Orangutan: 97% human

I was driving with a friend once and he said, out of the blue and in a fake German accent, “Ze hairy orung-gootunga, ze old man of ze woods.” My sense is that a month does not go by in my life when I don’t think of this and laugh out loud. Whenever I see any kind of primate, orangutan or not, I say the same line in the same accent, out loud more often than not. Not only do people not laugh; they do not smile. Thus I have spent many years sharing a private joke: not with the friend whose joke it was (years after he first said it I had the opportunity to say it back to him, and he, too, looked at me blankly), but with the orangutan himself. I like the notion of an old man of the woods. In the manner in which, as humans, we cultivate feeling toward things through the lens of how they make us feel about ourselves, this joke makes me feel warmly toward orangutans.

Recently I took my child to the zoo. Just as I prop up my shoddy environmentalism by driving my household recycling like a surly ringmaster, I prop up my shoddy knowledge of and concern for the kingdom Animalia by disliking zoos. The zoo we went to is considered a fine one by world standards. This means a lot of things—it’s shady, well kept, quiet, and expansive—but in a basic sense it means this zoo has put enough money into landscaping to allow visitors to suspend anxiety about the one immutable fact about zoos: they’re prisons.

We saw the lions—when I was a child, a deranged martial arts expert stole into the enclosure at night and tried to take on the king of the jungle—and we saw the tigers, pacing back and forth in a manner that brought to mind a martial-arts expert immediately prior to taking on the king of the jungle. Do tigers pace in the wild? Wouldn’t they sleep, scan the horizon, or run full tilt at their dinner? We had butterflies land on our shoulders in a vast biodome-like structure. We saw giraffes, who apparently never sit down, and elephants, who are pregnant for two years.

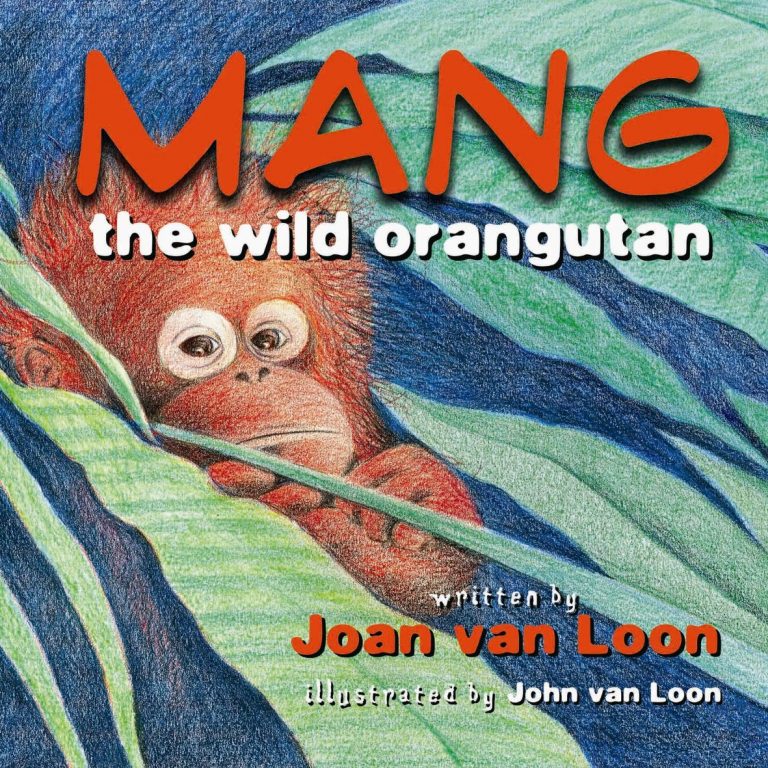

Then we came to the orangutan enclosure. It is thrilling. It is, in the strangest possible way, a view of oneself. It is like looking in the mirror with an...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in