I. GENTLE FOLK

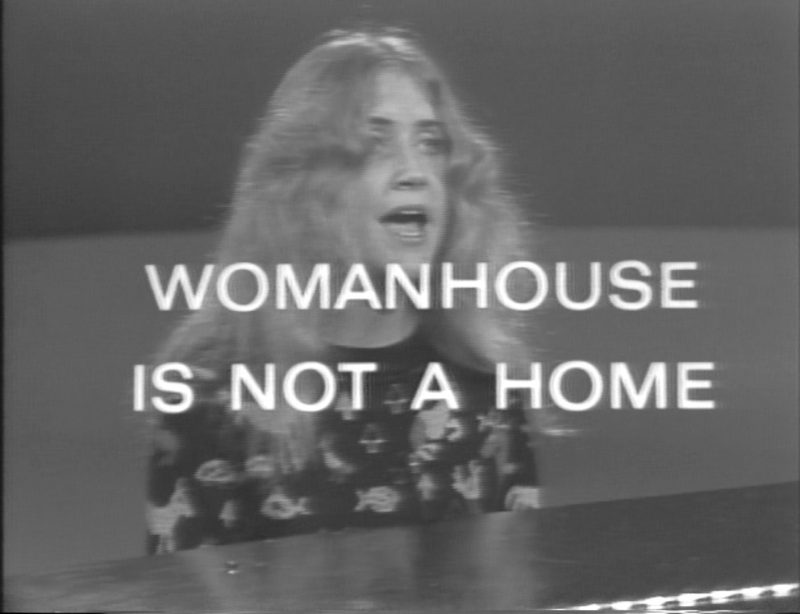

A young woman wearing high-waisted jeans and a sweater patterned with jumping reindeer, a quintessentially 1970s folk singer, accompanies herself on a grand piano. “You try so hard to tame me,” she croons in a gentle voice, “so the preacher can rename me / and then put me on a shelf.” Her performance opens Womanhouse Is Not a Home, a documentary that aired on Los Angeles public television in 1972. The film was produced and directed by thirty-year-old Lynne Littman (though the film erroneously credits Parke Perine as director), one of a handful of women working in television production at the time, and its subject was an unusual art installation called Womanhouse. Executed by a group of young art students and two renegade professors in a derelict mansion in Hollywood, Womanhouse was a first among firsts—the first exhibition of self-identified feminist art in the country, and the inaugural project of the first-ever university-sponsored feminist-art program. Feminist art in 1972 was an avant-garde, fringe movement; several members of Littman’s crew found the material disturbing enough that they asked that their names be removed from the film’s credits.

The stars of Littman’s film, however—the young female artists who made Womanhouse—strike the viewer as more winsome-naïf than threatening-militant. They may be the representatives of a major social movement, but they also titter and smile, reclining personably on pillows to chat. They marvel on camera at beginning a life that promises to be different than that of their mothers, at having become artists, at being interviewed for television. The novelty and self-consciousness of their feminism are unmistakable. Littman’s subjects are the antitheses of the bra-burning militants who populate much of our historical memory of feminism. They are gentle and tentative where the stereotype is dogged and strident, vulnerable where the stereotype is severe. Robbin Schiff, for instance, pauses and stumbles over her words. “I really do feel that the things I want to show are valid,” she tells her interviewer. “The scariness, the fear, the pain that I want to make in my art is valid, and it doesn’t have to be aesthetically pleasing.” However jaded by feminism contemporary viewers might be, it’s impossible not to feel the quaint charm of this young woman coming into her own.

Littman’s film is ostensibly a documentary about Womanhouse, but it also captures an Edenic moment in the history of feminism and feminist art, and a moment when the two were inextricably intertwined. The definition of feminist art was art that evinced feminism, and to practice feminism was to be an artist of sorts—to speak honestly from one’s own perspective. “Good” art was inspired by feminist principles and should inspire the same in viewers, while “bad” art was the result of a reluctant or ambivalent feminism. For better and for worse, Littman’s subjects were artists and feminists in the same stroke. Their art was only as strong as their politics, and their politics were the reason to make art.

