The letters arrived in the winter of 1827 at Mr. Foster’s shop on Leadenhall Street, dozens of them written in the careful quill-scratches of women from across London. Outside the wax seals bore the usual array of signets and intricate floral patterns; inside they concealed the usual bouquet of lavender fragrance, of banal sentiment, of coy subterfuge, of naked honesty.

There were those that immediately cut to the matter at hand: “I propose meeting you tomorrow at twelve o’clock,” summoned one, “I shall be… distinguished by wearing a black gown, with a scarlet shawl, white handkerchief in my hand.” In another, a twenty-two-year-old orphan wasted no time. “You will favor me by calling to-morrow November 30th, between the hours of four and five,” she commanded. “Be punctual…”

But he was not punctual.

There were those, as always, who insisted they’d never done this before: “Now, I am not generally disposed to view advertisements of this description in a very favourable light, but…” one started. Some refused to describe themselves at all—“I say nothing of my personal appearance, as I propose ocular demonstration”—while others trustingly revealed themselves to him. “I am considered a pretty little figure,” wrote one. “Hair nut-brown, blue eyes, not generally considered plain, my age nearly twenty-five.”

But he did not care how they looked.

Others tried banter. “Although your advertisement reads very fair,” one teased, “there may be some little trick on your side.” Another poked at him that “I beg to answer your advertisement of last Sunday, but really think it nothing but a frolic…” Others, less confident, fumbled through misspellings and plainly bared their own desperation to him. “I think Providence as ordained that you and I shood come together,” an eighteen-year-old wrote hopefully, “for I am not very pleacntury situated myself…”

Words, words, words. It didn’t matter. They’d wait for him, he wouldn’t show up, and they’d walk home through the streets of London alone and disappointed—How? How could I be so stupid?—seared by having foolishly trusted their hopes to an unknown man.

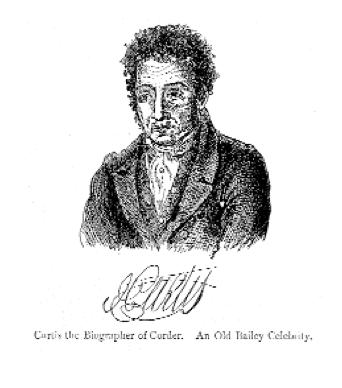

The letters made for piteous reading, if only someone would read them. But Mr. Foster didn’t care: it wasn’t his job to care. They weren’t his letters. The missives arriving in his stationer’s shop were for a boarder who lived down the street, a supercilious young man who had advertised for matrimony in the Times under no name at all, save for two initials: A.Z. A day passed, then a week, then months, and soon Foster hardly noticed A.Z.’s pile of unopened letters. He was too busy selling his wares to...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in