This is part II of an excerpt from Sebastian Deken’s book on the classic Super Nintendo role-playing game, Final Fantasy VI. To read part I, click here.

Shadow

Of the game’s protagonists, Shadow is the most laconic (excepting Gogo, the agender mimic who speaks three lines to introduce themself, then never again). He floats in and out of the party at his own discretion, sometimes only participating if he’s paid. By way of introduction, we’re told “He’d slit his mama’s throat for a nickel.” A player can start and finish the game without learning a thing about Shadow’s complicated history; nothing about it is explicit in the first half of the game. If you play your cards wrong, he’ll disappear on the Floating Continent—and you’ll never learn who he is. Shadow is more than a nameless mercenary. He’s a man on the run from himself.

His given name is Clyde. As a young man, he formed a train-robbing duo with his friend Baram. As they celebrated a particularly successful heist, they jointly adopted “Shadow” as their nom de crime. The next job went horrifyingly wrong: The two were on the run, in danger of being caught, and Baram was mortally wounded. He begged Clyde to take a knife and put him out of his misery, but Clyde was shaken by the idea and couldn’t bring himself to kill his friend. He sprinted away instead, leaving Baram to die alone, in pain, crying for mercy. The guilt still racks Shadow when the player meets him more than a decade later.

Shadow’s past bubbles up through a series of achronological, randomly occurring dreams, only viewable in the anything-goes second half of the game. These complement Relm’s, and only after seeing into both characters’ pasts can the player finally trace the line from father to daughter.

In one dream, Clyde stumbles, half-dead, into a familiar village square, where a dog finds him and fetches a young woman for help. In another, he is walking away from a familiar home—the very home Relm shares with her grandfather, Strago. His dog follows him out of town. “You came to fetch me,” Shadow says. “But I won’t be going back. I want you, and the girl, to live in a peaceful world.” He keeps the dog, but orphans his daughter quick as a knife slices.

In a final nightmare—I can’t help but think must be recurring—Baram implores Clyde to join him in death.

*

To paint Shadow through music, Uematsu pays homage to Ennio Morricone’s work, specifically from the Dollars trilogy—A Fistful of Dollars (1964), For a Few Dollars More (1965), and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966). He mashes up elements from each of these three movies’ theme songs (the omnipresent whistle, the strum of a guitar, the mouth harp) to create an instantly recognizable reference that captures Shadow’s withdrawn, prickly personality, recalling Clint Eastwood’s iconic stone-faced screen presence. He doesn’t wear a poncho and smoke cigarillos like Eastwood, but, like a stock character from old Westerns, he does have a background in train robbery. Then there’s the connection with Eastwood’s role, the Man with No Name: Shadow didn’t just adopt his name to hide his identity; in the original Japanese script of FF6, Shadow tells the other heroes, “I’m a man who threw away his name.” (Ted Woolsey translated this line for the SNES as “I’ve forsaken the world.”) Shadow wants to become no one.

A Fistful of Dollars was an unlicensed remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961), about a dark-robed ronin. This cowboy music, repurposed for a mysterious ninja, traces a line back to Kurosawa, who himself borrowed heavily from American Westerns. Uematsu acknowledges and exploits this loop of references to create a razor-sharp portrait: Within a few measures, we learn that Shadow will be enigmatic, distant, and mercenary—and that he’s capable of impressive acts of heroism.

Shadow’s special ability in battle is “Throw.” He can toss shuriken, knives, and short swords at enemies to cause massive amounts of damage. This talent makes sense for a ninja, but also for Shadow’s character: He can throw items away in battle, including the game’s most powerful and priceless weapons. He threw his partner, his daughter, and his name away. One way or another, he throws himself away. His “Throw” allows him to keep as cool a distance from his targets as he keeps from the other heroes, and it acquits him of delivering a fatal wound face to face.