II. POWER COUPLE

The Feminist Art Program was established at CalArts in Valencia, California, a newly minted school founded at Walt Disney’s dying bequest, co-led by artists Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago. Schapiro was the older and more accomplished artist of the pair; her work was represented by the well-respected New York art dealer André Emmerich, and she’d been teaching at CalArts a year before launching the program. (Her husband, the artist Paul Brach, was CalArts’ dean of visual arts.) Chicago’s political stance was more aggressive than Schapiro’s: born Judith Cohen, she took the name Gerowitz from her first husband, and then, seven years later, legally changed her name to Judy Chicago, in reference to the city in which she was born and raised. She announced the name change and a solo show, in 1970 at California State University at Fullerton, with two full-page ads in Artforum. The first proclaimed: “Judy Gerowitz hereby divests herself of all names imposed upon her through male social dominance.” She struck through the word Man in One Man Show and wrote Woman. The second was a photograph of Chicago with a butch haircut and a cocky expression, poised against the ropes of a boxing ring.

Schapiro and Chicago inhabited the same Southern California artist circles, and their rapport developed through an appreciation for each other’s work. During a trip to San Diego in 1968, Chicago visited Schapiro’s studio and saw Big Ox No. 2, a painting of a red-and-pink O superimposed over a red-and-pink X, which Chicago says she immediately understood as an attempt to engage with feminism using the language of abstraction. In turn, Schapiro praised Chicago’s Pasadena Lifesavers, a series of doughnut shapes in pastel-colored spray paint on acrylic. (The average viewer wouldn’t have made the connection between these images and their political subtext, but feminist insiders knew otherwise.) Schapiro brought her CalArts class to see Chicago’s 1970 exhibit at Fullerton, and Chicago invited Schapiro as a guest lecturer to her feminist-art classes at Fresno State University. Schapiro was inspired by Chicago’s intense energy, and convinced her to leave Fresno and move to CalArts, where the two women would direct a feminist-art program together. The program launched in the fall of 1971 with twenty-one students, including a contingent that followed Chicago from Fresno.

At the time, CalArts was a bastion of alternative art practice that had quickly strayed from the conservative ethos of the Disney family. The faculty included Allan Kaprow, inventor of the “happening,” as well as sitar virtuoso Ravi Shankar. The art practice of professor Wolfgang Stoerchle involved extracting miniature Disney figurines from his foreskin, and Fluxus artist Alison Knowles dropped reams of her poetry on the school from a helicopter. The critical-studies program, a safe haven for draft dodgers and underground-zine editors, began its first session with a communal chant of “om.” Faculty stripped at a trustee meeting to show support for students’ right to swim nude in the campus pool. In this spirit of bohemian welcome (rather than endorsement of any specific principle), CalArts agreed to underwrite the nation’s first institutionalized foray into feminist art.

The school also acquiesced to Schapiro and Chicago’s first major initiative, which was to move the program off-campus. Both instructors were convinced of the inhospitality of the art world to women, and felt their students needed a protected, females-only place to work. The move also aligned the program with the broader feminist movement, which was exploring female separatism. Dean Paul Brach approved, boasting that the female-separatist plan “freaks all the liberals around here in exactly the same way other liberals were freaked by the black power thing.” Thus, for their curriculum’s exploration of the idea of “home”—a topic central to feminist ideology in the early 1970s—Schapiro and Chicago found an abandoned mansion in which to work, nearly an hour’s drive from the university.

III. HAUNTED HOUSE

The house was a dilapidated seventeen-room estate scheduled for demolition, and leased to CalArts on a short-term arrangement by a sympathetic landlord. Students in the Feminist Art Program spent most of their time there, working assiduously to develop the indoor and outdoor spaces into a series of site-specific artworks. Each room was designed as a response to the psychic connotations of that specific domestic space. The kitchen represented nourishment and resentment, the bathrooms engaged with privacy and taboo, the bedrooms trafficked in beauty and inadequacy. Visitors toured the exhibition—up a grand staircase, through the kitchen, the pantry, the bedrooms, parlors, and closets—as if they were exploring a crime scene or a haunted house, peeking in on the sordid remnants of a deranged homemaker.

