater St. Louis Association of Black Journalists convened its annual Hall of Fame awards ceremony. The headlining inductee was Benjamin Thomas. Three months later he would be in California, never to return to St. Louis. Needless to say, it came as a surprise to many that the Evening Whirl had, in the year of its editor’s retirement, received this tribute from its peers, especially from a group as archly mainstream as the Association of Black Journalists. It was co-founded by Gerald Boyd, a former St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter and—until it was discovered that Jayson Blair had burned his master’s house by composing some dubious copy of his own—the managing editor of the New York Times. A debate within the association’s board had preceded its decision to induct Thomas. Gregory Freeman, a columnist for the Post-Dispatch and a member of the board, explained to me, “The question we asked was, ‘Is this journalism? Is this something we should be honoring?’ Ultimately this guy has been around since 1938. At one time it was the best-read black weekly in Saint Louis. And in that sense, he was deserving of the award.”

At the ceremony, Gregory Freeman introduced Thomas with perhaps five minutes of remarks, after which the editor slowly ambled to the podium. He accepted his Hall of Fame prize and turned to meet the camera flashes. The crowd applauded—some people stood, some did not—and when Ben Thomas returned to his chair to watch the rest of the night’s presentation, he fell asleep.