Unexpectedly, Shadow performs several acts of generosity and self-sacrifice. When prodded, he offers taut advice on love and grief to other characters. He helps the martial artist Sabin, a total stranger, infiltrate the Imperial base at Doma. He (usually) sticks with Sabin and Cyan to board, and escape from, the Phantom Train—a terrifying, sentient manifestation of death (and an unsubtle callback to Shadow’s past). On the Floating Continent, he saves a life—that of Celes, the former Imperial general and onetime soprano. Then he stays behind to stymie Kefka so the other heroes can get away safely.

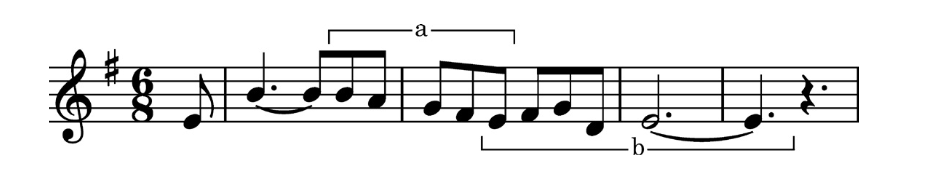

Shadow and Relm are pretty different: Relm is “forests, water, light,” and her father is a shade who “comes and goes like the wind.” Light opposite dark. Wind through the trees and over the water. They are different but entangled. The up-and-down eighth notes in the father’s music have the same nose as those in the daughter’s (figure 3.4), but the overall resemblance is thin—different rhythms, different placement, different dispositions. The F-sharp major key of Relm’s theme is just a step away from Shadow’s E minor—very close—but the keys have no real relationship with each other outside their proximity. Shadow and Relm come so close to each other in-game—they can explore together and fight together, if the player wants them to, and when they are idle they hang out with the rest of the crew belowdecks in an airship. But they never speak or interact. Related, but never relating.

During the escape from the Floating Continent, you have a choice: You can make the heroes jump to their airship as quickly as possible, leaving Shadow behind to die, or you can risk it and wait for him before you take the leap—he catches up mere seconds before the fall. The choice is brutal: On the first playthrough, you don’t know what will happen if that countdown clock reaches zero. Will Shadow show up? Will the heroes die waiting for him? If they die, will you have to hack your way through the punishing Floating Continent stage again? If Shadow is left behind, will he find his own way to survive? The cruelty of this choice mirrors the awful choice that Clyde had to make about Baram: Will you risk yourself, shaking with anxiety, for mercy on your friend—or will you cut and run?

The choice is real: Shadow will disappear from the game if the player doesn’t wait. I didn’t wait when I first played through, and I felt his disappearance in my gut for the rest of the game. I hoped to find him somewhere in the ruined world, but all I found was a ghost in my roster and a conspicuous absence during the game’s curtain call. It haunted me, in its own little way.

If he lives through to the final battle, Shadow confesses to Kefka that he finally understands friendship and family. That’s why he chooses to fight. But after Kefka is defeated, as his tower is collapsing, there’s no more fighting to be done. His last big job, as professed in his dream—to leave his daughter Relm in a peaceful world—is complete.

And so Shadow goes on the lam for the last time, lagging slightly behind his comrades, then nestling himself unnoticed in a corner. He knows his death will go unacknowledged and unseen, just as his suffering friend’s did. “Baram! I’m going to stop running. I’m going to begin all over again…”

Shadow’s theme, like all the other heroes’, is recalled in the endgame medley. It plays during his final moments—not just his final moments on screen, but his final moments of life. Instead of a whistle, the melody is played by the strings; instead of a strummed guitar, cascading arpeggios on the harp; instead of the twang of a mouth harp, the cry of French horns. The lonely stoicism of the Morriconesque theme is split at the sternum, exposing a raw, beating heart. Unlike the silent cowboys who precede him, who may stride coolly offscreen, Shadow faces his demons. Perhaps it’s because of this reckoning that he chooses to die—a rare, tragic denouement of clenched-jaw masculinity.