Littman’s documentary, which has gone virtually unseen since its initial airing (but recently became available when the Academy Film Archive in Los Angeles accessioned Littman’s collected works), features all of the most notorious rooms of the house. Littman films the Menstruation Bathroom, seen only through a gauze scrim and stocked with boxes and boxes of vaginal deodorizing sprays and douches; a garbage bin in the center of the room overflows with bloody tampons. The Bridal Staircase entailed two mannequin brides, one white and lovely at the top of a grand staircase, and another at the bottom, pitched forward and crashing into a wall, her wedding dress muddy and tattered. A nursery with oversize toys is scaled to make adults feel like children. A sculpture of a woman molded in colored sand reclines in a bathtub; visitors touch the effigy until it crumbles into a shapeless mound. The psychedelic Womb Room is festooned with loops of crocheted rope and doily-like panels, while the Lipstick Bathroom is strewn with underwear and two hundred tubes of lipstick, the fur-covered sink littered with toiletries. Upstairs, in homage to Colette’s 1920 novel Chéri, a bedroom has been converted into a courtesan’s boudoir. Acting in the role of Colette’s protagonist, Lea, an older woman spurned by her much younger lover, student Karen LeCocq sits at the dressing table ritualistically applying and removing a great deal of makeup—a performance that, according to the organizers, brought many older viewers to tears. In the linen closet stands a decapitated mannequin, her head set on a shelf.

In Littman’s documentary, the Womanhouse kitchen is particularly memorable. (“I love the eggs turning into tits!” a visitor in the film exclaims.) Climbing up the walls are yellow-and-white fried eggs sculpted of foam; overhead, they morph into candy-pink pseudo breasts. Art tends to present this kind of kitsch through an ironic lens, but as an extended scene with the artist responsible for the egg-breasts shows, there is no irony intended here. The artist, an effusive woman named Vicky Hodgett, stands in the kitchen and uses her index finger to depress a nipple. She smiles and watches the breast expand back to its original shape. She does it again, and then again. She continues fingering the breasts as she explains the process of creating the Nurturant Kitchen:

When the time came to put [the breasts and eggs] in the room, it was just an incredible thing. I had them all in boxes. I had like fifty breasts in a box. They were just really beautiful. I brought them in and we started to put them up on the ceiling—started with the eggs—and as these eggs started making their rounds on the ceiling, they got pinker and pinker, and then they blossom little nipples and they start getting really pink and coming down the walls… and I got so excited! These breasts were there and it was really a very incredible experience. It was the first time I’d ever done a really big work of art and it wasn’t at all what I expected to do.

Not only the egg-breasts but the entire kitchen—dishes, utensils, cupboards, stove—is lacquered in pink, a color dubiously chosen, artist Robin Weltsch explains, “to represent women and skin and the body of a woman, because I felt the woman was the feeder of the home.” (All of the Womanhouse artists were white.) In the adjacent pantry hangs a suite of everyday kitchen aprons turned into bizarre costumes, the most disconcerting of which features rows of pendulous breasts.

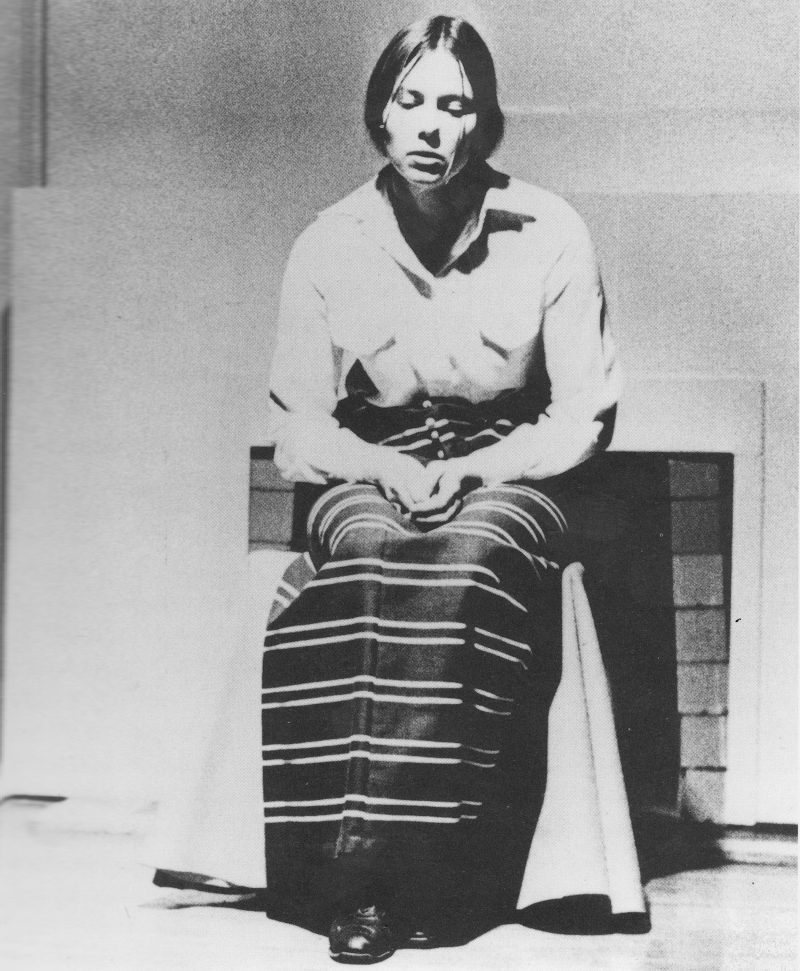

The living room was reserved for the performances that were scheduled throughout the exhibition and that are documented in Littman’s film. A woman in a dowdy housedress and slippers irons a sheet in real time. A group of six women mimes the birthing process, moaning, “Pu-u-u-u-ush!” as they give birth to each other through a tunnel created with their legs. In Waiting, a hunched woman rocks miserably back and forth, recounting her entire life as a sequence of things for which she passively waited. The most outré performance of the lot, Cock and Cunt, stars two characters, He and She, each wearing oversize plush genital prosthetics, which they wave around as they converse. At one point, He cradles his gigantic penis and says, “A cock means you don’t wash dishes. A cunt means you wash dishes.” She inspects the pink fabric strapped to her waist and says with wonder, “I don’t see where it says that on my cunt.” The piece ends when She requests the right to sexual pleasure and in response He uses his penis to violently thump her over the head.

IV. BOOT CAMP

Schapiro and Chicago were determined to create not only new forms of art and new standards for judging art but also new methods of teaching artists. Borrowing from the feminist tradition of consciousness-raising, or “C-R,” Schapiro and Chicago conducted their classes in a circle, sitting on the ground. There were no art materials in sight, and only a few rules: each participant could speak for an equal amount of time, uninterrupted; women should support each other by gentle touches and close attention; shared information never left the group. Schapiro and Chicago led their students in gut-wrenching group conversations about ambition, sex, mothers, money, and rape. Tears and furious accusations were routine—one student described the classes as “guerilla theater”—and emotional catharsis was expected, if not required.

Artwork was never discussed apart from the feelings it sought to express, and critiquing a work of art became tantamount to attacking the person who made it. A flawed artwork was nearly the same as a flawed feminism, and a flawed feminism was the result of a woman refusing to admit the extent to which she’d been harmed by misogyny. Convinced that intense emotion produced the best art, Schapiro and Chicago became experts at provocation. When their students became uncomfortable and angry, they took it as proof that their method was working.

The tumult of this teaching style was compounded by the sheer amount of labor required to renovate a derelict mansion in a few weeks, a kind of labor with which the students had little or no experience, as well as the growing difficulty in the professors’ relationship with each other. (Schapiro and Chicago weren’t on speaking terms for most of the following year.) Though C-R was designed to support women’s emotional realities, in this tinderbox situation it dredged up gendered clichés: students and professors traded accusations of acting “hysterical” and “unreasonable”; professors claimed the students’ rage was really about their own mothers; students said the professors’ rancor with the art world was really about their own failures; they blamed each other for wasting time with unenlightened men.