Uematsu has crafted a tremendously elastic melody, stretching effortlessly from tumbleweeds to chrysanthemums. That Western-movie sound is a pinpoint-specific pop-culture reference, a treatment none of the other characters’ themes receive. Yet it transforms in the ending medley, shedding its roots to blend in seamlessly with the other characters’ themes. The music’s stoicism melts away to convey grief, guilt, compassion, and resolve in one quick jab. Shadow, himself a pop-culture trope, becomes more like his comrades and less like Clint Eastwood as he gains a name, a past, and a heart. What remarkable sleight-of-hand to turn such worn material—a strong-but-silent warrior, the music of dust-beaten men drawing their pistols—into something so gut-wrenching and complicated. If you take the time to look closely—and both he and the game work hard at making inspection difficult—you see that Shadow wears twenty different shades of black.

Landscapes

Uematsu’s musical landscapes are as evocative as his portraits: full of whip-smart choices and references that reinforce what’s onscreen and telegraph what isn’t. There’s the coal-mining town Narshe’s jazzy looseness, now and then sounding a quick-exhaled breath as a kind of soft percussion—the soft puffs of steam we make when we breathe out in the cold. Machinery onscreen here and there emits its own steam, and Narshe’s coal powers the game-world’s steam engines. The loose harmonies hint at Narshe’s uneasy neutrality in the war, the underground operation of the resistance, the constant threat of invasion.

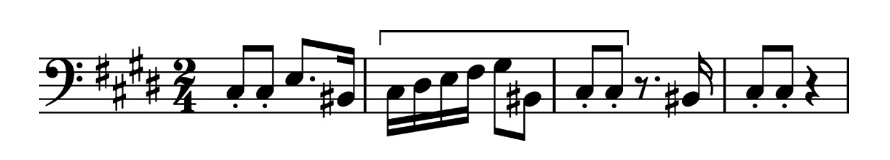

The Magitek Factory’s theme, “Devil’s Lab,” also gives an immediate sense of place. Uematsu’s use of synthesizers to indicate artificiality and evil, and to hint that a confrontation with Kefka is on the horizon, is front-and-center. The piece begins with a steady beat of industrial sound effects—mechanical clicks and anvil-like clangs—then a killer bass-synth riff (figure 3.5). It may be the stankiest groove in video game music history, rolling and locking like someone doing the robot. Robot is pretty much the idea—together, the bass and percussion create a conveyor belt–like motion that rolls the rest of the music steadily forward. Whooshes and buzzing alto synths, like beeps of a computer and swings of a mechanical arm, accent the music’s brass melody. A string section wanders in, looking up and down, mesmerized, watching it all as if through a window. Onscreen are actual conveyor belts, crane-arms, and ducts. Everything is riveted steel. It’s a grinning Trent Reznor cameo, or a funk that transforms the whole scene into the music video of Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation.”

It’s so much fun, in fact, that one might forget how sinister a place this is. The ducts and conveyor belts and steel are built on the backs of living beings. Espers are kept in glass tubes like captured beetles—their life is drained and their exhausted bodies are dumped into garbage pits. The laboratory part of “Devil’s Lab” is clear from the first measure of music; the devil reveals itself only slowly.

Then there’s the distinguishing sounds of the World of Balance and the World of Ruin. The overworld themes’ contrast is the starkest: Terra’s grassy theme music, which plays during exploration of the World of Balance, is replaced by “Dark World”—a dour, plodding number for pipe organ, clavichord, tubular bell, and whistling wind. Where the land had been spring green and deep blue, it’s now dun plains with bruise-purple waters. The World of Balance’s pan flute is sounded by human breath; the World of Ruin’s organ bleakly sucks in the air from its surroundings.