Chicago in particular provoked a great deal of distress. If a student’s phone line was busy, she asked the operator to use the “emergency interrupt” function, even for casual calls. She questioned the students’ relationships with their fathers, boyfriends, and husbands, and interrogated women who claimed to be on good terms with their mothers. In acceptance interviews, she asked if applicants were willing to give up makeup. She could be counted on to respond favorably if a woman complained about her (hetero) sex life. She told Suzanne Lacy, a student in the program who also had a fledgling career as a psychologist, that if Lacy didn’t set aside her pursuits in other fields, Chicago would refuse to work with her. (Lacy was, she later reported, grateful for the ultimatum.) Chicago threw a wine bottle across the room during a student critique. The dilapidated house in which the women worked had no electricity, heat, or working toilets; Chicago considered it an excellent opportunity to toughen up the young women and required them all to purchase work boots. Rumors persist that she locked students inside their studios. Women in the program called it “boot camp for feminists.”

Paula Harper, a CalArts art historian who was on the program faculty, noted that rather than teach students to make art, Chicago saw her role as forcing women to develop the personalities of art makers, a process Chicago called “personality reconstruction.” (Two decades after Womanhouse, her language hadn’t softened: “Dealing with young women,” she said in 1993, “means doing remedial education.”) Her students, she judged, had adopted the passive personalities expected of ladies, not of serious artists. Artists, Chicago said, needed to be “active, aggressive, self-expressive, self-valuing, with a secure sexual, artistic, and historical identity,” and a lady was none of those things.

Schapiro and Chicago took pains to create an environment in which women could express their true selves, but they also maintained a militant preoccupation with directing the shape of that true self. Like much of second-wave feminism, they were caught in a paradox: feminism was born from the authentic experiences of women, and yet some experiences, like enjoying lipstick, Western philosophy, or the missionary position, weren’t authentic enough to qualify as feminist.

V. DOUGHNUTS, HOLES, AND GASHES

Aside from Schapiro and Chicago, just three CalArts professors made an appearance at the opening of Womanhouse, and two of them were married to the organizers. But in time, the project became the subject of major press reviews, features in Time, and Ms., and Littman’s television documentary as well as a second film by the artist Johanna Demetrakas. The organizers claimed that ten thousand visitors toured the one-month installation; Time put the number at closer to four thousand. Even that lower estimate is remarkable, given that the exhibition took place outside a gallery or museum and largely comprised the work of students. Visitors came to gape, admire, and disapprove; Womanhouse animated the era’s arguments about domestic politics. But despite the mainstream attention, or perhaps because of it, Womanhouse occupies a tenuous place in twentieth-century art history, championed by a small contingent of feminist-art historians and ignored by nearly everyone else.

As a one-time event involving exclusively female artists making genre-bending work composed of nontraditional materials, the project doesn’t fit neatly within the usual narrative of contemporary art. The art world tends to canonize permanent works by a single artist in a distinct medium. The didactic theme, the crude symbology, and the heavy-handed use of feminine kitsch also set Womanhouse apart. It’s now commonplace to use mannequins, lingerie, lipstick, shoes, blood, and children’s toys as art materials, but when the CalArts group created Womanhouse, their critics read such props as evidence of a trivial concept. (Womanhouse is “as cheerful and disarming as a pack of laughing schoolgirls under a porcelain sky,” read a review in the Los Angeles Times.) Because of its insistent focus on the corporeal body, men and women found much of the work uncomfortable, even repulsive. It was a daring bit of agitprop to foreground society’s implicit disgust with the female body, but it was a gesture for which the art world wasn’t quite ready.

These factors help explain why Womanhouse is overlooked by art history, but it was the project’s association with the ill-fated theory of “core imagery” that most damaged its reputation. Core imagery was Schapiro and Chicago’s solution to the culture’s unremitting emphasis on the phallus. Their theory holds that women who are completely free to express their innermost selves will gravitate toward depicting or enjoying specific shapes: circles, enclosures, holes, gashes, hollowed boxes, ovoids—forms that mimic the specific anatomy or biology of women’s bodies. Core imagery was intended as an alternative feminine iconography, based on the figure of a penetrable vagina. (It was specifically the vagina, not the clitoris or labia, that, in Chicago’s words, expressed the “philosophical” fact of womanhood.) Schapiro and Chicago developed core imagery during their work on Womanhouse and immediately afterward; according to several students, the duo became obsessed with anything that had a hole in the middle. One student recalls, “I thought I would throw up if I saw another drawing of a split pear.”