In the World of Balance, free towns are scored by “Kids Run Through the City,” a pastoral piece in a triple meter, cradled by a flute, acoustic guitar, and strings. Ruin towns have the utterly cheerless “The Day After.” This one is still fronted by a flute, but this time with a wailing oboe and weeping mandolin. It sounds like a reject from the Godfather soundtrack, and calls to mind New York’s early 20th-century Italian ghettos. The town’s maps haven’t changed, but their music has. And their colors—like their spirits—have dimmed considerably.

In one last grand contrast, the World of Balance’s airship music sounds like a Showcase Showdown on The Price is Right—you’ve just won a five-day, four-night stay at a resort in sunny Bali!—where Ruin’s is the cold, wispy opening of a dour soap opera.

Rather than simply recycling music from the first half of the game to the second, as some composers might, Uematsu reinvented. This is part of the ingenuity of the game’s soundtrack. It resists sameness in ways many of its contemporaries and predecessors didn’t; and that specificity breathes a unique life into each environment. “Devil’s Lab” is only heard one time in the game, and then it disappears forever: You can’t go back to the Magitek Factory after your first visit because you blow it up on your way out. Because of the music’s singularity, though—and its funky bassline—the factory looms large in the player’s memory long after it’s gone.

The Phantom Train

The Phantom Train delivers souls from the material world to the afterlife. Early in the game, you accidentally board it while it’s parked at its platform in the Phantom Forest, then you must find a way to get off the train before it reaches the afterlife. Only when the train delivers you back to your origin in the woods do you see how grim it truly is: You are forced to watch the murdered people of Doma slowly file aboard.

Your time on the train is set to the tune of an almost-but-not-quite jazzy minor-key waltz, jump started by some ambient train sound effects. Ballroom music feels appropriate for the train’s Belle Époque–styled cars, but the harmonies are a little twisted, and though it’s technically a quick vivace—about 163 beats per minute—it feels like a ponderous largo. In the complete absence of living beings, there are no dancers to track across the floor and no way to know if this waltz should feel quick or lumbering. The lives of the souls on this train—were they too fast or too slow? That the music is forced to loop over and over again does nothing to lessen its inexorability. As the train’s ghosts so aptly put it: “N.o…e.s.c.a.p.e…!”

Dance music, in this context, nods toward the danse macabre, the idea that we are all dancing toward certain doom. Camille Saint-Saëns’s famous Danse macabre (1874) is probably the most well-known musical rendering of this idea, and it also has a distinctly waltzy meter and melody. But “Phantom Train” is closer in spirit to one of Shostakovich’s “jazz” waltzes—which, though they do sound a bit spooky to the modern ear, are not explicitly death-related.

The Phantom Train is an insistent memento mori—a tangible reminder that we’re all gonna die: A train, after all, travels in only one direction, and on a predetermined, unchangeable course. That the characters accidentally trap themselves onboard is another bony elbow to the chest. Bodiless, white-robed ghosts wisp to and fro over the red and gold carpet, and their presence does nothing to lessen your disquietude. Some volunteer to fight alongside you temporarily, some try to kill you, and some peddle basic provisions—commerce is certain even in the great beyond.

To escape the train, Sabin, Shadow, and Cyan must destroy the engine car in a battle—but in order to fight it, they have to get in front of it: The boss fight takes place with the trio running ahead of the engine car, on the tracks, turning around to strike it when they can. Three people trying to outrun and destroy an unstoppable steam-engine Grim Reaper: Has any video game ever mementoed so much mori?

Sabin, with his extensive training in the martial arts, is famously capable of performing a suplex on the train’s engine car, whisking it up in the air and crashing it back down onto the ground. I doubt that, when the developers programmed Sabin’s special abilities, they envisioned him body-slamming a hundred-ton personification of death, but it’s certainly the most fun thing to do with that skill. For that brief moment in the sky, death is suspended, and you and Sabin are invincible, everlasting.

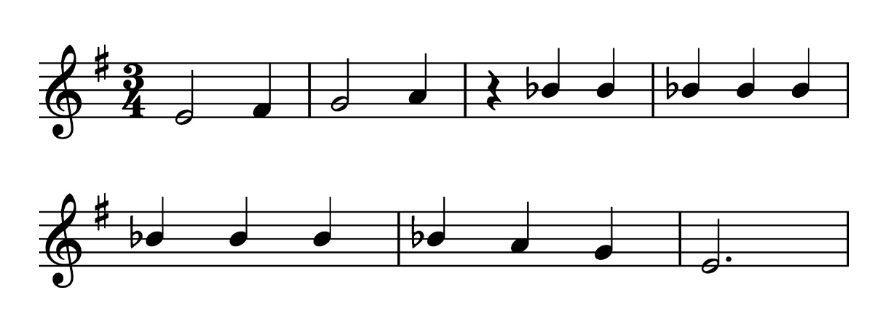

The train’s music mirrors the journey through the train itself. It begins with a gentle guitar prelude (becoming an interlude after the first loop), then surprises with a shockingly loud brass melody: sudden death! The first phrase of the melody is an unbroken line in the brass. The second phrase is split in two, ending in a pattern of twelve notes—the stroke of midnight, perhaps—broken away from the rest of the phrase by a quarter rest. The pattern holds steady on a B-flat for nine of the twelve strokes, then drives suggestively downward into an E (figure 3.6). The B-flat pitch itself is significant—it’s a tritone away from the tonic E, the piece’s central pitch. In European classical music, the tritone interval is known as diabolus in musica, or “the devil in music,” because of its dissonant quality. It isn’t very easy on the ears. The tritone is associated with death and evil—Saint-Saëns’s Danse macabre also plays with the interval. Uematsu is really hammering this theme home.

After two statements of the primary melody, the strings wail through a hysterical descending passage. They’re interrupted by a two-note blare from the brass— then they repeat their complaint note for note. Are the strings falling into the grave? Or are they trying to claw their way out of it, stomped back down by the trumpets? Who’s piling the dirt on top?

Despite their resistance, the strings must yield to the quiet strum of the guitar, and the cycle must begin again, then again, then again. It’s cartoonish, over-the-top morbidity. Think of “The Skeleton Dance,” Disney’s 1929 cartoon short, in which skeletons skip about and do the Charleston in lo-fi black-and-white. For economy, lots of the animation in the short is seen again, then again, then again—just as, for function, the music in this game must loop. But the looping feels almost intentional here: For the roughly thirty minutes of time the player spends on the Phantom Train, the music drills again, then again, then again. It is always present, always plodding forward. It might be diverted temporarily by battle sequences, but until we figure out how to body-slam Death, it will return to claim us—again, then again, then again.

Though Final Fantasy VI can be wacky, it doesn’t make a joke out of grief. Even the near-comic absurdity of the Phantom Train disappears in the face of genuine loss. The game’s cast is large and diverse, but they are united by trauma—if not the loss of loved ones, then the loss of the world as they know it. They all cope in different ways: through nightmares, visions, obsession, withdrawal, found family, and arts and crafts. They also rise against their grief—or because of it—to fight for what they believe in.

This sequence on the ghost train is more than a whimsical spook. Consider Shadow: He is a former train robber whose partner’s death is an open wound. What does this journey mean for him? He doesn’t utter a word about it—but his presence doesn’t feel like an accident.

More important is what this moment means for Cyan, who sees his wife and child boarding the train and is offered one last, torturous chance to say goodbye. After the train departs, Cyan stands at the end of the platform, just in front of the clocktower, staring quietly downward.

As Sabin, the player paces up and down the platform, anxious to move on to the next part of the game. But no matter how hard Sabin prods, Cyan won’t utter a word. Shadow asks you to shut up and keep still. As is the game’s apocalypse, this is one of few completely soundless moments, and for good reason. The silence weighs heavier here than any music could.

Sebastian Deken’s book on Final Fantasy VI is available for purchase via Boss Fight Books.