Schapiro remembers it differently; she wrote later that Womanhouse “confront[ed] the symbolic penis with the symbolic vagina.” That spring, she and Chicago reiterated the point with a joint presentation at the inaugural Conference of Women in the Arts, at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC. In their presentation, they argued that the injury to women artists was more extensive than had been previously articulated. It was extremely difficult for a woman to be an artist, because as a woman, her work and her reputation were subject to prejudice that a man’s were not. Yet a woman artist might succeed if she was willing to disguise or excise (or, on occasion, deny) the “feminine” aspects of her work. If she refused, she had no artistic future; she could not openly express the reality of existence as a woman. In other words, women might be accepted as artists if they tacitly agreed to make work that looked like that of a man, but they remained forbidden from making work that looked like that of a woman. The problem in all this, of course, was the assumption that art by women looks like women’s art.

Even before the end of their presentation, protests began. The artist Agnes Denes shouted, “The only inner space I recognize is where my brain is—and my soul!” When Chicago said it was a relief to finally talk about menstruation with other women (in reference to Womanhouse’s Menstruation Bathroom), sculptor Lila Katzen exclaimed, “That’s your problem!” The presentation sent reverberations through the feminist-art world—a community that was just barely establishing itself. Core imagery contradicted the feminist party line, which argued that the biological differences between men and women were irrelevant, while lesbians and women of color challenged the right of two white heterosexuals to define the universal aesthetics of femininity. Women artists disavowed any interest in painting or sculpting the shapes that core imagery championed, and an emergent field of feminist critical theory argued that women were better served by criticizing than by affirming the stereotype of women as all body and no intellect.

Schapiro and Chicago assembled a chronology that demonstrated the omnipresence of vulvar forms in women’s art through time, but their evidence remained unconvincing. Many woman artists simply didn’t fit the profile, while some men did, and there were several living artists who refused it outright. Georgia O’Keeffe was a thorn in Chicago’s side. Anyone familiar with O’Keeffe’s blushing flowers can see that the painter should have been a key link in the visual etymology of core imagery, but to Chicago’s bewilderment, O’Keeffe adamantly declared herself an artist, not a woman artist, and refused Chicago permission to publish images of her work.

Schapiro and Chicago stood their ground. Their detractors lacked courage, they said, and had been brainwashed into hating their own femininity. Schapiro and Chicago drew strength from their conversations with women outside the art world, who generally had no compunctions about enjoying art by women as art by women. Within the art world, however, the theory was stripped of credibility. Even today, many women artists share an aversion to feminist art that stems in part from the fallout of the core-imagery debacle.

A generation later, the conspicuous flaw of core imagery is not the suggestion that women make different art than men—perhaps they do—but that Schapiro and Chicago’s pet theory was unnecessarily complex, a clumsy embellishment of what should have remained a straightforward assertion. The essence of Womanhouse and the raison d’être of feminist art was the simple and incontrovertible fact that women are entitled to represent their experience of the world.

Core imagery may have bungled this basic truth, but Chicago remains feminist art’s most vociferous advocate. In a letter she sent in the summer of 1973 to art critic Lucy Lippard, Chicago wrote that she was spending her summer days wearing the same sleeveless T-shirt, putting in long hours finishing a triptych of paintings in sprayed acrylic. The triptych was large, a total of fifteen feet wide and fifteen feet long, and the studio was unbearably warm. “I have actually dared to show my horrendously huge muscled arms whose biceps measure about sixteen inches,” she wrote. “For years I have hidden them in long-sleeved shirts but it is too hot for vanity and besides, what’s wrong with having big muscles, a husky, firm body and a cunt?” As in Littman’s film, the true subject of Chicago’s letter is not the art but the consciousness of the artist. Chicago’s veiled confession of vanity, her faux-casual use of the word cunt, and her awkward rhetorical phrasing suggest her own internal struggle to become a new kind of artist, one that still holds fiercely to her identity as a woman. Early feminist art may not be remembered for its artworks, but it will be remembered for its feminism—and there is every indication that Schapiro and Chicago would have judged that a success.